I thought it would be interesting, and perhaps informative, to try to place Mr Isaac’s minuets within the context of other minuet choreographies of approximately the same period. It isn’t easy to date the French notated dances, other than by their dates of publication, but given that some use music that appeared earlier they, too, may have been created a few years before their first appearance in print. I have taken my investigation as far as 1709, the year that Isaac’s The Royal Portuguez was published. Apart from the minuet in Favier’s Le Mariage de la Grosse Cathos of 1688, which I include here, there are six other minuets to be explored. Some are minuets only, while others are minuet sections within multi-partite dances.

La Bourée d’Achille was first published in Feuillet’s Recueil de dances composées par Mr. Pecour in Paris in 1700, one of the first two collections of dances to appear in notation. The minuet is the central section of the dance, with 48 bars of music in 3/4 time (2xAABB A=4 B=8), preceded and followed by a bourrée. The music is from Achille et Polixène, the opera begun by Lully and completed after his death by Colasse. It was first performed in 1687 and then not revived until 1712. So, the duet must antedate 1700 and could belong to the mid to late 1690s.

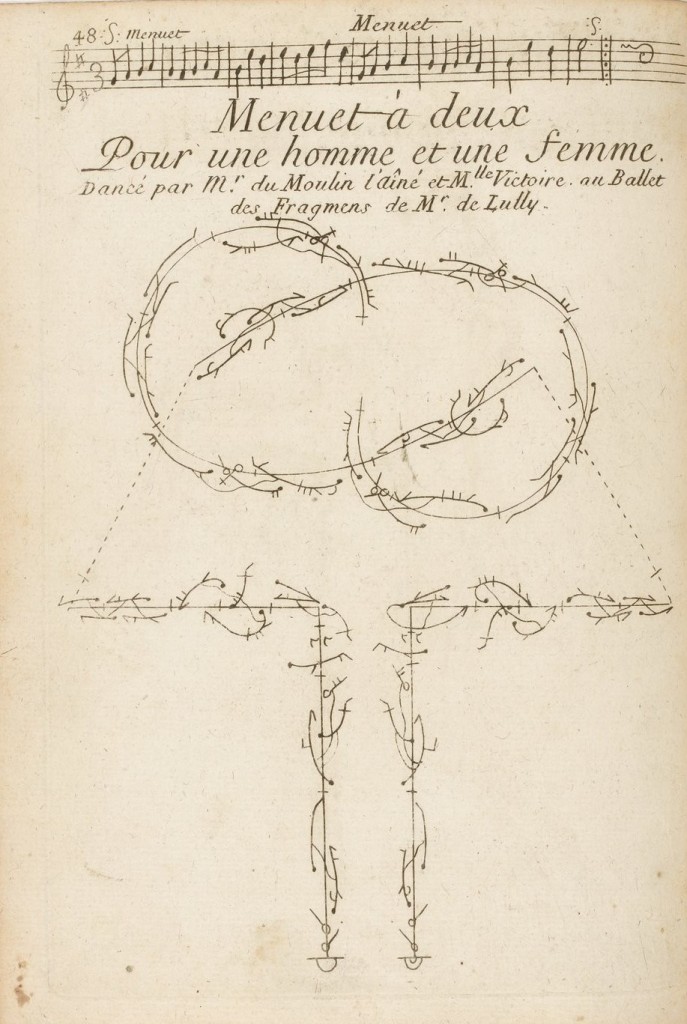

The Menuet à Deux was published by Feuillet in Recueil de dances contenant un tres grand nombres, de meillieures entrées de ballet de Mr. Pecour which appeared in Paris in 1704. This was the first collection of dances closely linked to the Paris Opéra (Feuillet had published a collection of his own ‘theatrical’ choreographies in 1700, but these seem not to have been associated with dancers on the professional stage). It was danced by Dumoulin l’aîné and Mlle Victoire in Campra’s Fragments de Mr de Lully in 1702 and the choreography obviously belongs to that date. As its title suggests, this is a minuet throughout which has 48 bars in 3/4 time (AABB A=8 B=16)

