The following solo entr’acte dances were given at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1725-1726:

Scotch Dance

Wooden Shoe Dance

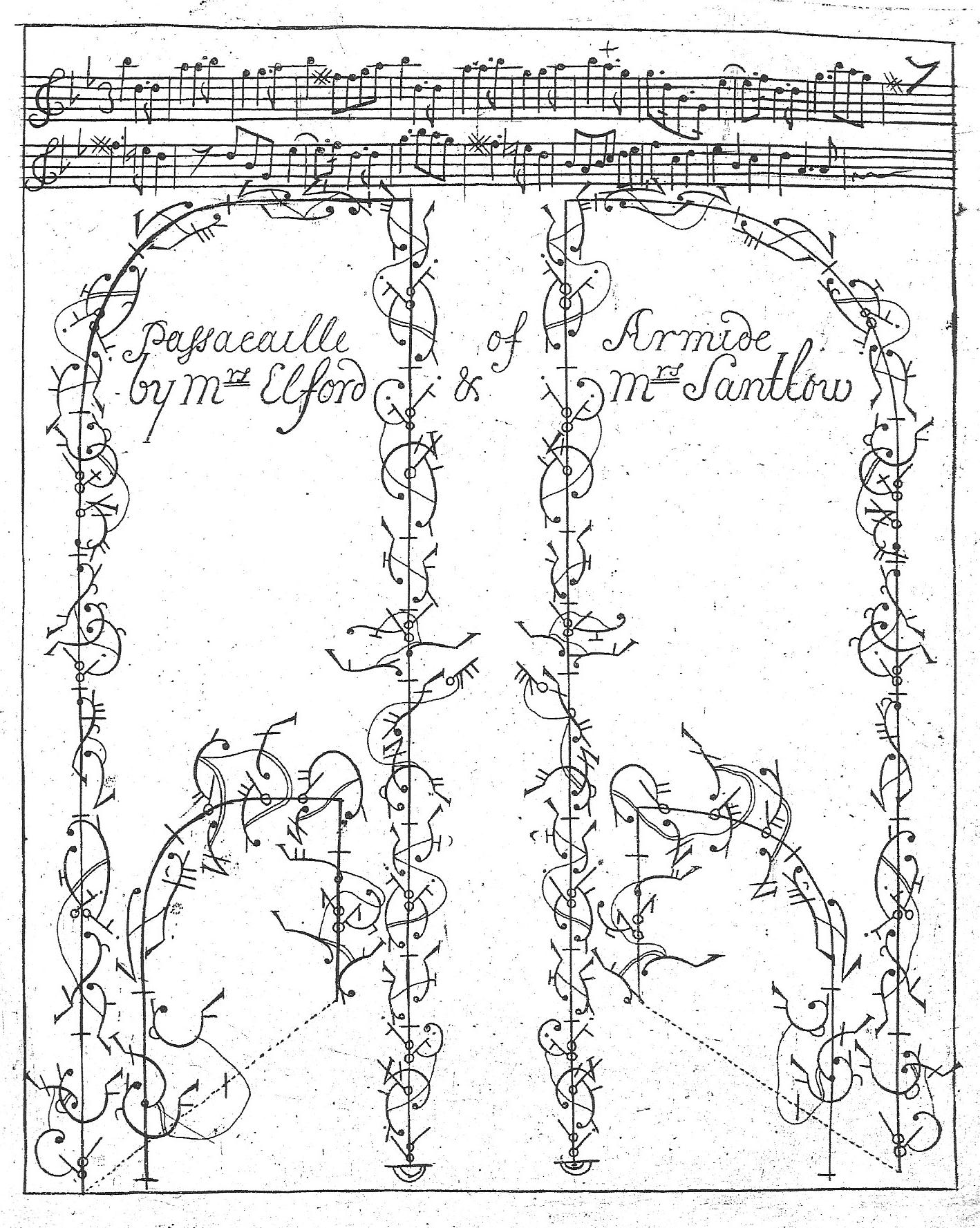

Passacaille

Les Caractères de la Dance

French Sailor

French Clown

Chacone

Louvre

Flag Dance

Dutch Boor

Saraband

Spanish Dance

Dame Gigogne

As I mentioned in my last post about the entr’acte solos at Drury Lane, this season the Passacaille and the Spanish Dance were also performed there.

