The Britannia is the last of the six dances named on the title page of A Collection of Ball-Dances perform’d at Court. It must have been the latest of these choreographies to be created, for the dance was first performed at the celebrations for Queen Anne’s birthday on 5 February 1706. Could it have been the first dance to be published in Beauchamp-Feuillet notation in London? It is engraved in a very different style to the other dances in this collection, as the following images show, and there is evidence to suggest that it may have been published separately before A Collection of Ball-Dances appeared.

The report of the birthday celebrations in the Post Boy, 5-7 February 1706, makes no mention of a dance by Isaac, although it does say ‘At Night there was a fine Ball, and a Play acted at Court’. In his Roscius Anglicanus of 1708, John Downes adds that Edward Ravenscroft’s The Anatomist was the play ‘there being an Additional Entertainment in’t of the best Singers and Dancers, Foreign and English’. Downes names the dancers as ‘Monsieur L’Abbe; Mr Ruel; Monsieur Cherrier; Mrs Elford; Miss Campion; Mrs Ruel and Devonshire Girl’. The ‘Additional Entertainment’ may have been a musical piece, England’s Glory composed by James Kremberg, inserted into The Anatomist in place of The Loves of Mars and Venus (which had been given with the play at its first performance in 1696). This provided plenty of opportunities for dancing and had Britannia as a central figure. Isaac’s The Britannia was likely to have been danced at the ball and, given the elaborate choreography and probably short rehearsal time, may well have been performed by two of the professional dancers – perhaps L’Abbé and Mrs Elford or Mr and Mrs Ruel (L’Abbé and Du Ruel were both French, while Mrs Elford and Mrs Du Ruel were English).

The publication of the music for The Britannia was advertised by John Walsh in the Post Man for 9-12 February 1706. No such record has been found for the publication of the dance itself in notation, although May 1706 has been suggested as a possible date for its appearance. The Daily Courant for 23 April 1706 advertised that ‘This Day is publish’d’ Orchesography (Weaver’s translation of Feuillet’s Choregraphie), while the Post Man for 7-9 May 1706 similarly advertised Weaver’s A Treatise of Time and Cadence in Dancing (his translation of the ‘Traité de la Cadance’ in the 1704 Recueil of Pecour’s ‘meillieures Entrées de Ballet’). The May advertisement refers to Orchesography but says nothing about the collection of Isaac’s ball dances. However, the Daily Courant for 25 June 1706 advertised it for publication ‘Next Week’ as the ‘Second Part’ of Orchesography – apparently after the separate publication in notation of The Britannia.

Could The Britannia have appeared as early as February 1706? Isaac’s dance for 1707, The Union, was advertised as published in notation on 6 February 1707 the Queen’s actual birthday. A copy of The Union now in the Euing Music Library of Glasgow University has an ‘Epistle Dedicatory’ from John Weaver to Mr Isaac bound with it but plainly not belonging to it. Weaver writes that Mr Isaac ‘encouraged my attempt [at dance notation] & in the following Dance has furnish’d me with the first Example that England has seen’. Towards the end of his ‘Epistle’, he adds:

‘Since therefore our Part of the World derives this first Essay from your Performance & Direction tis but just in me to let the World know it & to offer this first Fruit of my Labours to you by whose Encouragement I hope Success to my farther Endeavours, the effect of which I shall speedily give the World in a Treatise of Dancing; as also an Explanation of this Art, with a Collection of all the Dances perform’d at the Balls at Court, compos’d by you & now taught by the Masters throughout the Kingdom, all which I am preparing for the Press.’

Weaver makes no reference to the dance being a ‘royal’ choreography but perhaps he did not need to, for the now lost title page (perhaps with other preliminaries) would have said enough. The title The Britannia was, of course, in itself a fulsome compliment to the Queen.