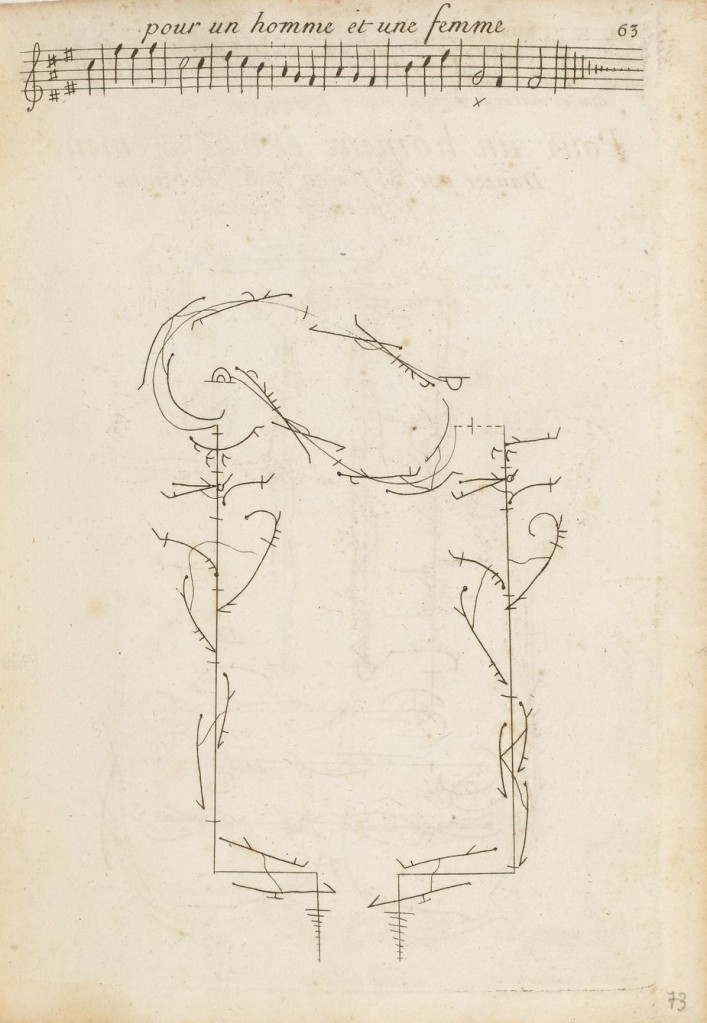

The Entrée pour un homme et une femme was also choreographed by Pecour and included in the 1704 Recueil de dances. The music is from Destouches’s opera Omphale, first given at the Paris Opéra in 1701 and then at court in 1702 (after which it was not revived until 1721). The notation declares that this duet was performed by Ballon and Mlle Subligny. It was, of course, a minuet for the stage rather than the ballroom with 68 bars of music in 3/4 time (a rondeau, ABACA A=16 B=8 C=12)

La Bavière, choreographed by Pecour, appeared in the IIIIe Recueil de dances de bal pour l’année 1706 published in Paris the previous year. This is a minuet followed by a forlana, to music from La Barre’s La Vénitienne first given at the Paris Opéra in 1705, so this ballroom dance must surely have been created with speedy publication in mind. The minuet has 32 bars of music in 3/4 time (AABB A=B=8)

