It is quite some time since I have explored dancing in one of the seasons on the London stage, and quite a while since I have been able to publish a post on Dance in History as I have been busy with other research and writing. Nearly three years ago, I posted Season of Dancing: 1716-1717 to try to place in context the first performances of John Weaver’s The Loves of Mars and Venus. I have been thinking about Weaver and his work over the past year and more, so I thought I would look back a little further to see what was happening on the London stage in the preceding seasons and what light that might shed on Weaver’s ground-breaking ballet. The starting point of 1714-1715 is, of course, determined by the opening of the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre that season and the return to theatrical competition for the first time since 1710-1711. In the past, I have also considered the wider context in my Year of Dance posts for 1714 to 1717.

Drury Lane opened for the 1714-1715 season on 21 September 1714 and the company gave 217 performances (including during its summer season) by the time it closed on 23 August 1715. The King’s Theatre opened on 23 October 1714 but, as London’s opera house, gave far fewer performances – only 42 by the time it closed on 27 August 1715. Lincoln’s Inn Fields reopened on 18 December 1714, following the decision of the new King George I to allow John Rich the use of his patent after some years of silence. By 31 August 1715 Rich’s new company had given 130 performances, a sign of its weakness against the senior established company at Drury Lane.

All three companies included dancing among their entertainments. The statistics for these offerings are interesting. Drury Lane offered entr’acte dancing in a little over 20% of its performances. At the King’s Theatre around 19% of its performances were advertised with dancing. Lincoln’s Inn Fields included entr’acte dancing in 96% of its performances, a startling statistic that proves the importance that Rich attached to dance from the very beginning of his career as the manager of one of London’s patent theatres.

The immediate change wrought by the reopening of Lincoln’s Inn Fields and the return to competition is highlighted by a few statistics from the 1713-1714 season, when the only theatres allowed to mount performances were Drury Lane and the then Queen’s Theatre. Drury Lane advertised 196 performances but included entr’acte dancing only during the benefit and summer seasons for around 11 % of the total. The Queen’s Theatre advertised dancing at only one of its 31 performances that season, with no mention of the dancers. However, the opera house’s practice of minimal advertising (because its performances were offered on subscription) make it very difficult to know how much dancing was actually offered there each season throughout much of the eighteenth century.

Returning to 1714-1715, Drury Lane billed a total of thirteen dancers (eight men and five women) in entr’acte dances, although only five of them – three men (Wade, Prince and Birkhead) and two women (Mrs Santlow and Mrs Bicknell) – gave more than a handful of performances. The advertisements suggest that Mrs Santlow and Mrs Bicknell were the chief draw when it came to entr’acte dancing. None of the men were named in advertisements before the early months of 1715, when Rich’s dance strategy had become obvious. Both Hester Santlow and Margaret Bicknell were well established as dancer-actresses with the company. John Wade and Joseph (or John) Prince were both specialist dancers, while Matthew Birkhead was an actor, singer and dancer.

Lincoln’s Inn Fields advertised eighteen dancers (fourteen men and four women) in the entr’actes during the season, but – as at Drury Lane – only ten of them were billed for more than a handful of performances. Ann Russell and Mrs Schoolding appeared throughout the season and both apparently made their London stage debuts following Rich’s opening of the theatre. Miss Russell was a dancer and would remain one throughout her career, without making the usual transition to a dancer-actress. She married Hildebrand Bullock, a member of the well-known acting family, on 3 May 1715 and would thereafter be billed as Mrs Bullock. Mrs Schoolding seems to have begun an acting career at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, alongside her appearances as a dancer. Letitia Cross was not billed until 5 July 1715 but gave at least ten performances before the end of the season. She had already enjoyed a long career as an actress, a singer and a dancer. Three of the men – Anthony Moreau, Louis Dupré and William Boval – made their London stage debuts this season. Newhouse may have appeared elsewhere in earlier seasons, but his appearance at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 8 February 1715 is the first record of him dancing at one of the patent theatres. Charles Delagarde was well established as a dancer and dancing master. John Thurmond Junior had appeared in London in earlier seasons, as had Sandham. All the men were specialist dancers.

The dancers who appeared regularly in the entr’actes could be said to form a ‘company within the company’ at each playhouse, even though several of them (the women in particular) acted as well as danced. Both acting companies mounted plays that included significant amounts of dancing in 1714-1715, but no casts were listed by either theatre in advertisements so it is impossible to be sure of the involvement of the dancers alongside the actors and actresses who danced only occasionally.

As for the entr’acte dances, Drury Lane offered nine, while Lincoln’s Inn Fields advertised seventeen. Drury Lane rarely mentioned specific dances in its advertisements, so it is impossible to know whether the repertoire was more extensive or which dances were the most popular. It seems likely that Mrs Santlow’s solo Harlequin was among the latter. She was billed in it twice during 1714-1715 and the dance had been popular since she first performed it, perhaps as early as 1706. This is the less familiar version of her portrait as Harlequine, the one she owned herself which shows her skirt at the length she probably wore for performance.

It was one of only two dances advertised by Drury Lane before the opening of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, after which the theatre did not bill dance titles again until the benefit season began. The theatre’s managers were initially slow to grasp the value of dancing to attract audiences in the new atmosphere of rivalry. Other dances that may have been more popular than the bills suggest were the duets Dutch Skipper and French Peasant, the first given by Wade and Mrs Bicknell and the second by Wade and Mrs Santlow. Both had become part of the entr’acte repertoire not long after 1700 and would remain popular into the 1740s.

