At the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre, the manager John Rich had been watching Drury Lane’s developing repertoire of pantomimes and he was quick to respond to the success of Harlequin Dotor Faustus. On 20 November 1723, the afterpiece at Lincoln’s Inn Fields was ‘A New Dramatick Entertainment in Grotesque Characters’ entitled The Necromancer; or, Harlequin Doctor Faustus. Here is the advertisement from the Daily Courant that same day.

Rich himself, under his stage name ‘Lun’, took the title role. The new pantomime was given 51 performances before the end of the season and then played every season until 1744-1745. It was briefly revived in 1751-1752 and 1752-1753 before it finally disappeared from the repertoire.

The Necromancer was far more successful than Thurmond Junor’s Harlequin Doctor Faustus. It is thus interesting to note that in 1766-1767 Henry Woodward (who had been trained in the role of Harlequin by John Rich) produced a new pantomime at the Covent Garden Theatre titling it simply Harlequin Doctor Faustus. The advertisements declared that it drew on The Necromancer for some of its scenes, but it seems to have had little or nothing to do with Thurmond Junior’s original.

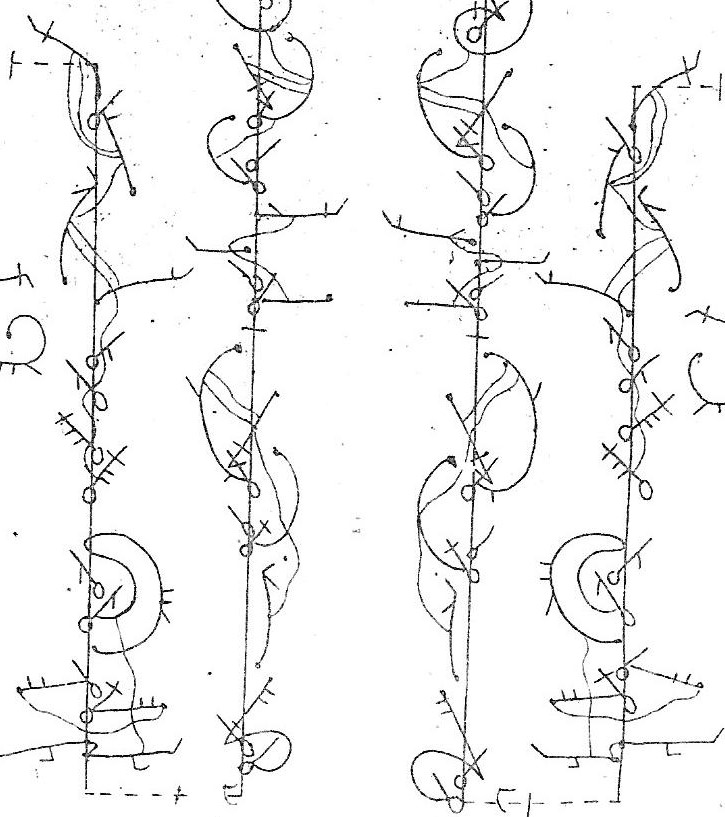

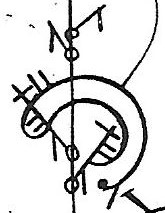

Rich’s pantomimes made much use of singing and The Necromancer had two scenes which exploited the talents of the singers in his company. The opening scene echoed that of Harlequin Doctor Faustus, as the Doctor is persuaded to sign away his soul, but Rich had a Good Spirit, a Bad Spirit and (instead of Mephostophilus) an Infernal Spirit, all of whom made their entreaties in song. A drawing now in the British Museum shows Faustus together with the Infernal Spirit in this scene.

There is a dance of five Furies in this same scene (which may have been a nod to French opera, which was a strong influence on Rich and his pantomime productions). The Infernal Spirit finally induces Faustus to take his fatal step by conjuring the appearance of Helen of Troy, who does not dance but sings. Rich’s creative response to his rival’s scenario can be seen from the very beginning of The Necromancer. The second episode of singing begins the final scene of the pantomime, when Faustus himself conjures Hero and Leander, who celebrate in song their eternal bliss in the Elysian Fields until Charon arrives and declares (again in song) his intention to ferry them to Hell.

