I am pursuing a line of research that has led me to the entrée grave and its use in musical works on the London stage in the late 17th century, so I thought I would take a closer look at this dance type through the choreographies surviving in notation. I have, of course, written about male dancing in other posts and I list these below for anyone who might be interested.

In her 2016 book Dance and Drama in French Baroque Opera (p. 56), Rebecca Harris-Warrick describes the entrée grave as ‘a slow dance in duple meter characterized by dotted quarter note /eighth-note patterns, rather like the opening portion of an overture’, cautioning that ‘“grave” is found in the headings for choreographies … in scores such a piece is generally identified simply as an entrée or an air’. She also tells us that ‘in choreographic sources entrées graves are always danced by men’ (although she does cite an opera in which one may have been danced by women, p. 332).

Here, I am concerned only with the ‘choreographic sources’, as I want mainly to look at the vocabulary and technique associated with the entrée grave. The most comprehensive listing of notated dances is provided by La Danse Noble by Meredith Little and Carol Marsh, published in 1992, which includes an ‘Index to Dance Types and Styles’. The authors point out that ‘classification by type and style is often a problematic matter’ and this is certainly the case with the entrée grave. They list eight notated choreographies as entrées graves, but Francine Lancelot in La Belle Dance identifies only two in her ‘Index of Dances according to the Number of Performers’ – adding another six through her detailed descriptions of individual notations. I include references to entries in both of these catalogues in my list of choreographies below – prefaced LMC for Little and Marsh and FL for Lancelot.

The dances they identify as entrées graves are not quite the same. Little and Marsh include two solo versions of the ‘Entrée de Saturne’ from the Prologue to Lully’s Phaëton which are not this dance type (LMC4000 and LMC4260) and are not so identified by Lancelot (FL/1700.1/11 and FL/MS05.1/13). These are omitted from the list below. However, Lancelot identifies two male duets which are not classified as entrées graves by Little and Marsh (LMC4220, FL/1704.1/23 and LMC2780, FL/1713.2/36) which have been added to the list. So, between them, these two catalogues identify eight notated choreographies which may be classed as entrées graves. The dancing characters are identified by Lancelot from the livrets for the individual operas from which the music for the dance is taken.

Feuillet, Recüeil de dances (Paris, 1700)

- ‘Entrée grave pour homme’, music anonymous (AABBB’ A=8 B=9 B’=4 38 bars). No dancing character indicated. (LMC4140, FL/1700.1/13)

- ‘Entrée d’Apolon’, music from Lully Le Triomphe de l’Amour (1681), entrée XV (AABBB’ A=9 B=19 B’=7 63 bars). Dancing character Apollo. (LMC2720, FL/1700.1/14)

- ‘Balet de neuf danseurs’, opening section, music from Lully Bellérophon (1679), act V scene 3 (AABB A=B=11 44 bars). Dancing characters Lyciens. (LMC1320, FL/1700.1/15)

Pecour, Recüeil de dances (Paris, 1704)

- ‘Entrée pour deux hommes’, music from Lully Cadmus et Hermione (1674), V, 3 (AABB A=4 B=9 26 bars). Lancelot notes that the music is a gavotte but implies that the choreography is actually an entrée grave (as indicated by the notation). Dancing characters Suivants de Comus. (LMC4220, FL/1704.1/23)

- ‘Entrée d’Appolon pour homme’, music from Lully Le Triomphe de l’Amour (1681), entrée XV (AABBB’ A=9 B=19 B’=7 63 bars). Dancing character Apollo. (LMC2740, FL/1704.1/30)

Pecour, Nouveau Recüeil de dances (Paris, c1713)

- ‘Entrée de Cithe’ (a male duet), music from Bourgeois, Les Amours déguiséz (1713), 3e Entrée (AAB A=10 B=16 36 bars). Dancing characters Scithes (Scythians). (LMC2780, FL/1713.2/36)

- ‘Entré seul pour un homme’, music from Stuck Méléagre (1709), act II scene 7 (AABB A=8 B=13 42 bars). Dancing characters Guerriers. (LMC4580, FL/1713.2/38)

L’Abbé, A New Collection of Dances (London, c1725)

- ‘Entrée’, music from Lully, Acis et Galatée (1686), Prologue (AABB A-10 B=13 46 bars). Dancing characters in the opera Suite de l’Abondance, Suite de Comus. (LMC4180, FL/1725.1/12)

So, we have in all six male solos and two male duets published over the first quarter of the 18th century that might tell us something about the step vocabulary and the dance style of the entrée grave. The details given above provide quite a lot of information, before we turn to the notations themselves. All the choreographies are quite short. The longest are the two versions, by Feuillet and Pecour respectively, of the ‘Entrée’ for Apollo to music from Lully’s Le Triomphe de l’Amour of 1681, with 63 bars of music. The shortest is Pecour’s ‘Entrée pour deux hommes’ from Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione of 1674, with only 26 bars of music (and a question mark over the dance type it represents). It is worth remembering that, with the entrée grave, each bar of music has two pas composés of dancing many of which are complex or virtuosic. The music has to be slow to allow the dancers time to execute the steps.