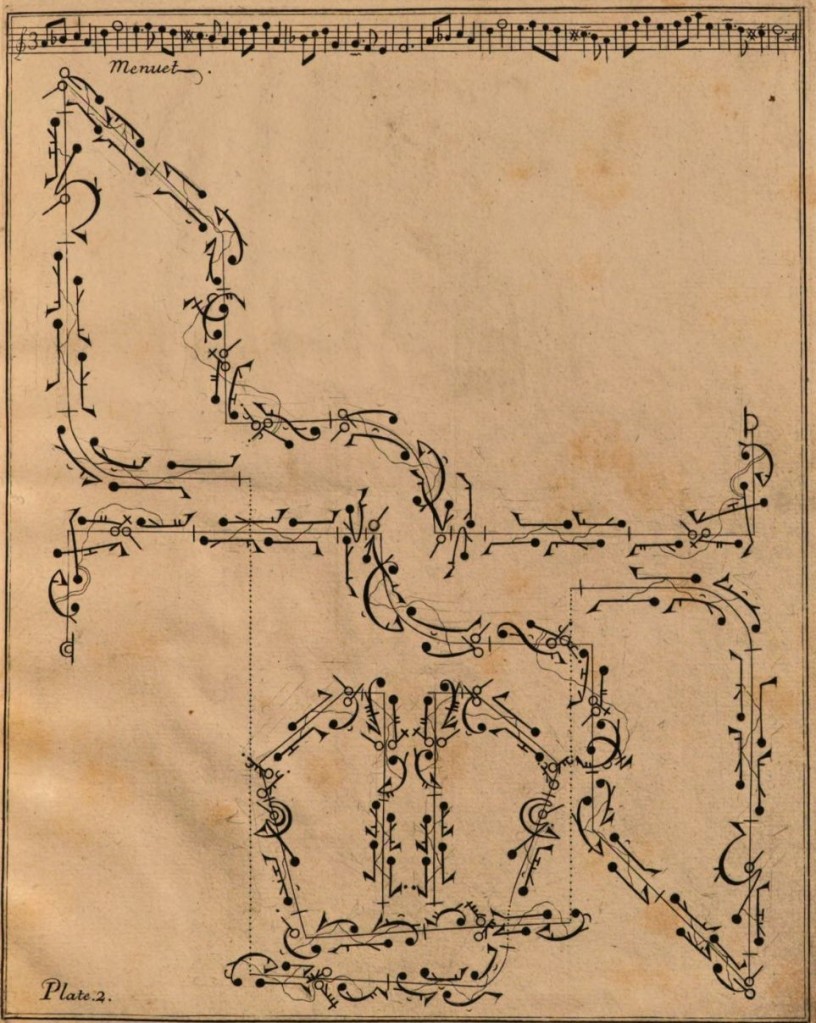

The Brawl of Audenarde, by Siris, was published individually in London as his ‘new Dance for the year 1709’ and was obviously intended to celebrate the Duke of Marlborough’s victory at the Battle of Oudenarde as part of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1708. The title page says ‘The Tune by Mr. G.’, John Ernest Galliard, and the music was published separately the same year. This dance is a courante followed by a minuet and then a gigue, so it has structural affinities with some of Mr Isaac’s choreographies. The minuet has 32 bars of music in 3/4 time (ABAB A=B=8).

Le Menuet d’Alcide, another choreography by Pecour, was also published in 1709 but in Paris within the VIIe Recüeil de dances pour l’année 1709. Its music is from the opera Alcide by Louis Lully and Marin Marais, first performed at the Paris Opéra in 1693 and revived in 1705 (according to Francine Lancelot’s catalogue La Belle Dance (entry FL/1709.1/02) the music was also used in Ariane et Bacchus by Marais in 1696). This is another minuet throughout with 54 bars of music in 6/4 (3xAABB’ A=4 B=6 B’=4). It is possible, but perhaps unlikely, that Pecour’s choreography dates to the mid to late 1690s.

Leaving aside issues of dating, do any of these minuets have steps or figures in common with those by Mr Isaac that I explored in my earlier post?

Favier’s minuet ‘Entrée des 2. Garçons et des 2. filles de la Nopce’ in Le Mariage de la Grosse Cathos is analysed in detail by Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Carol Marsh in their 1994 book Musical Theatre at the Court of Louis XIV (see particularly pages 144-148). This choreography uses pas de menuet and contretemps du menuet, plus a single coupé and assemblé combination. The pas de menuet and contretemps du menuet differ from later versions, both in their component steps and their timing (see Harris-Warrick and Marsh, pp. 109, 111). There is no reference to any of the later conventional figures of the ballroom minuet. This ‘Entrée’ is a stage choreography performed within a work which uses music, songs and dances to portray an event – the marriage of ‘Fat Kate’. It is, perhaps, more surprising that it uses a standard and restricted vocabulary of steps than that it ignores the usual figures of the minuet, if these had indeed been established by 1688.

