Francis Peacock published Sketches relative to the history and theory, but more especially to the practice of dancing in 1805 in Aberdeen, the city where he had been dancing master since 1747. His treatise pursues themes familiar from many earlier such works, as his contents pages show.

Peacock’s book is best known for Sketch V, with its ‘Observations on the Scotch Reel’ along with a ‘Description of the Fundamental Steps’ of that dance. He provides the only known account of this vocabulary, although there is much discussion among today’s teachers of historical dance as to how ‘Scotch’ his steps may have been. Even experts in Scotland’s traditional dancing suspect the influence of ‘French’ dancing in what Peacock has to say.

I am not going to pursue that question, but I am going to look at what Peacock tells us about his own early training to see if that might contribute any useful information relating to his later writing. He provides some helpful clues in the ‘Advertisement’ to his Sketches.

Peacock tells us that he learnt his craft from three of London’s leading dancing masters – George Desnoyer, Leach Glover and Michael Lally, all of whom were also leading dancers in London’s theatres. At an informed guess, he studied with them between the late 1730s and early 1740s. It seems most likely that he had private tuition. He apparently did not follow any form of apprenticeship, which would have bound him to one of these dancing masters for several years and not allowed him to take lessons from all of them. What might they have taught him above and beyond what we know from other dance manuals like Rameau’s Le Maître à danser?

George Desnoyer (c1700-1764?) was possibly born in Hanover, since he was the son of the electoral court’s dancing master (who was probably French and perhaps danced at the Paris Opéra around 1690). Desnoyer is first recorded when he came to dance in London in 1721. L’Abbé’s ‘Spanish Entree’, ‘Entrée’ and ‘Türkish Dance’ created for him, and published in notation around 1725, give us an idea of the young Desnoyer’s virtuosity. In 1722, he returned to Hanover to take up the post of dancing master to Prince Frederick, son of George Prince of Wales, which he held until the Prince was called to London by his father, then George II, in 1728. Desnoyer was not formally dismissed from his post as court dancing master in Hanover until 1731, but by then he was already employed as ‘first Dancer to the King of Poland’ – as he was described in the bills when he returned to London that year. He danced at Drury Lane most seasons from 1731-1732 to 1739-1740 and then at Covent Garden from 1740-1741 to 1741-1742, his final seasons on the stage. On his return to London in 1731, Desnoyer had resumed his relationship with Prince Frederick (the two seem to have been close friends) and he would be dancing master to the Prince, his wife Princess Augusta and their children (including the future George III) until his death.

Leach Glover (1697-1763) was born in London, but not to a theatrical family. He may have begun his career as an actor, but he was first advertised as a dancer at the King’s Theatre in 1717. In his first season on the London stage, Glover was billed as ‘de Mirail’s Scholar’ and he was indeed a pupil of Romain Dumirail, the French dancer and teacher who had worked at the court of Louis XIV and the Paris Opéra. Between 1717 and 1723, Glover’s appearances in London were intermittent and he usually danced with companies of French comedians. He joined John Rich’s company at Lincoln’s Inn Fields for the 1723-1724 season and stayed with Rich until 1740-1741, his last season on the stage. Over that period, Glover rose from a supporting dancer to the company’s leading male dancer (in 1739-1740) before he was eclipsed by the arrival of Desnoyer at Covent Garden. Glover was appointed as royal dancing master in 1738, in succession to Anthony L’Abbé, although Desnoyer continued to teach Prince Frederick and his family. He created a ballroom duet The Princess of Hesse to celebrate the marriage of George II’s daughter Princess Mary in 1740 and it was published in notation.

Michael Lally (1707-1757) came from a family of dancers working in London’s theatres from the late 17th to the mid-18th century. Their respective careers are yet to be properly disentangled (the entries in the Biographical Dictionary of Actors require much revision). Michael was the son of Edmund Lally and brother of Edward Lally (born 1701), who were among the subscribers to John Weaver’s Anatomical and Mechanical Lectures upon Dancing in 1721. He may have made his stage debut in 1720, dancing for his brother’s benefit at Drury Lane. With his brother, he danced briefly at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but returned to Drury Lane for the 1723-1724 season and stayed there for ten years. He joined John Rich’s company at Covent Garden in 1734-1735 and continued to work there until 1742-1743, although after 1737 he danced only at his annual benefit performances (he may have been dancing master to the company). Advertisements confirm that Michael Lally was a leading dancer first at Drury Lane and then at Covent Garden.