None of Feuillet’s choreographies and none of Pecour’s solos are directly linked with performances at the Paris Opéra. Indeed, Pecour’s version of the ‘Entrée d’Appolon’ states that it was ‘non dancée à l’Opera’. Only Pecour’s two duets record dances performed there – the dancers are named in the livrets for each opera as well as on the head-title for each notation. L’Abbé’s solo for Desnoyer was created for performance in London, as an entr’acte entertainment at the Drury Lane Theatre. Nevertheless, given that L’Abbé as well as Pecour had danced at the Paris Opéra and that Feuillet must also have been familiar with its repertoire as well as its dance conventions, it is worth considering the dancing characters for which the music was originally written as part of any choreographic analysis.

Apollo was, of course, the Olympian god identified with the sun (and with whom Louis XIV identified himself). The Lyciens were simply men of Lycia, celebrating the marriage of the Lycian princess Philonoé to the hero Bellérophon. The Suite (Followers) of Comus were the dancing characters in both Cadmus et Hermione and, probably, Acis et Galatée. The Cithes (Scythians), in other contexts known as warlike nomads from southern Russia, take part in celebrations in Les Amours déguiséz, but they also link to the Guerriers who dance an entrée grave in Méléagre. Between them, these characters carry three separate associations which might also overlap. Apollo represents power and control, yet there is an underlying hint of excess given the god’s many love affairs. The theme of revelry links the Followers of Comus with the Lyciens and the Cithes. The Guerriers, and perhaps the Cithes, suggest the portrayal of power and control. The messages conveyed by the entrée grave may be less clear and fixed than has been supposed.

