The other duets given at Lincoln’s Inn Fields this season were:

French Peasant

Passacaille

French Sailor and his Wife

Shepherd and Shepherdess

Spanish Entry

Le Marrie

Two Pierrots

Running Footman’s Dance

Fingalian Dance

Burgomaster and his Frow

Tollet’s Ground

Chacone

Venetian Dance

Swedish Dance

Spinning Wheel Dance

The last two duets were performed only during the summer season.

It is immediately apparent that Lincoln’s Inn Fields offered a wider range of entr’acte choreographies than Drury Lane in 1725-1726. This was related to the dancers employed there this season, as well as John Rich’s habitual use of dance as a weapon in his rivalry with the other patent theatre.

The French Peasant danced by Nivelon and Mrs Laguerre on 29 September 1725 was one of the perennially popular dances on the London stage. So far as I can tell, a French Peasant duet was first advertised at Drury Lane on 15 June 1704, when the dancers were Mr and Mrs Du Ruel. It would continue in the entr’acte repertoire until the early 1740s. Several Peasant or ‘Paysan’ dances were recorded in notation in the early 1700s, including this choreography by Guillaume-Louis Pecour published in the Nouveau recüeil de dance de bal et celle de ballet around 1713.

These dances may provide hints towards the French Peasant dances on the London stage.