During the period when Francis Peacock may have studied with them, all three men were active as both dancers and dancing masters. They assuredly provided him with a grounding in French belle danse as practised in the ballroom, but could their teaching have gone further? Might they have included ‘Scotch Dancing’ as part of their tuition? Although all three were best known on stage for their serious dancing, they did also perform in other genres – including Scotch Dances.

Desnoyer came to Scotch Dances right at the end of his career. During his last season on the London stage, he danced a ‘New Scots Dance’ with Sga Barbarina (the Italian ballerina Barbara Campanini) at his benefit on 1 April 1742. They performed the duet together at least four times. It is worth noting that at the same performance Desnoyer and Sga Barbarina also danced ‘A Ball Dance call’d the Britannia [probably Pecour’s La Bretagne of 1704], and a Louvre concluding with a Minuet’. The ‘Louvre’ was Pecour’s Aimable Vainqueur. All three choreographies were routinely taught by London’s dancing masters. Glover choreographed his own Scotch Dance, for three couples, and it was first given at Covent Garden on 16 January 1733. It was one of the most popular of the Scotch Dances in London’s theatres and remained in repertoire until the 1740-1741 season. Like Desnoyer, Glover regularly performed the Louvre, usually with a Minuet, at his own and other benefits. Lally is not known to have performed other than a solo Highland Dance, given early in his career during the 1722-1723 season. However, like Desnoyer and Glover, he regularly performed the Louvre and a Minuet at his benefit performances.

Even if none of his teachers could or would have taught Francis Peacock a Scotch Dance, he would have been able to see such choreographies quite frequently in London’s theatres. As I explained in my post Scotch Dances on the London Stage, 1660-1760, there was a surge in their popularity during the mid-1730s which lasted into the early 1740s and even beyond – just at the time that Peacock must have been in London.