The French ballroom dances published in the early 1700s all reflect the menuet ordinaire as known from Rameau’s Le Maître à danser of 1725. The minuets in La Bourée d’Achille and La Bavière, as well as Le Menuet d’Alcide, all predominantly use the pas de menuet with some contretemps du menuet and occasional grace steps. In La Bourée d’Achille the pas de menuet à trois mouvements is favoured, while in Le Menuet d’Alcide preference is given to the pas de menuet à deux mouvements. The figures of these two minuets (particularly the latter) recognisably relate to the conventional figures of the ballroom minuet, but the minuet section in La Bavière is too short to do other than allude to the opening figure before moving on to another short figure which simply gets the dancers to their places to begin the following forlana.

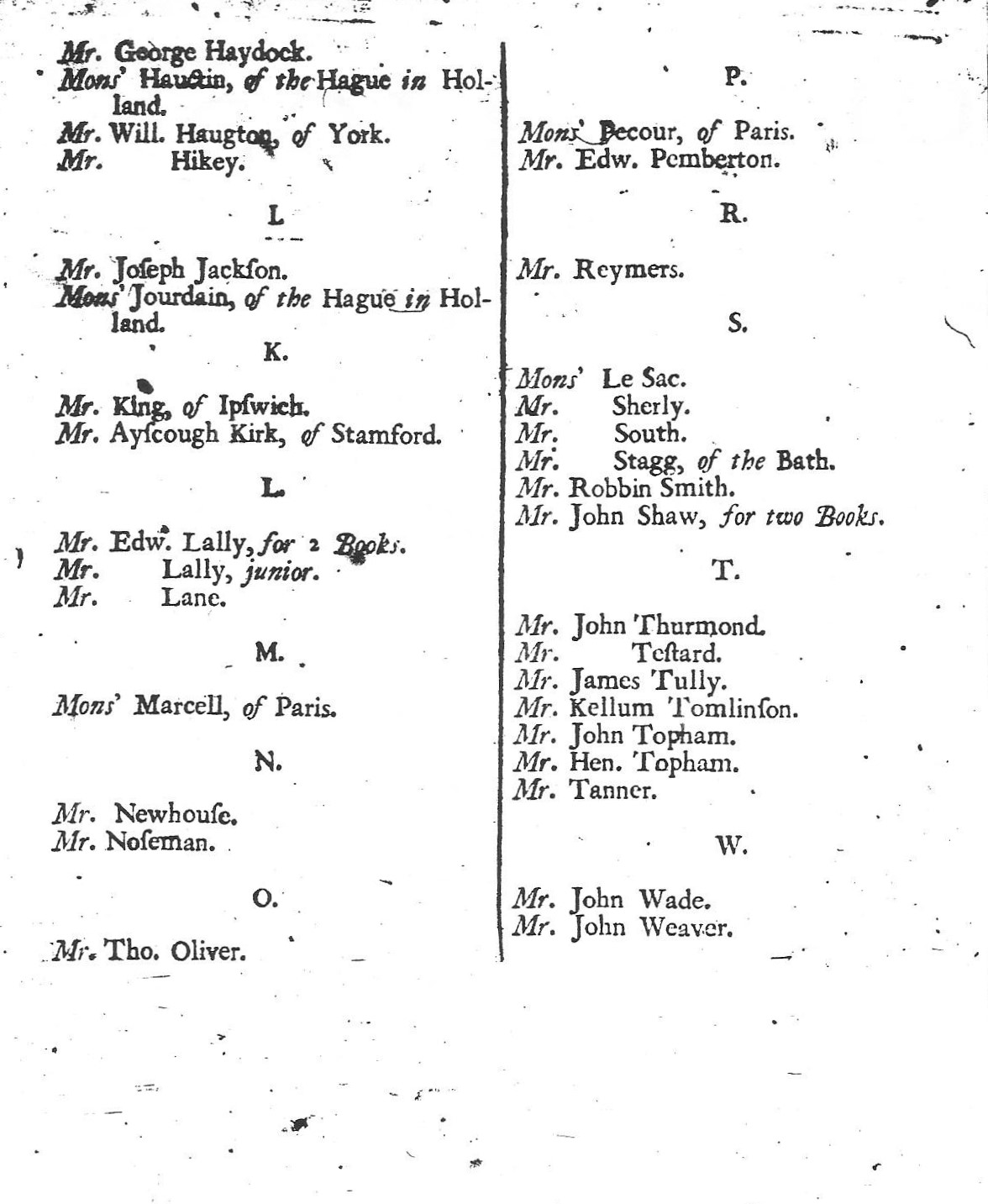

Of the two minuets for the stage, the Menuet à Deux danced by Dumoulin l’aîné and Mlle Victoire is the most conventional. Of the twenty-four pas composés in this dance (which are written as if in 6/4), ten are pas de menuet à deux mouvements and eight are contretemps du menuet. Pecour begins the dance with a coupé sideways as the couple face each other, followed by a pas tombé and a jetté. The first B section of the music begins with the couple facing one another on a right line for a pas balancé forwards and backwards, incorporating a beat and an ouverture de jambe, before moving sideways away from each other with a fleuret and a pas balonné. They then repeat this sequence. Despite his choice of steps, Pecour seems not to reflect any of the ballroom minuet’s figures within his choreography – although this dance has quite a strong inward focus between the two dancers which is interesting in the context of a stage performance. Here is the first plate.