I recently wrote a post about Scotch Dances on the London stage and I began by mentioning those performed during the 1725-1726 season. Mrs Bullock performed a solo Scots Dance at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 4 October 1725 and repeated it at least ten times that season. Thanks to her and Newhouse (who performed a Scottish Dance with Mrs Ogden at least five times this season), Scotch Dances had become a regular feature in the entr’actes by the mid-1720s. Although we still don’t know much about them and where they might have come from.

On 13 October 1725, Nivelon performed a Wooden Shoe Dance and repeated what was surely the same dance ‘in the Character of a Clown’ (meaning a rustic or peasant) on 25 October. The solo was billed simply as a Wooden Shoe Dance for the rest of the season and he performed it at least eleven times. There had been occasional Wooden Shoe Dances as early as 1709-1710, but it was Nivelon who established them in the entr’acte repertoire. He sometimes danced a Wooden Shoe duet with Mrs Laguerre (although not in 1725-1726), but his solo was far more popular.

Only one of the many solos and other dances given in the entr’actes at London’s theatres over the course of the 18th century is widely known among those with an interest in dance history. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 27 November 1725, Marie Sallé performed ‘Les Caractères de la Dance, in which are express’d all the different Movements in Dancing’. The description refers to Rebel’s score, which runs through the courante, minuet, bourée, chaconne, saraband, gigue, rigaudon, passepied, gavotte, loure and musette in some eight minutes or so. This dance (which was also occasionally performed as a duet) has been much discussed and often recreated. Its history on the London stage is worth a post of its own, so I won’t say much here. Mlle Sallé gave it three times during the 1725-1726 season. It was revived by her once in 1726-1727 and then several times as Les Caractères de l’Amour (which I assume was essentially the same) in 1733-1734, her penultimate season on the London stage. The solo obviously proved popular, because it was performed by several of London’s leading female dancers into the early 1750s.

A solo French Sailor was apparently danced at Lincoln’s Inn Fields by Francis Sallé on 3 January 1726. I have been wondering whether this really was a solo, since every other performance of the French Sailor this season was a duet by both Sallés. There is no other reference to Francis giving a solo Sailor’s Dance, with the exception of his appearance in a Sailor’s Hornpipe in 1729-1730. The advertisement refers to ‘Mons Salle’s French Sailor’, which may simply be meant to draw attention to the fact that he had created the duet that he danced with his sister. Of course, he may simply have adapted that duet into a solo to be performed alongside the solo French Peasant by Nivelon and Mrs Bullock’s solo Scotch Dance on the same bill.

On 31 March 1726, Nivelon danced a solo French Clown. Although he was occasionally so billed, he was more often advertised in a Clown solo (he appeared at least once as a Dutch Clown). Nivelon’s repertoire, in particular his appearance in pantomime afterpieces, needs careful analysis, but it is possible that the main difference between these three solos was their costumes rather than their choreographies. The term ‘Clown’ can have rustic connotations, but perhaps Nivelon’s solo was related to the ‘Buffoon’ depicted by Lambranzi, who describes his performance thus (the translation is from New and Curious School of Theatrical Dancing translated by Derra de Moroda, edited by Cyril Beaumont and first published in 1928, p. 25):

‘This buffoon does various foolish but curious pas, with distorted but comic jumps, which he varies as much as possible and endeavours to make still more humorous, until the air has been played three times.’

Lambranzi shows the Buffoon performing a suitably distorted pas.