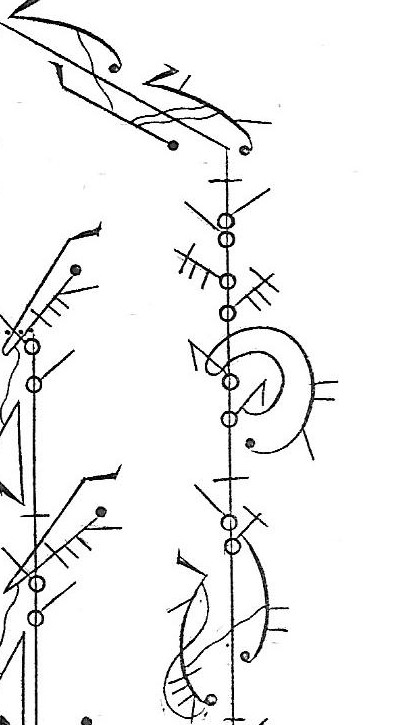

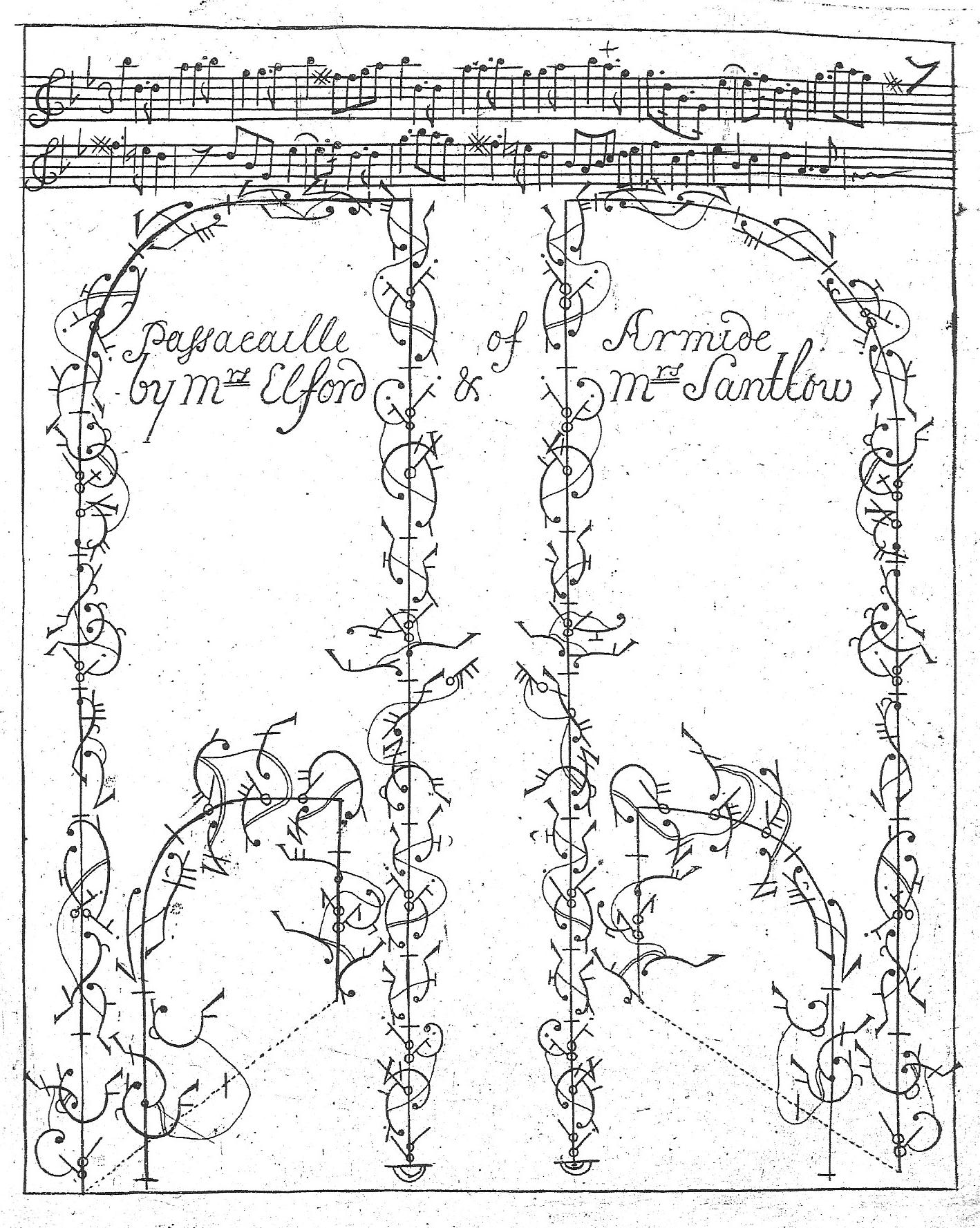

The Passacaille was seldom advertised as a duet in London’s theatres and the two performances given at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 13 October and 9 November 1725 by Lally and Mrs Wall seem to be the last to be billed before the 1770s. The only notated passacaille duet for a man and a woman, choreographed by Guillaume-Louis Pecour for Ballon and Mlle Subligny, was published in 1704 and thus does not necessarily provide an exemplar for a dance of the mid-1720s. I wrote about both solo and duet passacailles in my post The Passacaille back in 2017.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, ‘Sailor’ dances on the London stage go back to the 17th century and were a frequent feature in 18th-century entr’acte entertainments. A French Sailor duet was performed at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in the mid-1710s, but the French Sailor and his Wife performed there on 25 October 1725 by Francis and Marie Sallé seems to mark a new chapter in the stage life of the dance. I can certainly devote a post to the sailor dances in London’s theatres, so I won’t pursue the topic further here. It is just worth mentioning that a Matelot duet was introduced to the entr’actes at Drury Lane in 1726-1727, raising a question about the difference between it and the French Sailor dances.

I discussed Shepherd and Shepherdess dances in an earlier post, Season of 1725-1726: Entr’acte Dances at Drury Lane and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, so I will move straight on to the Spanish Entry given as a duet by Lesac and Miss La Tour on 2 November 1725. I have written about ‘Spanish’ dances before – in posts entitled ‘Spanish’ Dances, Dancing ‘Spaniards’ and ‘Spanish’ Dancing and the Dance Treatises – but I haven’t taken an extended look at such dances on the London stage. I am not going to attempt that here, although it is certainly another topic worth exploring. There were Spanish Dances and Spanish Entries advertised in the entr’actes at London’s theatres from the first decade of the 18th century, which probably drew on similar choreographies from the Restoration period. The Spanish Entry had been advertised as a duet at Lincoln’s Inn Fields and had stayed in the repertoire for a few seasons. It had then disappeared, only to reappear in the mid-1720s with the duet danced by Lesac and Miss La Tour. The use of the word ‘Entry’ for this dance suggests (to me at least) that it was less likely to have been a version of the Folies d’Espagne than one of the other dance types made popular in the French comédies-ballets and opéra-ballets given in Paris. Here is the first plate from Pecour’s well-known ‘Entrée Espagnolle’ for Ballon and Mlle Subligny, which provides one example that may have been influential (it was transcribed by Kellom Tomlinson in his ‘WorkBook’ compiled during the first two decades of the 18th century).