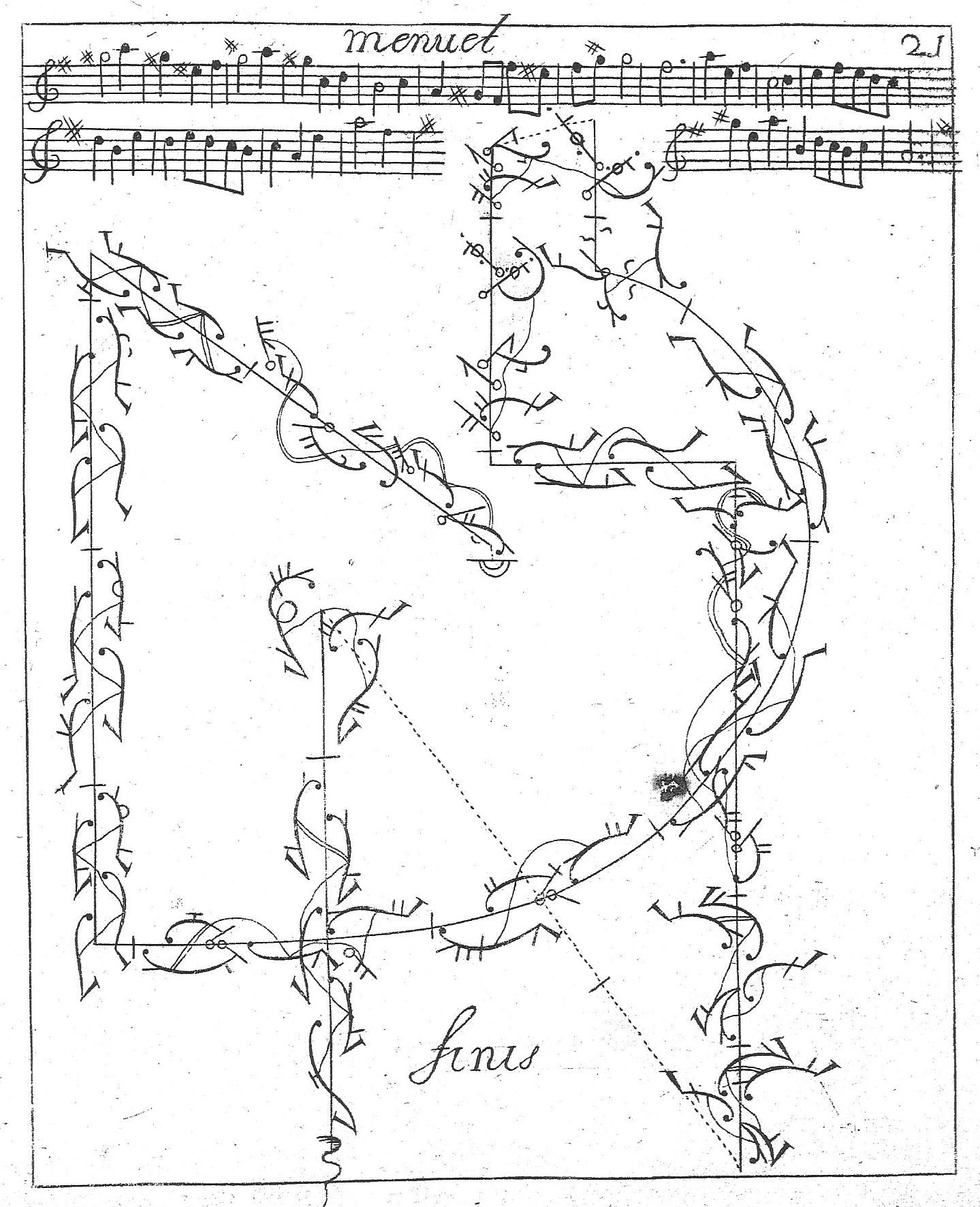

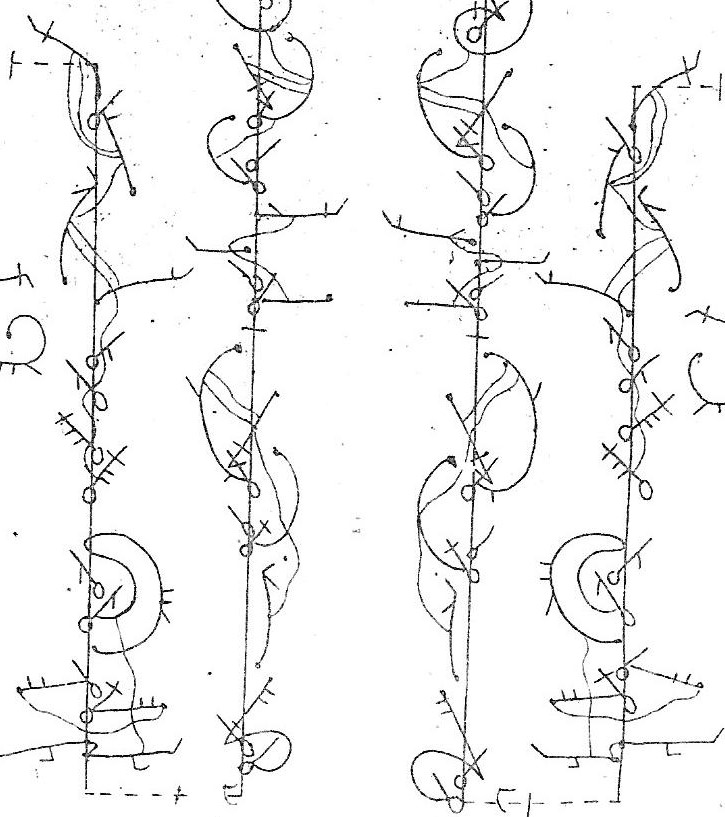

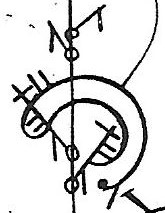

While the evidence I have brought together here remains inconclusive as to whether Francis Peacock might have learnt Scotch Dances while he was in London, it does suggest that Scotch Dances and French dancing had plenty of opportunities to influence each other during the years when he was taking lessons with Desnoyer, Glover and Lally. The following illustrations – one plate from L’Abbé’s ‘Spanish Entrée’ for Desnoyer with two entre-chats à six and Peacock’s description of the ‘Kem Badenoch’ with its mention of an ‘Entrechat’ – may perhaps provide food for thought.

References:

I have written more about Desnoyer and Glover elsewhere (I am currently working on an article about the Lally family).

Moira Goff, ‘Desnoyer, Charmer of the Georgian Age’, Historical Dance, 4.2 (2012), 3-10.

Moira Goff, ‘The Celebrated Monsieur Desnoyer, Part 1: 1721-1733, Part 2: 1734-1742’, Dance Research, 31.1 (Summer 2012), 67-93.

Moira Goff, ‘Leach Glover, “Dancing Master to the Royal Family”, Part One: The Professional Dancer in Context, Part Two: Teachers of Dancing’, Dance Research (forthcoming).

Apart from his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, I couldn’t find any articles devoted to Francis Peacock either in print or online, although he does of course feature in George S. Emmerson’s A Social History of Scottish Dance (Montreal, 1972).