In 1725-1726, four different female dancers performed a solo Chacone in the entr’actes at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The first was Mrs Bullock on 31 March 1726, followed on 9 May by Mrs Anderson, on 11 May by Miss Latour and on 14 May by Mrs Wall. All were benefit performances (Miss Latour was dancing at her own benefit). Mrs Anderson went on to perform her solo Chacone another eight times during the theatre’s summer season. Without their music, it is difficult to know what these solos might have been like. Were they related to Pecour’s ‘Chacone pour une femme’ danced to music from Lully’s Phaëton and published in notation in 1704? Mrs Bullock’s Chacone was part of her repertoire from 1714-1715 to 1734-1735 and undoubtedly changed over the years. What little evidence we have of her technical abilities (in the form of L’Abbé’s ‘Saraband of Issee’ and ‘Jigg’ created for her and Dupré) suggests that she could be a virtuoso dancer. Was her solo Chacone popular because it was a tour de force?

Leach Glover made his first appearance of the season on 14 April 1726, a benefit for Mrs Laguerre and her husband, when he danced a solo Louvre. Most advertisements for the Louvre referred to the duet Aimable Vainqueur, a favourite for benefit performances, but solo billings point to quite different dances. They are never billed explicitly as such, but at least some of them may have been ‘Spanish’ dances using loures either from Lully’s Le Bourgeois gentilhomme or Campra’s L’Europe galante. There was a recent precedent for such a solo in L’Abbé’s ‘Spanish Entrée’ created for the young George Desnoyer in 1721 or 1722 and published in notation around 1725.

This solo was to Lully’s music and provides a glimpse of the male dance virtuosity to be seen in London’s theatres at this period. This first plate includes cabrioles and a pirouette with pas battus (in modern terminology petits battements). Later in the solo there are several entre-chats à six, some of which are incorporated into tours en l’air.

At his benefit on 15 April 1726, Nivelon included his solo Flag Dance – a piece that he seems to have had a near monopoly on. He apparently introduced it to the London stage at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1723-1724 and was last billed performing it in 1730-1731. This is another piece which might have a link to Lambranzi, who has a dance by a ‘Switzer’ with a ‘standard’.

Nivelon’s dance may also have been related to the ‘Flourishing of the Colours’ performed by Signora Violante at the King’s Theatre in 1719-1720.

Nivelon was very busy in the entr’actes during 1725-1726, for on 15 April he also added a Dutch Boor to his repertoire. As I have mentioned in earlier posts, ‘Dutch’ dances were very popular on the London stage, although – apart from the Dutch Skipper – solo dances were far less often performed than duets. By London audiences, a ‘Dutch Boor’ was probably seen as a Dutch peasant or country bumpkin. Nivelon was rarely seen in ‘Dutch’ dances and this seems to be the only time he performed such a solo on its own.

Mrs Wall danced a solo ‘new Saraband compos’d by Dupre’ at the benefit she shared with Newhouse on 30 April 1726. It is possible that she had been taught by Dupré, although this was not mentioned in the bills. I wrote about the Saraband on the London Stage back in 2015, so I won’t say more here – except to suggest that this solo was a ‘French’ rather than a ‘Spanish’ Saraband.

There was a solo Spanish Dance at Lincoln’s Inn Fields this season, given by Lesac on 11 May 1726 – his benefit shared with Miss Latour, both of them billed earlier in the season as scholars of Dupré. Could this also have been a loure?

The last of the solos danced at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1725-1726 was a ‘new Comic Dance called Dame Gigogne’ performed by Mrs Anderson on 5 July 1726. This seems to be the only mention of this character in the entr’actes at London’s theatres. Dame Ragonde, however, turns up several times, notably in the mid-1710s, usually alongside various commedia dell’arte characters and sometimes with her ‘Family’. Dame Gigogne and Dame Ragonde are all but interchangeable and can be traced back in dance and music contexts to the late 17th century, notably to the cast of Le Mariage de la Grosse Cathos given at Louis XIV’s court in 1688. For a short discussion of both characters and their history see Musical Theatre at the Court of Louis XIV by Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Carol G. Marsh (1994), particularly pages 41-43. This image of Dame Ragonde may hint at Mrs Anderson’s appearance in her solo.

She is shown as a lady of uncertain age in a distinctly old-fashioned dress.

I will turn my attention to dancing in the pantomime afterpieces at both playhouses next, although one or two other topics may intervene over the next few weeks.