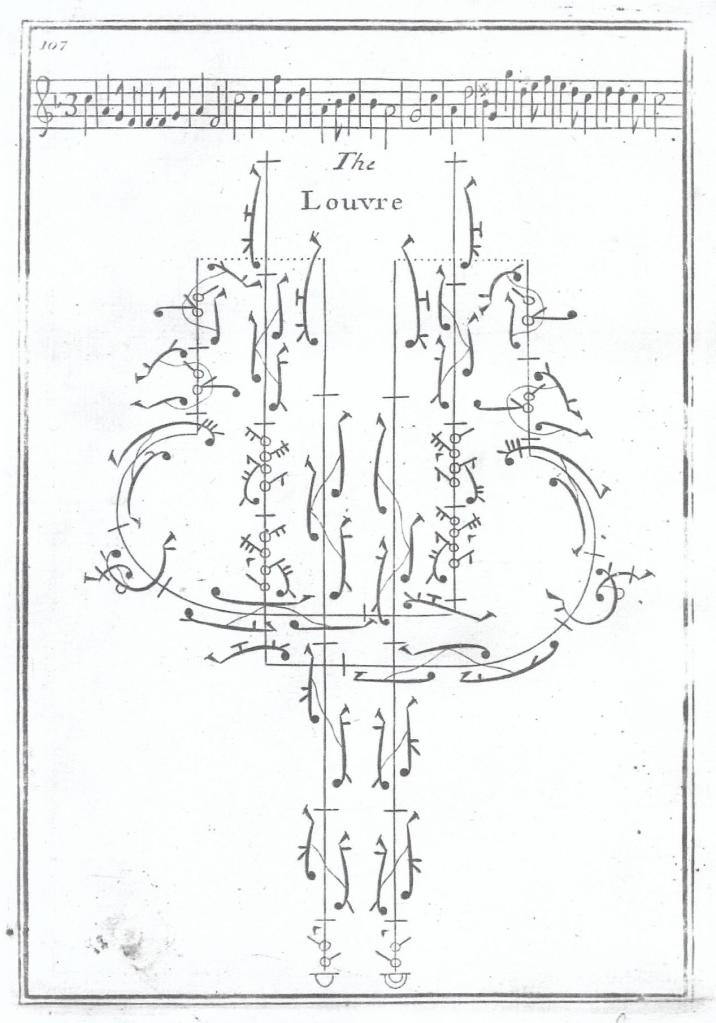

The Entrée pour un homme et une femme, danced by Ballon and Mlle Subligny in Omphale, has a far more varied vocabulary of steps with only four pas de menuet à deux mouvements and two contretemps du menuet. Otherwise Pecour uses pas composés based on a wider range of basic steps, some of which play with conventional steps from the minuet, for example the demi-contretemps followed by a pas tombé and a jetté, while others come together into sequences which echo those he uses in other dance types, like the coupé à deux mouvements followed by a coupé sans poser as the couple move sideways away from each other. There are no clear references to the conventional figures of the minuet, although the final retreat does have a contretemps du menuet as the pair move backwards upstage. Here is the final plate of this duet.

It is worth noting that this dance is far more outwardly focussed than Pecour’s Menuet à Deux. It is less easy to identify as a minuet from its choreography, but I suspect that a subtle relationship with the conventions of the ballroom minuet might emerge in the course of detailed reconstruction of the duet.