‘Le Marrie’ danced by Francis and Marie Sallé at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 16 December 1725 must surely have been Pecour’s ball dance La Mariée, first published by Feuillet in his 1700 Recüeil de dances composées par Mr. Pecour. As I wrote in another post back in 2015, La Mariée on the London Stage, research by the American dance historian Rebecca Harris-Warrick has shown that this duet probably began as a stage dance in Paris and reached the London stage shortly after 1698. The Marie performed at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1717-1718 could have been La Mariée resurfacing in the entr’actes, although its performance by the Sallés seems to have given the duet a new lease of life with regular revivals at benefit performances. Here is the first plate from the 1700 collection.

Two Pierrots was also danced by the Sallés at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 16 December 1725. They seem to have introduced the male-female duet to London – previously there had been a few Pierrot solos and an all-male duet by Francis and Louis Nivelon in 1723-1724. The Sallés were answered at Drury Lane by Roger and Mrs Brett in La Pierette later that season. I should probably have counted Two Pierrots and La Pierette among the entr’acte dances shared between the two theatres, although the titles suggest that two might have been quite different thematically if not choreographically. Pierrot dances would last into the 1750s and beyond.

The Running Footman, danced by Nivelon and Mrs Laguerre on 10 March 1726, had been introduced to the London stage by them in 1723-1724. It was probably created by Nivelon and I looked at the duet in some detail in my post Dances on the London Stage: The Running Footman back in September.

The Fingalian Dance performed by Newhouse and Mrs Ogden on 11 April 1726 had first been danced by them in 1724-1725. They would continue to perform it regularly each season until 1733-1734. This entr’acte duet had apparently begun life as ‘A new Irish Dance in Fingalian Habits by Newhouse, Pelling, and Mrs Ogden’ at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1723-1724 but the trio format did not survive the season. Newhouse and Mrs Ogden were also billed more than a dozen times during 1724-1725 in an Irish Dance. I think that was probably the Fingalian Dance, which I am guessing was choreographed by Newhouse. There are a number of ‘Irish’ tunes in the various editions of Playford’s The Dancing Master, all considerably earlier than the duet by Newhouse and Mrs Ogden. They may hint at the music for the Fingalian Dance, although the dance itself seems to have been characterised by its costumes as much as the ‘Irishness’ of its music. Fingal is a county in Ireland in the Dublin region – the reference to ‘Fingalian Habits’ suggests costumes that are at least recognisably Irish. So far, I have not managed to find any clues as to what these ‘Habits’ may have been like. Fingalian Dances would survive in the London stage entr’acte repertoire until the 1770s.

The Burgomaster and his Frow, another entr’acte dance performed by Newhouse and Mrs Ogden on 20 April 1726, was one of the many ‘Dutch’ dances given in the entr’actes at London’s theatres. The duet seems to have been variously titled – as Dutch Boor in 1723-1724 and 1724-1725 and as Dutch Burgomaster and Wife in 1724-1725 – but it seems to have been distinct from the Dutch Skipper, which Newhouse was never billed as dancing. There is, of course, music for a ‘Dance for the Dutch man and his Wife’ in Thomas Bray’s 1699 collection Country Dances. This tune was used in Europe’s Revels for the Peace, the masque created to celebrate the peace of Ryswick that ended the Nine Years’ War in 1697.

Tollett’s Ground, danced by Newhouse and Mrs Laguerre on 30 April 1726 and revived during the Lincoln’s Inn Fields summer season by him and Mrs Ogden, took its title from its music. The piece is generally attributed to the Irish musician Thomas Tollett, who worked in London’s theatres during the 1690s and may have died in 1696. It appeared in several music collections around 1700 and was first billed at Drury Lane in 1701-1702, when it was performed by John Essex and Mrs Lucas. During the 1710s it was given several times by Margaret Bicknell and her sister Elizabeth Younger. The Tollett’s Ground duet survived into the early 1730s and was usually performed at benefits or during the summer season.

