Around 1725, Le Roussau published A New Collection of Dances – thirteen choreographies ‘That have been performed both in Druy-Lane [sic] and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, by the best Dancers’ created by Anthony L’Abbé and notated by Le Roussau himself. The dancers were named on the title page as Ballon, L’Abbé, Delagarde, Dupré and Desnoyer with Mrs Elford, Mrs Santlow, Mrs Bullock and Mrs Younger. All were leading dancers in London’s theatres. The collection provides a series of snapshots of stage dancing in London between 1698 and 1722. It also gives us an insight into the world of professional dancers and dancing masters, through the ‘List of the Masters, Subscribers’ which precedes the notated dances. They are the individuals who made publication possible by paying in advance for the printed copies.

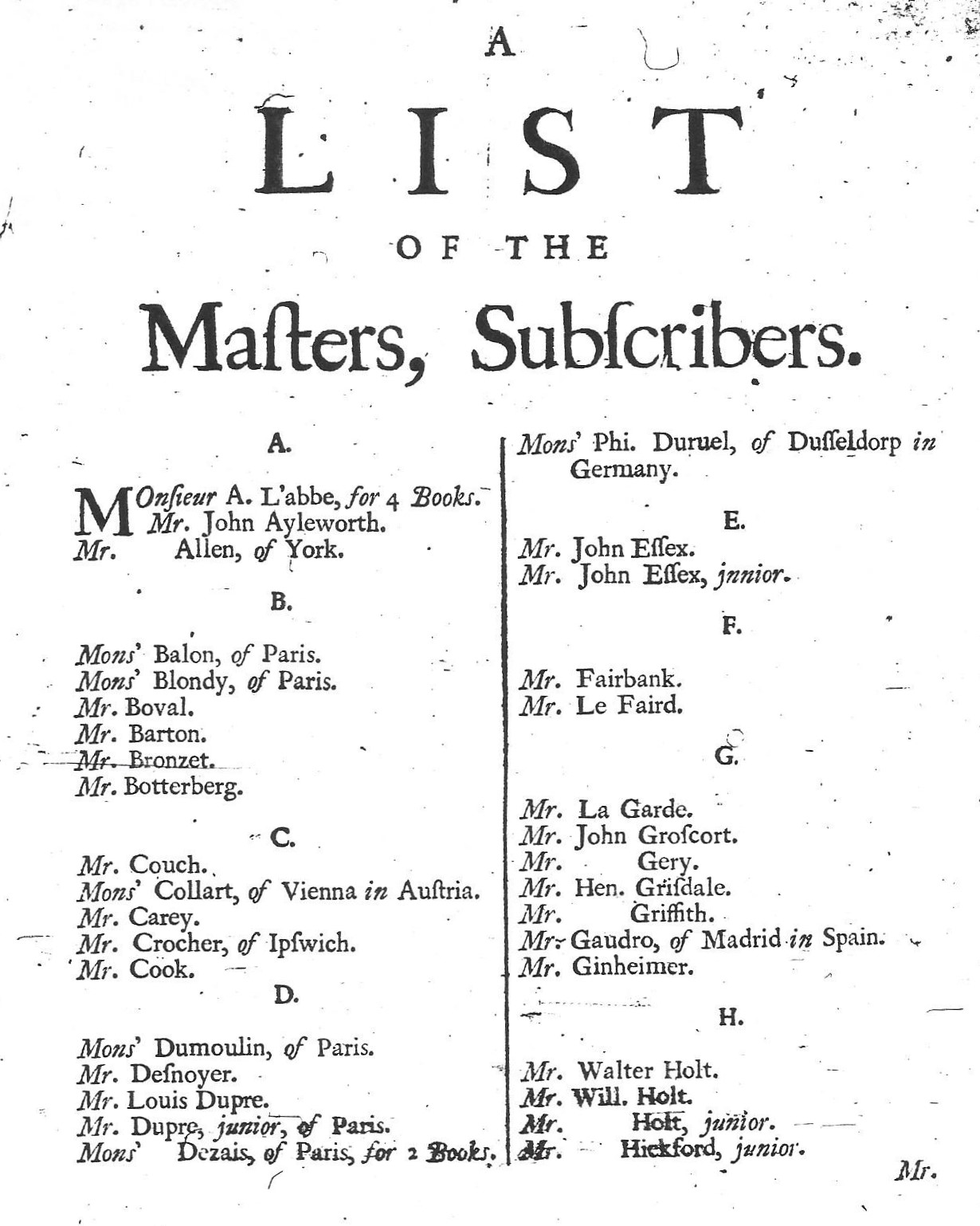

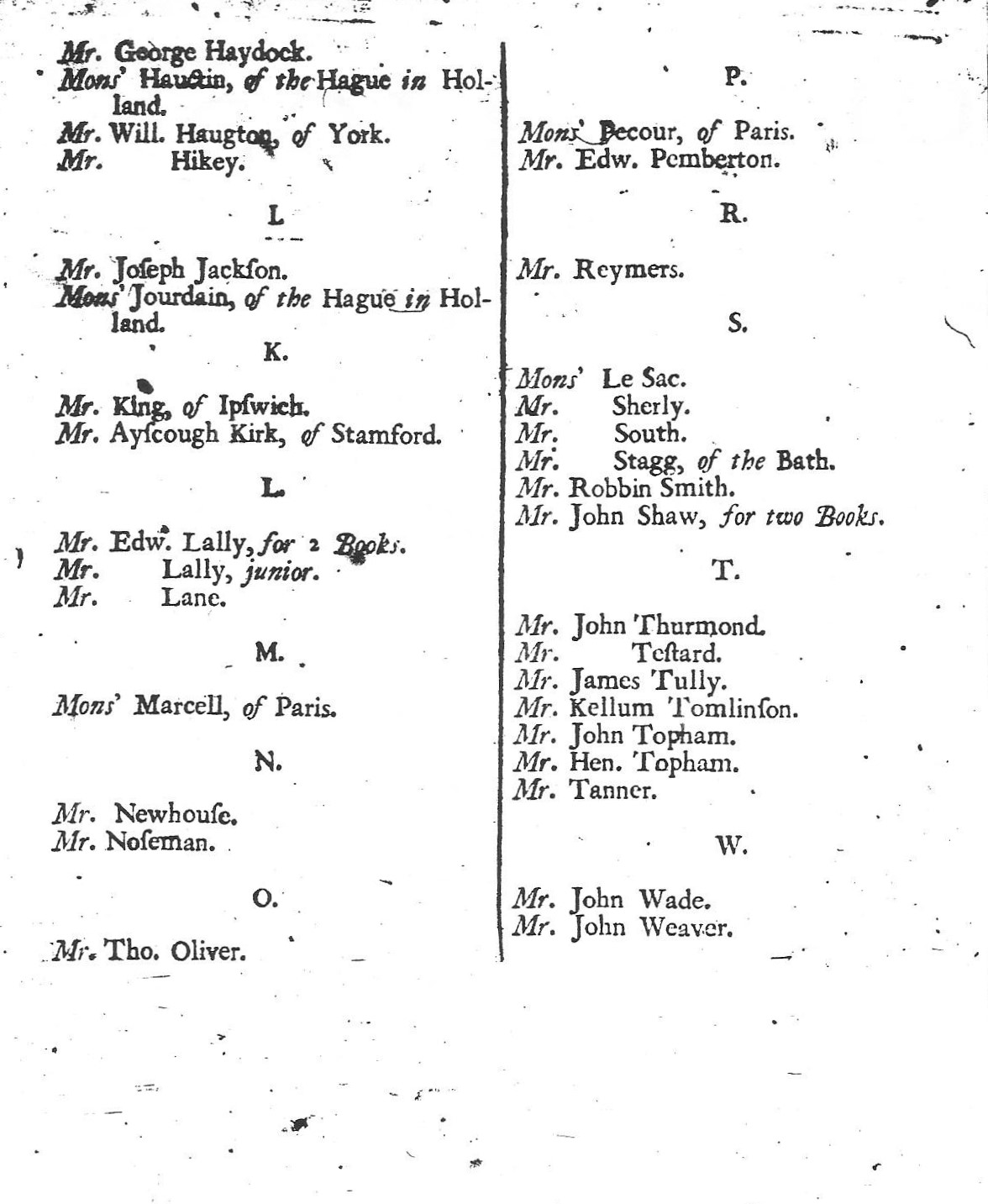

The list of subscribers is on two preliminary pages and has 68 names.

All five of the male dancers represented among the notated choreographies subscribed, but not one of the women – there are no female subscribers to this collection. Given the popularity with audiences of the professional female dancers named on the title page, that absence is worth further investigation. Was it to do with their status within the dance worlds of Britain, France and Europe? Was it that they didn’t teach (or weren’t known as teachers, even if they did)? Were they excluded from learning and using Beauchamp-Feuillet notation? I can’t readily answer any of those questions, but this subscription list reveals the need for a great deal more research and much discussion about the 18th-century dance world.

Of the 68 male subscribers, 48 were British and apparently based in London, six were from English provincial towns and cities, seven were French and five were based elsewhere in Europe. L’Abbé himself subscribed for four copies, while Dezais (Feuillet’s successor as the publisher of notated dances in Paris) took two – the same as Edward Lally (who may have been the seasoned dancing master Edmund Lally, rather than the young Edward Lally – probably his son – just beginning to make a name for himself on the London stage), and John Shaw who was one of London’s leading professional dancers. Shaw died young in December 1725, providing an end date for the publication of L’Abbé’s Collection. It is interesting that, although he had been trained by the French dancer René Cherrier and assuredly had a mastery of French dance style and technique, Shaw was not one of the Collection’s male dancers. They were all French, by ancestry if not nationality. Even more interesting is the fact that all the female dancers were British.