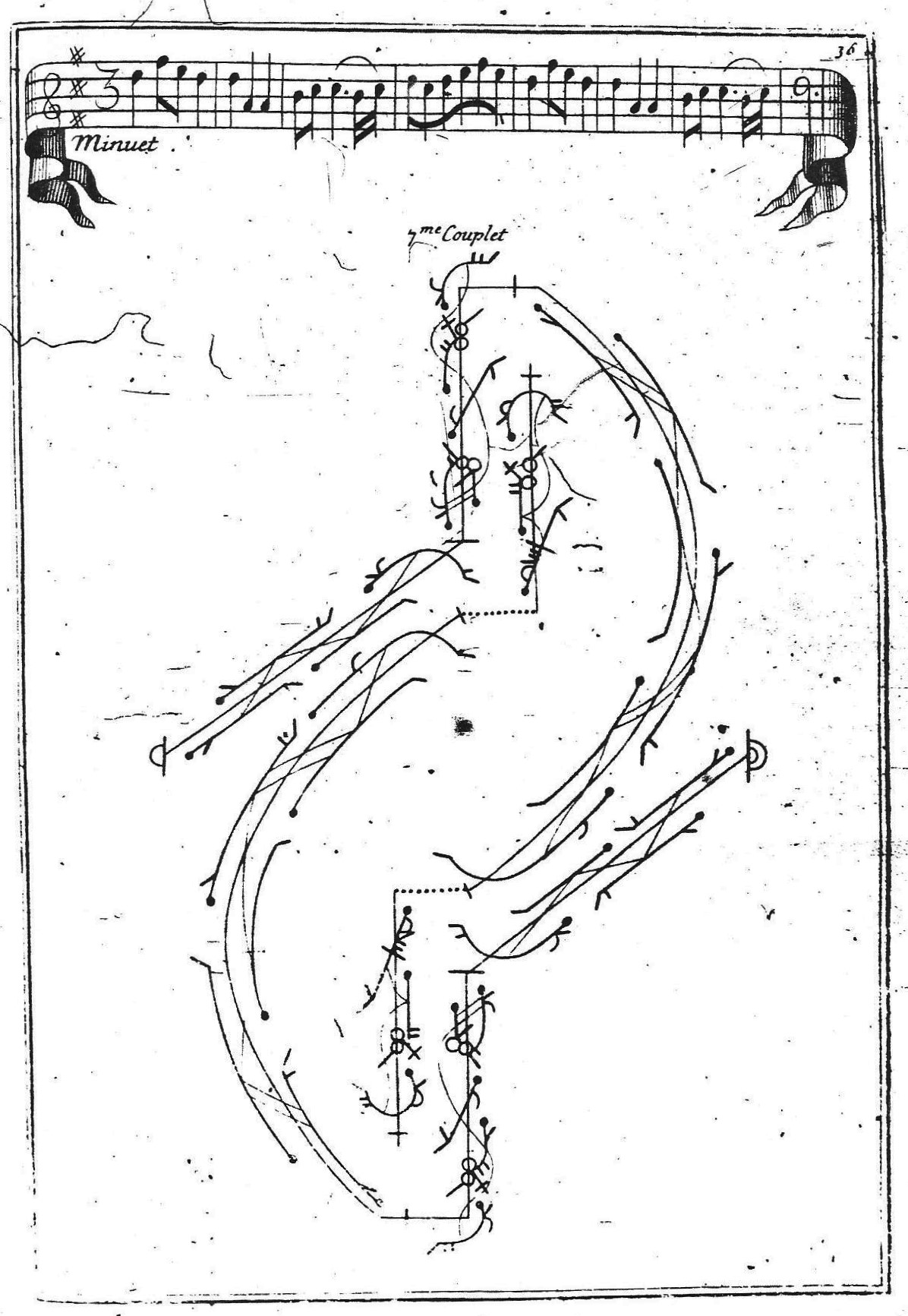

I have recently been learning The Britannia, as best I can as I work alone on these dances, and I have very much enjoyed trying to master the complexities of its choreography. As I have said before, Isaac’s compositions are very different to those of his contemporary Guillaume-Louis Pecour – even though the two men may well have had a shared early training in la belle danse. The Britannia has three sections: the opening is in triple time, with a musical structure AA (A=10); this is followed by a bourrée, also AA (A=14); and a concluding minuet which is a musical rondeau AABACAA barred in 3 (A=B=C=8). The dance has 104 bars of music in all. I have written about it previously in four posts, listed at the end of this piece. The choreography exhibits to the full Isaac’s complex ornamentations, his favourite pas composés (many of his own creation), his teasing use of figures and orientations and, of course, his customary wit and liveliness.