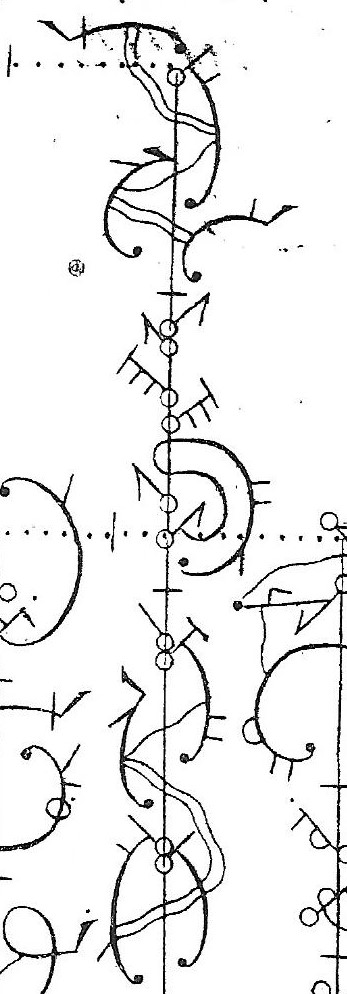

I mentioned the Chacone in my post The Most Popular Entr’acte Dances on the London Stage, 1700-1760 a couple of months ago. In 1725-1726, a Chacone duet was danced at Lincoln’s Inn Fields by Dupré and Mrs Wall on 30 April and then 23 May 1726, followed by Lally and Mrs Wall on 30 May. Some of the chaconnes given in London’s theatres were associated with Harlequin, but others (including this one) were evidently serious dances. We do have a local notated example of a chaconne for the stage which was published around this time and might shed light on some of those given in the entr’actes. Anthony L’Abbé choreographed the ‘Chacone of Galathee’ for Delagarde and Mrs Santlow (from 1719 Mrs Booth) perhaps around 1712, although it seems to have been notated some ten years later – around the time it was published by Le Roussau in A New Collection of Dances. As this plate reveals, it was a showpiece of virtuosity for these two dancers (I strongly suspect that Delagarde’s entre-chat à six should also have a tour-en-l’air, and I certainly think that Mrs Santlow was capable of adding an entre-chat à six to her tour).

The Chacone duets danced by Dupré and Lally with Mrs Wall in 1725-1726 may have been similar.

The Venetian Dance was given just once this season, on 9 May 1726 by Burny and Mrs Anderson ‘both Scholars to Essex’. At present, I can’t be sure whether ‘Essex’ is William Essex, who had made his debut at Drury Lane the previous season, or his father John, who had left the stage to pursue his career as a dancing master more than twenty years earlier. John Essex is perhaps the more likely candidate. It is tempting to assume that a Venetian Dance must be performed to a forlana, but a contemporary source suggests a quite different piece of music – the allemande used by Pecour for his duet of that title, published in Paris in 1702. I have puzzled over this musical choice, apparently made for a ‘Venetian Dance by Mr Shaw and Mrs Booth’ which was performed (but not mentioned in the bills) in 1724-1725. I can see that I should return to Venetian Dances in another post.

Dances associated with particular nations were decidedly popular at Lincoln’s Inn Fields this season. Another was the Swedish Dal Carl given by Pelling and Mrs Ogden on 17 June 1726 (the opening performance of the summer season). A ‘new Swedish Dance’ had entered the entr’acte repertoire at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1714-1715, when it was performed by Delagarde and Miss Russell (later Mrs Bullock and a leading dancer at that theatre). Thereafter the Swedish Dale Karl, as it was usually known, was performed most seasons into the 1730s. It may well have continued to use the music recorded in The Ladys Banquet 3d Book, a collection first published around 1720, although the earliest surviving edition has been dated around 1732. The ‘new Play House’ mentioned on the score is probably Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which opened in 1714. There are no solo Swedish Dances billed in London’s theatres, so is the ‘Sweedish Woman’s Dance’ actually part of the duet?

The last of the dances I listed at the beginning of this post was also performed only during the Lincoln’s Inn Fields summer season. Newhouse and Mrs Ogden performed the Spinning Wheel Dance on 21 June 1726. The duet had first been given in 1723-1724 at the same theatre and the bills indicate that it only ever received a handful of performances. I would characterise it as one of the novelty dances that turn up in the entr’actes from time to time, particularly during summer seasons.

My next post on the season of 1725-1726 will be concerned with the entr’acte solos given at Drury Lane and Lincoln’s Inn Fields.