The list of subscribers includes ‘Mr. Edw. Pemberton’, probably Edmund Pemberton, the notator and publisher of L’Abbé’s ballroom dances many of which were created for the Hanoverian court to which L’Abbé was dancing master. L’Abbé’s list overlaps with that of Pemberton’s 1711 An Essay for the Further Improvement of Dancing (which includes a solo version of L’Abbé’s passacaille to music from Lully’s opera Armide). Pemberton’s dedicatee Thomas Caverley did not subscribe to L’Abbé’s theatrical choreographies, perhaps because – although he was a champion of dance notation – he was dedicated to the teaching of amateurs and ballroom dancing. Among the other English dancing masters who were L’Abbé’s subscribers were Couch, Essex, Fairbank, Groscourt, Gery, two members of the Holt family, Shirley and John Weaver. All supported both Pemberton’s and L’Abbé’s collections.

A handful of London’s other male professional dancers also subscribed – Boval, Newhouse, John Thurmond and John Topham, who were to be seen dancing varied repertoires at Drury Lane and Lincoln’s Inn Fields. We don’t know how much it cost to purchase L’Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances by subscription, but Le Roussau’s title page advertised copies at 25 shillings (around £145 today). Was this within the means of such dancers, some of who were definitely below the top ranks? Was their interest in the notations chiefly to aid teaching, or might they have drawn upon these when creating new choreographies for their own use?

John Weaver had been the first London dancing master to publish by subscription, with Orchesography (his translation of Feuillet’s Choregraphie) in 1706. Among the subscribers to L’Abbé’s Collection several had subscribed to one or more of the three works published in that way by Weaver (the others were A Collection of Ball-Dances by Mr Isaac, also in 1706, and Anatomical and Mechanical Lectures upon Dancing in 1721). A few – Essex, Walter Holt and Pemberton – subscribed to all five of the treatises published by subscription between 1706 and 1735. The last to appear was Kellom Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing, which he must have been planning if not writing close to the time when L’Abbé’s Collection was published, to which he subscribed.

Apart from a few continental dancers working in London’s theatres, there were no European subscribers to any of the dance treatises published in London – except for L’Abbé’s Collection, which had seven subscribers from Paris and five from elsewhere in Europe. Among the Parisians, I have already mentioned Dezais. His name is the only one that would be unfamiliar to non-specialists with an interest in dancing during the 18th century. Claude Ballon and Michel Blondy were close contemporaries of L’Abbé, as well as being leading dancers at the Paris Opéra from the 1690s and distinguished teachers of dancing. Ballon’s ballroom dances were published by Dezais. Dumoulin may well be David Dumoulin, the most celebrated of the four brothers who all pursued dancing careers at the Paris Opéra. He was noted for his mastery of the serious style. Like François Marcel, he was from a younger generation of dancers. He made his Opéra debut in 1705 followed by Marcel in 1708. Marcel was also making a reputation as a teacher. It is very unlikely that ‘Mr. Dupre, junior, of Paris’ was Louis ‘le grand’ Dupré, in fact he may have been related to London’s Louis Dupré the dancer in four of L’Abbé’s choreographies in the Collection.

The ’Mons. Pecour’ listed must have been Guillaume-Louis Pecour, ballet master at the Paris Opéra. His dancing career reached back to the early 1670s. L’Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances emulates the Nouveau Recüeil de Dance de Bal at Celle de Ballet notated and published by Gaudrau around 1713. Gaudrau’s collection of Pecour’s ballroom and stage choreographies has nine ballroom dances and thirty theatrical dances, to Le Roussau’s thirteen stage dances by L’Abbé. Gaudrau, ‘Mr. Gaudro, of Madrid in Spain’ is among L’Abbé’s subscribers. There is also ‘Mons’ Phi. Duruel, of Dusseldorp in Germany’ – John-Philippe Du Ruel had danced in London between 1703, when he was billed as ‘from the opera at Paris’ and described as a ‘Scholar’ of Pecour, and 1707, the year he danced at court for Queen Anne’s birthday celebrations. It seems likely that he was the dancing master based in Dusseldorf by the mid-1720s.

The subscription list to A New Collection of Dances surely represents L’Abbé’s own circle of dancers and dancing masters – those he knew and who knew him and his work. There were the men L’Abbé must have danced alongside at the Paris Opéra, as well as those he had worked with both onstage and off over the twenty years and more that he had been in London. What about the English provincial dancing masters and those in Europe? Did they know L’Abbé or did he know them, by reputation at least? Were they invited to subscribe and by whom? Did some of those who were more closely associated with L’Abbé act as intermediaries in this process? As you can see, I have rather more questions than answers about this particular list of subscribers.