Mr Isaac’s The Richmond was first published in notation in 1706 in A Collection of Ball-Dances Perform’d at Court.

The dance is named first on the title page, probably because the collection was dedicated to the Duke of Richmond, and it seems most likely that the title of the dance was meant as a tribute to him. It may well have been one of the dances that John Weaver (who notated the collection) declared in his dedication to ‘have been Honour’d with your Grace’s Performance’.

The American dance historian Carol Marsh, in her 1985 thesis ‘French Court Dance in England, 1706-1740’, suggested that the choreography dated to more than ten years earlier. As she pointed out, the music was published in The Self-Instructor on the Violin, advertised for publication on 15 July 1695. The duet could perhaps have been performed at the ball held at Whitehall Palace on 4 November 1694 to celebrate the birthday of King William III. The Duke of Richmond, son of Charles II and Louise de Keroualle the Duchess of Portsmouth, had initially been opposed to the changes wrought by the Glorious Revolution. He was reconciled with William III in 1692 and in January 1693 he married Anne Belasyse. He might well have performed The Richmond if and when it was performed at court. This portrait by Godfrey Kneller shows the Duke some ten years after The Richmond may have been created.

The Richmond is a hornpipe in 3/2, often described as a specifically ‘English’ dance and occasionally said to have pastoral connotations. It is distinct from the later duple-time hornpipe often associated with sailors. The dance type was evidently a favourite with Mr Isaac, who also used it in The Union (1707), The Royall (1711) and The Pastorall (1713). Anthony L’Abbé, who became royal dancing master around 1715, included a hornpipe in The Princess Ann’s Chacone (1719) and used the music from Isaac’s The Pastorall for a stage solo for a man, published in notation around 1725 but possibly performed the same year as Isaac’s ballroom duet. He may have been paying tribute to Isaac, who was also his brother-in-law.

This earlier form of hornpipe has attracted the attention of several dance historians (a number of references are given at the end of this post), who between them have noted that hornpipe music first emerges in the 1650s and that it was a dance type that appealed to Purcell, among other late 17th century composers, as well as investigating the characteristic steps of the dance. Purcell was certainly including triple-time hornpipes in his stage music by the 1690s. Among modern historical dance enthusiasts, there is particular interest in the hornpipes included within editions of Playford’s The Dancing Master, under the titles ‘Maggot’, ‘Delight’ or ‘Whim’ – ‘Mr Isaac’s Maggot’ appears in the 9th edition of 1695 – although, sadly, there seems to be little enthusiasm for the exploration of some of the hornpipe pas composés described below (I can’t help thinking that some of the fun in such dances must have been the steps). Triple-time hornpipes continued to be used for dances into the early decades of the 18th century. Fresh research is certainly needed to chart the emergence, rise and decline of this version of the hornpipe within a variety of dance contexts.

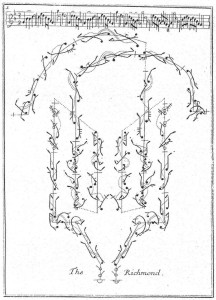

My interest here is, of course, the hornpipes within the notated ball dances – in my time, I have had the pleasure of dancing The Richmond, The Union, The Pastorall and The Princess Ann’s Chacone. Only The Richmond is a hornpipe throughout, the other dances pair it with different dance types. The musical structure of The Richmond is more complex than usual for ballroom dances – AABBCCDDEEFF’ (A = B = C = D = E = 4, F=8, F’ = 4) with 52 bars of music in all. The division of the choreography between the six plates of the notation seems to be pragmatic in terms of the steps and figures to be recorded rather than reflecting the musical structure.

As I noted in an earlier post, the opening figure of The Richmond is unorthodox.

The couple travel forwards away from each other on a diagonal before turning inwards to face each other. They turn to face the presence on bar 3, but maintain that orientation for only two bars before turning to face one another again for one bar, after which they turn to face the presence on bar 6. Their steps in the opening figures are rhythmically varied and two-thirds include pas sautés, an indication of the lively nature of this hornpipe.