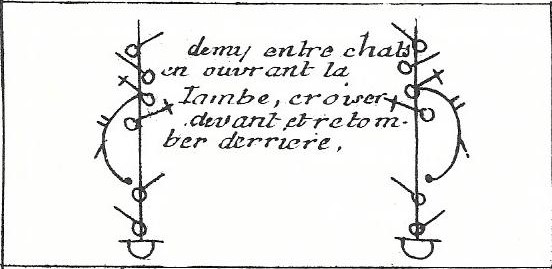

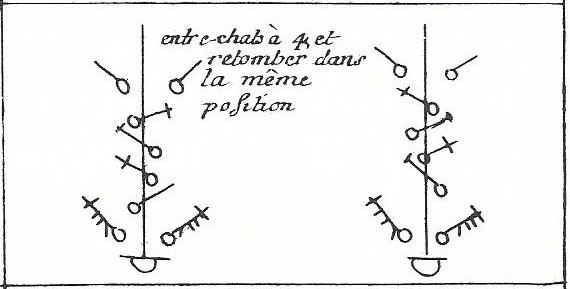

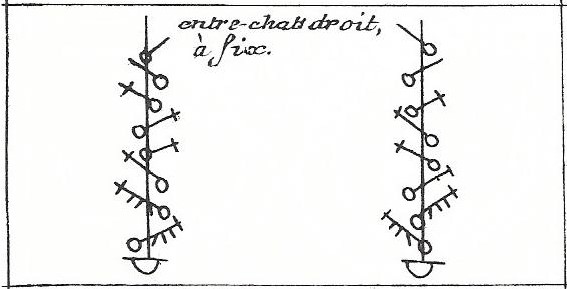

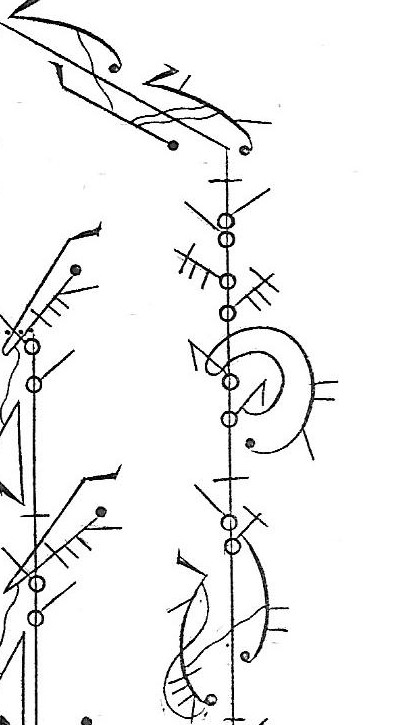

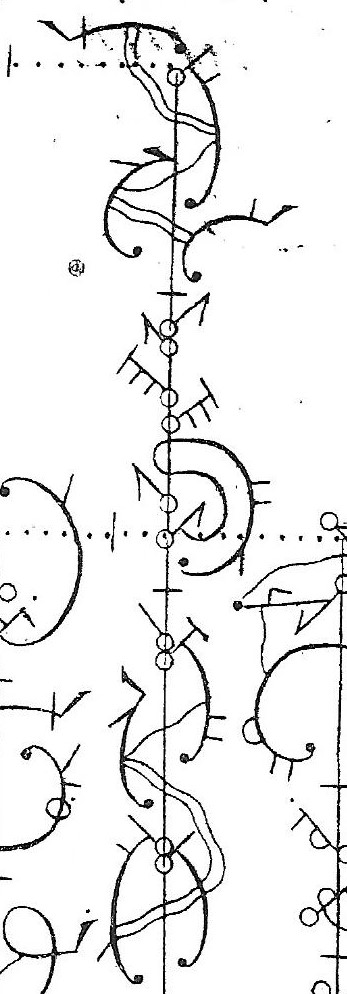

An analysis of the notated dances reveals shared features. They routinely include some of the most virtuosic male steps – multiple pirouettes (with and without pas battus by the working leg), entre-chats à six and a variety of cabrioles, in particular the demie cabriole en tournant un tour en saut de basque. The first plate of Pecour’s ‘Entrée d’Appolon’, published in 1704, shows both an entre-chat and the demie cabriole en tournant, while the third plate shows two pirouettes, one without and one with pas battus.

All of these entrée grave choreographies include a number of basic steps, between a quarter and a third of the total in the surviving notations. They also routinely ornament such steps with beats and turns, making them far more complex. Examples of both (with some unadorned basic steps) can be seen in the second plate of Feuillet’s ‘Entrée grave pour homme’ from his collection of 1700.

The figures (floor patterns) traced by these male dancers are not easy to interpret. They seem mainly to move downstage and upstage on a central line, with occasional steps to right or left which quickly bring them back centre stage. Many of their steps, particularly those classed as virtuosic, are performed in place, so the dancer does not travel nearly as much as the notations imply. (Steps are, of course, written along the dance tracts, whether or not the dancer travels along these). The few circular figures are usually associated with the demie cabriole en tournant un tour en saut de basque, which makes a turn in the air so that the dancer lands close to where he began his jump. There are a few video recordings of some of the notated entrées graves which show the dancers traversing the stage quite freely, but I am not sure how much these owe to the demands of the dancing space rather than the notation. These male solos are certainly more compact and less varied in their figures than the corresponding female theatrical solos.

The only entrée grave for more than one or two male dancers is the ‘Balet de neuf Danseurs’ by Feuillet, again from his 1700 collection. It is danced by a leading man with eight ‘Followers’ who stand behind and to each side of him as he begins the choreography. Only the first section is an entrée grave, which is followed by two canaries. The soloist dances the first A section and then stands centre back while four of the eight Followers (those who were standing behind him) perform two parallel duets to the second A section. The soloist then dances to the first B section and is followed by the same four men, who resume their duets for the second B section. The dance continues with the soloist, who dances the first and second canary, and it finishes with all eight Followers dancing the repeat of the two canary tunes while the soloist again stands centre back. This choreography may reveal one way in which dancing masters could deploy a group of male dancers onstage for an entrée grave. Here are the first two plates of this choreography.

There is one other entrée grave choreography that I have not so far mentioned, but which is equally relevant to the research project that brought me to this topic. This is the ‘Air des Ivrognes’ in Le Mariage de la Grosse Cathos, a ballet performed at the court of Louis XIV in 1688. The ballet was recorded by its choreographer Jean Favier in a dance notation of his own invention, which was published in facsimile, decoded, set in context and analysed by Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Carol G. Marsh in 1994 in Musical Theatre at the Court of Louis XIV. They suggest that this duet, performed by two male dancers from the Paris Opéra in the guise of Peasants, ‘would have been immediately recognised as a burlesque of the entrée grave, the noblest and most difficult of the theatrical dances of the time’ (p. 55). As their analysis reveals, it is indisputably a comic number even as the dancers attempt some of the virtuosic feats associated with this dance type.

My research into the entrée grave has, necessarily, been limited. It would be useful to know how many more entrées graves there are in the operas of Lully and his immediate successors and which characters performed them, even though the choreographies are lost, but this is a task for musicologists. Although much of my work on baroque dance is practical, the demands of the entrée grave are well beyond my dancing skills – it is a shame that conference papers by those who have danced these difficult choreographies should remain unpublished and thus inaccessible. I have been able to answer some of my own immediate research questions, but my work has uncovered others. Was the entrée grave simply an expression of power and nobility or did it have other contexts with different meanings? How well was this dance known beyond France and how was it seen and understood elsewhere, for example in London? What was it really like in performance?

Reading list:

Rebecca Harris-Warrick. Dance and Drama in French Baroque Opera (Cambridge, 2016)

Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Carol G. Marsh, Musical Theatre at the Court of Louis XIV: Le Mariage de la Grosse Cathos (Cambridge, 1994)

Francine Lancelot. La Belle Dance: Catalogue Raisonnée (Paris, 1996)

Meredith Ellis Little and Carol G. Marsh. La Danse Noble: an Inventory of Dances and Sources (Williamstown, 1992)

Previous Dance in History Posts about Male Dancing:

Money for Entrechats: Valuing the Virtuosic Male Dancer – L’Abbé and Ballon

Money for Entrechats: Valuing the Virtuosic Male Dancer – Delagarde and Dupré

Demie Cabriole en Tournant un Tour en Saut de Basque – a Step Solely for a Man?

Demies Cabrioles in Male Solos and Duets

Pas de Sissonne Battu in Stage Dances for Men

Entre-Chats in Male Solos and Duets