The Lincoln’s Inn Fields pantomime was far more focussed than its rival at Drury Lane. It had only eight scenes, three of which were purely transitional – as characters entered and left the stage linking the scenes before and after with the minimum of action, a device that Thurmond Junior did not really use. The whole action of The Necromancer was published in An Exact Description of the Two Fam’d Entertainments of Harlequin Doctor Faustus … and The Necromancer of 1724. The first performances of the pantomime were accompanied by The Vocal Parts of an Entertainment, call’d The Necromancer : or, Harlequin Doctor Faustus which must have appeared before the end of 1723. There was also a series of editions of A Dramatick Entertainment call’d The Necromancer: or, Harlequin Doctor Faustus which gave only the sung texts. Without An Exact Description, we would know little about the comic action in The Necromancer.

There was dancing in five of the eight scenes. In scene 5, two men enter as Faustus is enjoying a meal with two Country Girls. He tells the men’s fortunes, which they reject and then try to make off without paying him. As they leave, Faustus ‘brings ‘em back on their Hands, making ‘em in that Posture dance a Minuet round the Room’.

In the following scene the dancing was probably more conventional, for the location moves to a Mill where the Miller’s Wife dances a solo before she is joined by the Miller for a duet. Their choreography may have owed something to the various Miller’s dances which had been given in the entr’actes at London’s theatres since the early 1700s. The scene carried on with one of the pantomime’s more daring scenic tricks, as Faustus tries to elude the Miller and make off with his wife, finally fixing the Miller to one of the sails of his own Mill and setting them turning.

Rich’s masterstroke was the finale of The Necromancer, which may have been developed in response to little more than a hint in Thurmond Junior’s Harlequin Doctor Faustus. In the latter, Mephostophilus ‘flies down upon a Dragon’ in the first scene, but Rich reserved the appearance of his monster to the end of his pantomime. As soon as Hero, Leander and Charon have vanished:

‘The Doctor waves his Wand, and the Scene changes to a Wood; a monstrous Dragon appears, and descends about half way down the Stage, and from each Claw drops a Daemon, representing divers grotesque Figures, viz. Harlequin, Punch, Scaramouch, and Mezzetin. Four Female Spirits rise in Character to each Figure, and join in an Antick Dance;’

This was probably the most substantial sequence of dancing in the pantomime, performed by the company’s leading dancers with Dupré and Mrs Rogier as the Harlequins, Nivelon Junior and Mrs Cross as the Pierrots (Punch is not listed among these dancing Spirits in the advertisements although he did appear in the pantomime, played by Nivelon Senior i.e. Francis Nivelon), Glover and Mrs Wall as the Mezzetins and Lanyon and Mrs Bullock as Scaramouches. Dupré was, of course, a dancing Harlequin and his performance in this last scene must have been very different from John Rich’s in the title role. The dance historian Richard Semmens has suggested that this ‘Antick Dance’ was performed to a chacone, a piece which is included among music for The Necromancer published some years later. The scene then moves inexorably to its tragic conclusion.

‘as they are performing, a Clock strikes; the Doctor is seiz’d by Spirits, and thrown into the Dragon’s Mouth, which opens and shuts several times, ‘till he has swallow’d the Doctor down, belching out Flames of Fire, and roaring in a horrible Manner. The Dragon rises slowly; the four Daemons that drop from his Claws, take hold of ‘em again, and rise with it; the Spirits vanish;’

Rich did not bother with a masque to point the moral of his tale. The Necromancer ends with a sung chorus:

Now triumph Hell, and Fiends be gay,

The Sorc’rer is become our Prey.

In contrast to Harlequin Doctor Faustus, evil apparently triumphs at the end of The Necromancer.

It has been suggested that Rich was preparing The Necromancer as a new pantomime for Lincoln’s Inn Fields well before Drury Lane mounted Harlequin Doctor Faustus, but the coincidence seems unlikely and does not fit with his later practice. Could he instead have been developing another theme and then quickly repurposed its tricks and transformations to outdo Drury Lane with its own story?

References:

Richard Semmens, Studies in the English Pantomime, 1712-1733 (Hillsdale, NY, 2016), chapter 3.

Olive Baldwin and Thelma Wilson, ‘“Heathen Gods and Heroes”: Singers and John Rich’s Pantomimes at Lincoln’s Inn Fields’, “The Stage’s Glory” John Rich, 1692-1761, ed. Berta Joncus and Jeremy Barlow (Newark, NJ, 2011), 157-168.