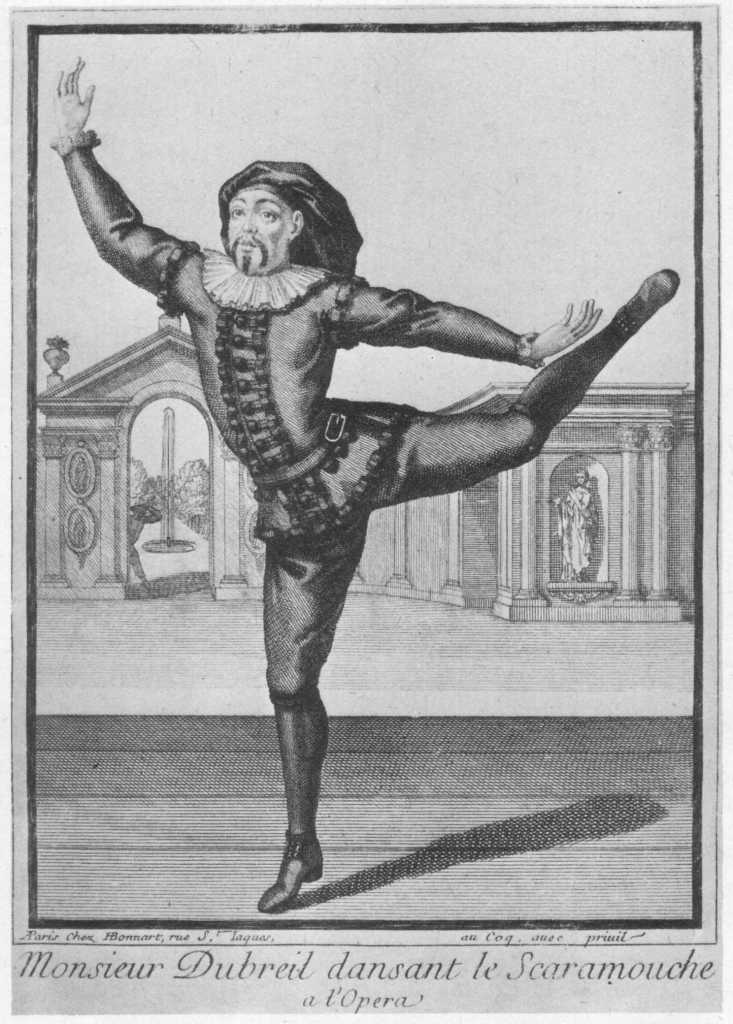

At Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the Dutch Skipper – first given on 6 January 1715 by Delagarde and Miss Russell – was far and away the most popular entr’acte dance, advertised twenty times by the end of the season. It was followed by a solo Scaramouch, performed on 5 February 1715 ‘by a Gentleman for his Diversion’ who gave it seven times during the season. John Thurmond Junior also danced a solo Scaramouch from 16 May 1715, when he was billed as ‘lately arrived from Ireland’. Scaramouch was already a familiar dancing character in London. John Thurmond Junior had been billed dancing the role ‘as it was performed by the famous Monsieur du Brill from the Opera at Brussels’ back in 1711. This print shows Pierre Dubreuil as Scaramouch about that time and suggests the acrobatic skills that Thurmond Junior may have emulated.

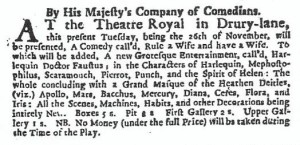

There were six entr’acte dances involving Scaramouch this season, with Lincoln’s Inn Fields leading the way and Drury Lane trying to catch up. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields, there was also an Italian Night Scene between Harlequin, Scaramouch and Punch (31 March 1715) and Scaramouches (18 April 1715, apparently a group dance although no dancers were named). Drury Lane replied with a Scaramouch and Harlequin (31 May 1715), a Tub Dance between a Cooper, his Wife, his Man, Scaramouch and Harlequin (2 June 1715) and Four Scaramouches (also 2 June 1715). In these dances, Harlequin would have been performed by one of the male dancers in the company. The four Scaramouches were probably danced by Prince, Wade, Sandham and Newhouse, who were listed in the bill (they also shared between them the male roles in the Tub Dance).

Delagarde and Miss Russell have a good claim to be the leading dancers at Lincoln’s Inn Fields this season, not only because of the number of their appearances (he was billed 65 times and she on 82 occasions) but also for their repertoire. As well as the Dutch Skipper, they performed a Spanish Entry, a Swedish Dance, a Venetian Dance and, most notably, The Friendship a new dance by Mr Isaac (who had been Queen Anne’s dancing master) which was also published in notation. The last of these may have been given before George I when he made his only visit of the season to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, on 10 March 1715 (he had visited Drury Lane on 5 January 1715). The new King was not proficient in English so limited his attendance at plays, preferring the Italian opera at the King’s Theatre. No serious dances were advertised at Drury Lane this season, whereas at Lincoln’s Inn Fields the Spanish Entry, an Entry and Mrs Bullock’s solo Chacone, given later in the season, can probably be assigned to the genre.

The 1714-1715 season should probably be seen as one of transition, at least so far as the dancing was concerned, as Drury Lane adjusted to the return of theatrical competition after enjoying several years of monopoly and Lincoln’s Inn Fields tried to gauge how it would deal with the dramatic superiority of its rival. Both theatres had to assess the impact of a new monarch and a new royal family on London’s theatrical life. In the following season of 1715-1716, they began to develop responses that would have a lasting effect on the entertainments of dancing to be seen on the London stage.