The couple begin the dance facing the presence but immediately turn to face each other and then make a half-turn to face away. They begin their passage downstage facing each other again and moving sideways. The bourrée section begins (on plate 3) with them facing the presence (they are still ‘proper’) and then travelling forwards and away from each other on a diagonal, before completing a half-circle to face each other across the dancing space (or perhaps not, the notation shows the woman in that position while the man apparently faces upstage. The omission of a quarter-turn sign on his ensuing contretemps is surely a mistake).

The minuet begins with the couple facing each other across the dancing space (again ‘proper’) before travelling diagonally towards the centre line but away from each other (the woman upstage and the man downstage) with a pas de menuet à trois mouvements. They then dance a variation on the contretemps du menuet on a right line away from each other. The figure seems to be an inversion of one used in the bourrée, where they travel towards one another. Here are both versions.

I have already written about the minuet to The Britannia, but it is worth mentioning again the closing figures in which the couple take both hands, finish their half-circle facing each other and then do a quarter-turn pirouette to face the presence before making a half turn to perform a jetté upstage. They do not turn back to the presence until their very last coupé.

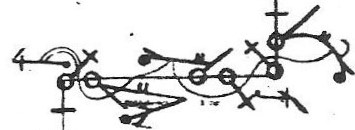

In this dance, Isaac seizes the opportunity to repeat steps (with some variation) within the different sections. There are the paired jettés-chassés in the opening triple-time section, the bourrée and the minuet, which can be found on plates 1, 5 and 8 of the notation. Here is the example from plate 1.

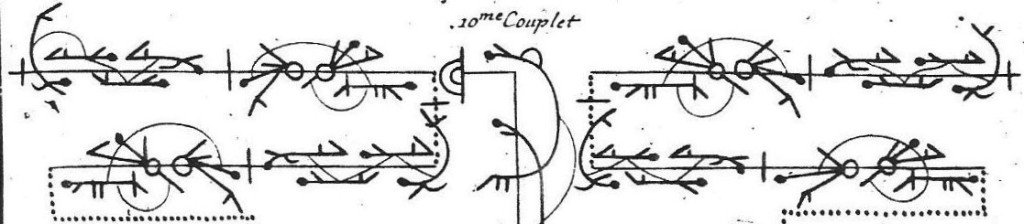

There is the pas de bourrée emboîté to plié with a hop in the bourrée, incorporated into a variation on the contretemps du menuet in the minuet (and used twice in both cases), which can be found on plates 4, 6, 7 and 12 of the notation. Here is the example from plate 4 (the bourrée, on the left) and from plate 7 (the minuet, on the right).

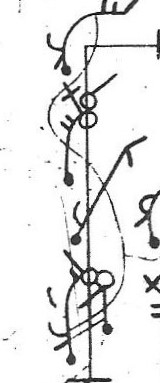

One of the aspects that make Isaac’s duets so demanding but still fun to dance is his rhythmic variety. There is one sequence in the C section of the minuet that always makes me smile. It has a hop followed by a coupé battu in the first two bars and then four demi-coupés in the second two. This little motif is then repeated on the other foot. The dancers face one another, then do a quarter-turn to travel sideways towards each other on a diametrical line, before turning their backs and repeating the whole sequence in the opposite direction. Here it is.

You will observe that, although this is a minuet, the couple are on opposite feet in mirror symmetry.

The Britannia, even more than Isaac’s other dances, raises questions about dancing at the English court in the years around 1700. The title of the duet and the occasion of its first performance suggest formality and seriousness, if not grandeur, the choreography delivers something quite different.

Previous posts:

Mr Isaac’s Six Dances

Mr Isaac’s Choreography: The Six Dances – Opening and Closing Figures

Mr Isaac’s Choreography: The Six Dances – Motifs and Steps

Mr Isaac’s Minuets

References:

Olive Baldwin and Thelma Wilson. ‘England’s Glory and the Celebrations at Court for Queen Anne’s Birthday in 1706’, Theatre Notebook, 62.1 (2008), 7-19.

John Downes. Roscius Anglicanus, ed. Judith Milhous and Robert D. Hume (London, 1987), p. 98.

Meredith Ellis Little, Carol G. Marsh La Danse Noble: an Inventory of dances and Sources (Williamstown, 1992), [1707]-Unn.

William C. Smith. A Bibliography of the Musical Works Published by John Walsh during the Years 1695-1720 (London, 1968), nos. 196, 207.