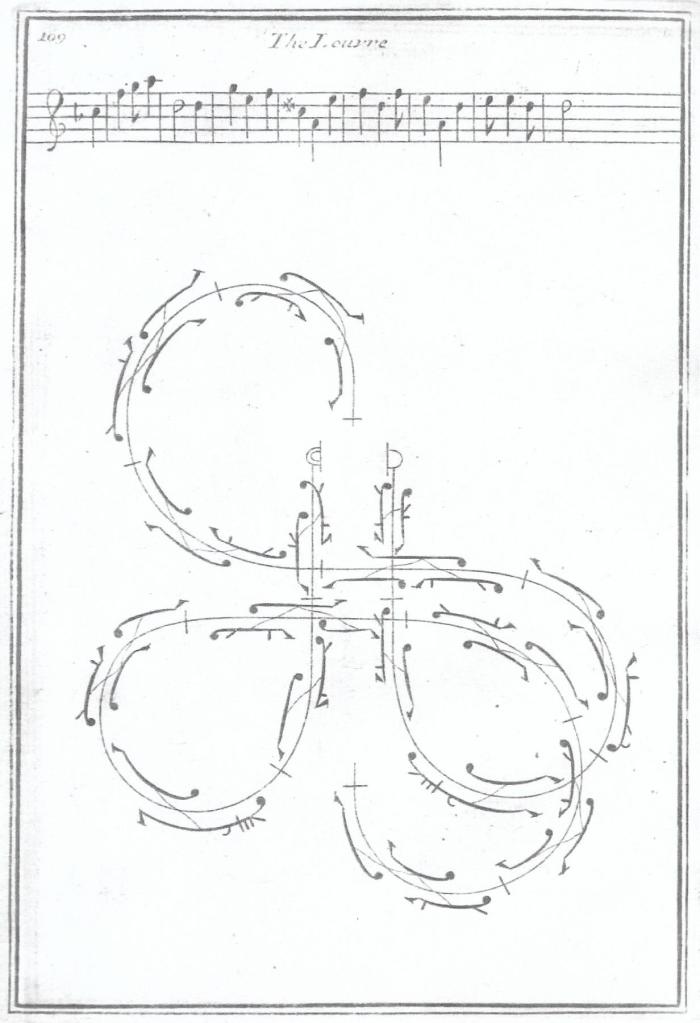

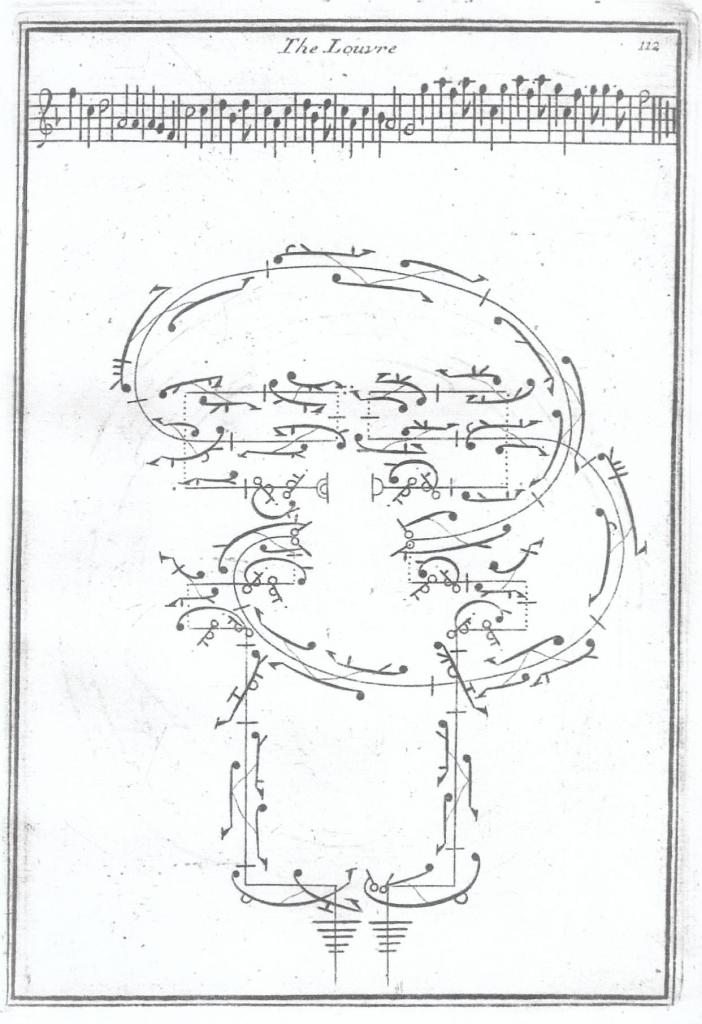

The last of the minuets seems to relate most closely to those by Mr Isaac, perhaps because Siris was working in London as well, or maybe because he was trying to emulate some aspects of Isaac’s choreographic style. Here is plate two of The Brawl of Audenarde with the whole of the minuet section.

The notation and engraving styles are strikingly different from those of the French notations and resemble those of Isaac’s dances (the printer John Walsh produced both Isaac’s and Siris’s dances). The dancers have just completed the courante, the opening section of the duet, and are facing each other offset across the dancing space. They begin by moving onto the same diametrical line with a variant of the pas de bourrée in which the last step is a pas glissé, recognisable from Isaac’s minuet for The Britannia, to which Siris adds a final plié. This is joined to a hop and a jetté, the final elements of the contretemps du menuet, to make a new hybrid pas composé emulating the sort of steps created by Isaac. Siris makes copious use of the pas de menuet à deux mouvements – there are seven in all within this 16-bar minuet (although the music is notated in 3/4, the dance steps are written in 6/4) and four are given small variations. There is a grace step, the pas de courante, which appears once in its usual guise of a tems de courante followed by a demi-jetté battu and then in an ornamented version (performed by the woman as well as the man) which has a double beat. The latter comes close to the end of the minuet section, by which time the couple are in mirror symmetry and so dancing on opposite feet. Like La Bavière, the minuet section of The Brawl of Audenarde is too short to include even allusions to the figures of the ballroom minuet. It ends with the man and woman side by side facing the presence, but improper, ready to begin the gigue with which the duet ends.

On the evidence of this small selection of early notated minuets, six French and one English (or, at least, published in London), Mr Isaac’s choreography was very idiosyncratic. The nearest to him in style is Siris. Should we read anything into the fact that, in his own translation of Feuillet’s Choregraphie entitled The Art of Dancing, Demonstrated by Characters and Figures and published in London in 1706, Siris claimed that he had been taught the notation by its inventor Pierre Beauchamp in the late 1680s? As we now know, Mr Isaac had begun his career in Paris by the early 1670s and was undoubtedly acquainted with Beauchamp. Did he and Siris enjoy similar early training in belle danse, contributing to the similarities between their approaches to choreography?