Following my recent detailed analysis of the 1725-1726 theatrical season on the London stage, I thought I should return to my A Year of Dance series and add 1726. (I wrote about 1725 quite some time ago). Politically, this seems to have been a quieter year than 1725.

In France in June, Louis XV appointed his old tutor André-Hercule de Fleury as his chief minister. Fleury was created a cardinal in September 1726. The previous spring, the poet and writer Voltaire had arrived in England for two years of exile from France following a second period of imprisonment in the Bastille. He quickly learned English, honing his language skills by regular visits to London’s theatres. During his stay he was to meet Alexander Pope, John Gay and Jonathan Swift, among others.

In England, 1726 was marked by the death of the architect and dramatist Sir John Vanbrugh on 26 March, followed by that of the scourge of London’s theatres Jeremy Collier on 26 April, whose A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage published in 1698 had attacked Vanbrugh among other leading playwrights. Towards the end of the year, George I’s former wife Sophia Dorothea of Celle died. Their marriage had been dissolved following her adultery in 1694 and she had been imprisoned in her native Celle for more than twenty years. 1726 also saw the publication of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (‘Lilliputians’ would in due course become a popular feature on the London stage), as well as the ‘rabbit’ hoax by Mary Toft which fascinated and bamboozled many over the autumn.

In the wider context for these posts, the most significant theatrical event of 1726 in London was the new pantomime at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Apollo and Daphne given on 14 January, which brought Francis and Marie Sallé back to the London stage after an absence of several years and reintroduced them to audiences as adult dancers. It answered Drury Lane’s 1725 Apollo and Daphne pantomime, which was revised and revived in reply. This small painting by the Italian artist Michele Rocca probably dates to the early 18th century.

There was also Italian opera at the King’s Theatre, with two new operas by Handel – Scipione on 12 March and Alessandro on 5 May. The Italian soprano Faustina Bordoni made her debut as Rossane in Alessandro, with Francesca Cuzzoni as Lisaura and Senesino in the title role.

In Paris, Destouches’s opéra-ballet Les Stratagèmes de l’Amour (composed to celebrate the marriage of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska the previous year) was given at the Paris Opéra on 28 March. The dancers included Françoise Prévost and David Dumoulin – she led the Troyennes in the first divertissement in Entrée I, while he led the Matelots in the second divertissement, and they danced together as Esclaves (with sixteen other dancers) in Entrée III. Rebel’s tragédie en musique Pyrame et Thisbé had its first performance on 17 October. David Dumoulin and Mlle Prévost also danced in this production, leading the Egyptiens (with Blondy) in act two and the Bergers and Bergères in act three.

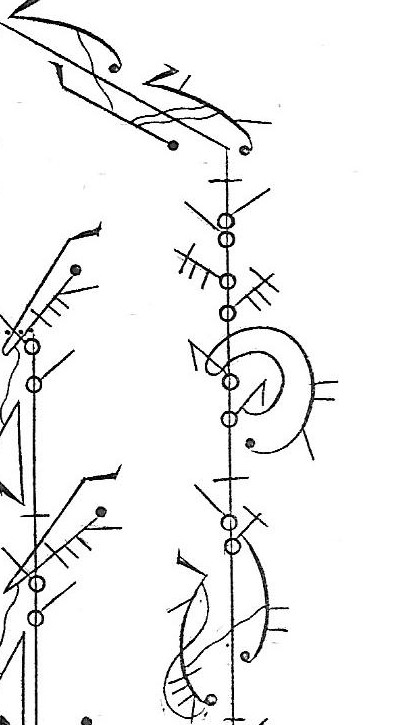

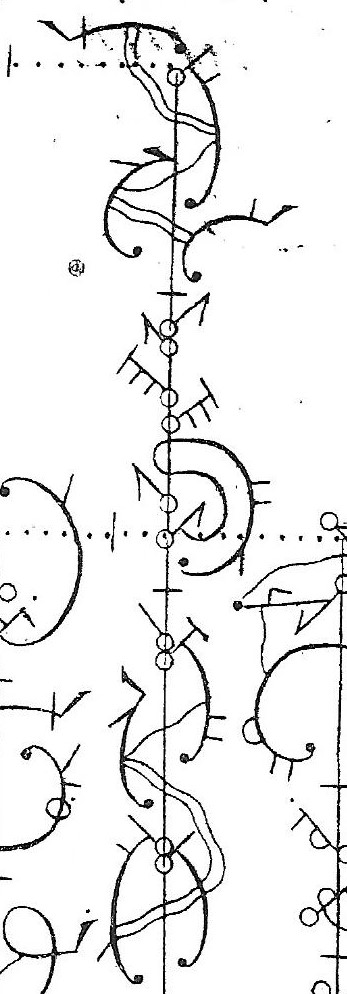

No dances were published in notation this year. The last of the Paris collections had appeared in 1725, while in England the series of new dances ‘For the Year’ by Anthony L’Abbé had already ceased to be annual. It would resume in 1727 and continue, with occasional gaps, until 1733.