How many people (including dance historians) have heard of the pantomime Harlequin Doctor Faustus, which celebrates its 300th birthday this year? It wasn’t the first English pantomime but it began a craze for these afterpieces which established this unique genre of entertainment on the London stage.

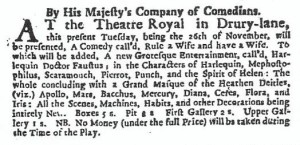

John Thurmond Junior’s Harlequin Doctor Faustus was first given at the Drury Lane Theatre on 26 November 1723. Here is the advertisement in the Daily Courant that same day:

It reveals the importance of commedia dell’arte characters, from Harlequin to Punch, as well as those from classical mythology, as part of its appeal to audiences. The emphasis on ‘Scenes, Machines, Habits and other Decorations’, all of which were ‘intirely New’ reveals the hopes of Drury Lane’s managers that the afterpiece would prove a money spinner. These were justified, at least for a while, for Harlequin Doctor Faustus was performed forty times before the end of 1723-1724 and was revived every season until 1730-1731. Its subsequent disappearance from the Drury Lane repertoire was probably due to the actors’ rebellion at the theatre at the end of the 1732-1733 season and the ensuing instability of the company. Harlequin Doctor Faustus was revived for eight performances in 1733-1734 but then disappeared altogether.

John Thurmond Junior was the son of the actor John Thurmond (hence his epithet) and seems to have begun his career on the Dublin stage. As a dancer, his repertoire ranged from the serious through the comic to the grotesque. His commedia dell’arte character was Scaramouch and he created the role of Mephostophilus in Harlequin Doctor Faustus. Thurmond Junior created several pantomimes for Drury Lane, notably Apollo and Daphne; or, Harlequin Mercury (first given on 20 February 1725) in which he used the serious part (with the title roles played by dancers – himself and Mrs Booth) to emulate John Weaver’s dramatic entertainments of dancing.

Harlequin Doctor Faustus and John Rich’s The Necromancer; or, Harlequin Doctor Faustus (first performed less than a month later, which I will also write about), Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre’s answer to Drury Lane’s pantomime, were so successful that scenarios for both were quickly printed. There are at least four different published versions of Harlequin Doctor Faustus, the most detailed of which brings both pantomimes together in print and probably appeared in 1724. Here is the title page:

This sets down the action in sixteen successive scenes, beginning in ‘The Doctor’s Study’ where Faustus signs away his soul and Mephostophilus ‘flies down upon a Dragon, which throws from its Mouth and Nostrils Flames of Fire’ to take the contract from him and present him with a white wand ‘by which he has the Gift and Power of Enchantment’. The following scenes present a frenzy of action with many tricks and transformations as well as a generous scattering of dances. Faustus was performed by John Shaw, whose formidable dance talents encompassed a wide range of styles (I have mentioned him in a number of previous posts).

The fourth scene turns to classical literature. Faustus and three ‘Students’ (in the characters of Scaramouch, Punch and Pierot) are drinking together when the table at which they are sitting:

‘… upon the Doctor’s waving his Wand, rises by degrees, and forms a stately Canopy, under which is discover’d the Spirit of Helen, who gets up and dances; and on her return to her Seat, the Canopy gradually falls, and is a Table again.’

‘Helen’ is, of course, Helen of Troy. Scene fourteen ends with a scenic spectacle as Doctor Faustus and his companions try to escape a pursuing mob by locking themselves into a barn. When the mob force a way in, they escape down the chimney ‘but the Doctor, as he quits the Barn-Top, waves his Wand and sets it all on Fire; it burns some time, very fiercely, and the Top at last falling in, the Mob, in utmost Dread, scour away’.

Scene fifteen returns to the Doctor’s study as his agreement with the Devil expires and he is accosted first by Time and then by Death, who strikes Faustus down.

‘Then two Fiends enter, in Lightning and Thunder, and laying hold of the Doctor, turn him on his Head, and so sink downwards with him, through Flames, that from below blaze up in a dreadful Manner; other Dæmons, at the same Time, as he is going down, tear him Limb from Limb, and, with his mangled Pieces, fly rejoicing upwards.’

Thurmond Junior’s pantomime did not end there, for a final scene revealed ‘A Poetical Heaven. The Prospect terminating in plain Clouds’ in which ‘several Gods and Goddesses are discover’d ranged on each Side, expressing the utmost Satisfaction at the Doctor’s Fall’. They perform a series of dances, beginning with a duet by Flora and Iris, then a ‘Pyrrhic’ solo by Mars (danced by Thurmond Junior), a duet by Bacchus and Ceres, followed by a solo for Mercury (danced by John Shaw) ‘compos’d of the several Attitudes belonging to the Character’. This ‘Grand Masque of the Heathen Deities’ was a divertissement of serious dancing and culminated as ‘the Cloud that finishes the Prospect flies up, and discovers a further View of a glorious transcendent Coelum’ revealing:

‘Diana, standing, in a fix’d Posture on an Altitude form’d by Clouds, the Moon transparent over her Head in an Azure Sky, tinctur’d with little Stars, she descends to a Symphony of Flutes; and having deliver’d her Bow and Quiver to two attending Deities, she dances.’

Diana was performed by Hester Booth, the leading dancer on the London stage. The newspapers were dismissive of the comic scenes in Harlequin Doctor Faustus, but they were agreed on the magnificence of the concluding masque and the beauty of Mrs Booth’s dancing. Both the comic and the serious parts of Thurmond Junior’s pantomime would influence many future productions.

It is frustrating that we have next to no evidence of this or most other 18th-century pantomimes. There are no records of costumes or scenery and such music as seems to survive may, or may not, belong to this production. No portrait of John Thurmond Junior is known. The nearest we can get is the satirical engraving ‘A Just View of the British Stage’ which castigates the Drury Lane management for their pantomime productions. Thurmond Junior may be the dancing master (identifiable by his pochette) shown hanging towards the top right of the print.

References:

Moira Goff, ‘John Thurmond Junior – John Weaver’s Successor?’, Proceedings, Society of Dance History Scholars, Twenty-Sixth Annual Conference, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland, 26-29 June 2003 (Stoughton, Wisconsin, 2003), pp, 40-44.

Moira Goff, The Incomparable Hester Santlow (Aldershot, 2007), pp. 115-117.

Richard Semmens, Studies in the English Pantomime, 1712-1733 (Hillsdale, NY, 2016), chapter 2