Mr Isaac’s hornpipes have a distinctive vocabulary of steps. A particular characteristic is his use of three pas composés over two bars of music, found throughout The Richmond. This may take a form in which the same step begins and ends the sequence with two other steps between them (performed on either side of the bar line) which may or may not be the same. One example is found on plate 1 in the opening bars in the form pas de bourrée, saut / jetté, pas de bourrée, while another can be found on plate 2 as pas de bourrée, jetté / jetté, pas de bourrée. In the second case the first step is actually a pas de bourrée vîte, while the second step is a variant which inverts its two elements. In other cases, Isaac begins and ends the sequence with different steps but still has paired steps on either side of the bar line, as on plate 1 with a contretemps, jetté / jetté, pas de bourrée imparfait (i.e. to point). Or, as yet another variation, the sequence may divide a familiar pas composé at the bar line, as an example on plate 2 demonstrates with pas de sissonne, pas de sissonne, pas de bourrée, in which the second pas de sissonne begins in the first bar with its pas assemblé and ends in the second bar with its sissonne. In The Richmond, Isaac is endlessly inventive with this device.

The Richmond is one of the choreographies in which Isaac ornaments some of the man’s steps but not the woman’s. Although, among the six dances published in 1706, only The Spanheim and The Britannia are without such ornamentation. Throughout the dance, there are five bars where this happens and in all cases a pas battu is added on the man’s side. On plate 5 this ornamentation is added in two consecutive bars and coincides with a change from mirror to co-axial symmetry.

Isaac also ornaments the man’s steps right at the end of the dance, altering his sequence of pas composés. Over the final two bars, the woman has coupé emboîté battu, demi- contretemps / jetté, coupé simple, coupé soutenu (with a half-turn into a réverence). The man has coupé emboîté battu, demi-contretemps battu / contretemps à deux mouvements battu, coupé soutenu (the last is his réverence). She turns to travel forwards, while he turns to travel backwards. They do not take hands for these last steps, although they had done so for preceding bars.

There are more linear than circular figures in The Richmond, although Isaac makes effective use of the latter on plates 2 and 6. The relationship between the two dancers and between them and their audience is interesting. If this dance was performed at a formal ball, the couple would probably have had the presence (the King?) in the place of honour centre front as well as an audience of courtiers surrounding them on the other three sides. So where would they have looked as they danced? Plate 1 shows them dividing their attention between the presence and each other. In the first two bars on plate 3, they clearly address the spectators on each side (and at the bottom of the room) before turning towards one another to dance on a right line. There are similar opportunities on plate 5, although the couple are otherwise dancing beside one another and facing the presence.

Working again on this dance, after a gap of many years, I couldn’t help wondering if the arm movements might have been as unconventional as the steps and whether the dancers could direct their lines of vision quite freely as they moved, enabling them to acknowledge not just each other and the presence, but also the encircling audience.

My recent work has raised several questions about the performance of The Richmond and the other dances in the 1706 Collection. The title page states that they were ‘perform’d at court’, but what did this mean? Were they danced as part of a formal display, either at birth night balls or on other such occasions? Were they instead danced at one of the more informal balls at the English court? In his ‘Livre de la contredance du roy’, presented to Louis XIV in 1688 and retranscribed for Louis XV in 1721, André Lorin wrote:

‘Cette cour [the English royal court] divise ces divertissements en Bals serieux, et en Bals ordinaires.

Les serieux se dançent toujours dans un Lieu preparé, ou toute la Cour paroit superbe et magnifique.

Les ordinaires regardent les Contredances qu’on dance avec plus de negligence et dans les apartemens du Roy, où l’on ne va qu’avec les habits ordinaires, afin de dancer avec plus de liberté: …’

The manuscript is now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and can be found on Gallica. Lorin was concerned with English country dances, but could the ‘Bals ordinaires’ have included couple dances like The Richmond? Or, if they were indeed given at ‘Bals serieux’, should we think again about the conventions governing the dance displays at such events?

Further reading:

George S. Emmerson, A social history of Scottish dance (Montreal, 1972), chapter 14

The Hornpipe: papers from a conference held at Sutton House, Homerton, London E9 6QJ, Saturday 20th March 1993 (Cambridge, 1993)

Carol G. Marsh, ‘French court dance in England, 1706-1740: a study of the sources’ (PhD thesis, City University of New York, 1985), pp. 243-258.

Barbara Segal, ‘The Hornpipe: a dance for kings, commoners and comedians’, Kings and commoners: dances of display for court, city and country. proceedings of the seventh DHDS conference, 28-29 March 2009 (Berkhamsted, 2010), 33-44

Linda J. Tomko, ‘Issues of Nation in Isaac’s The Union’, Dance Research, XV.2 (Winter 1997), 99-125.

The Richmond is also mentioned in the following posts on Dance in History:

Mr Isaac’s Six Dances

Mr Isaac’s Choreography: The Six Dances – Opening and Closing Figures

Mr Isaac’s Choreography: The Six Dances – Motifs and Steps