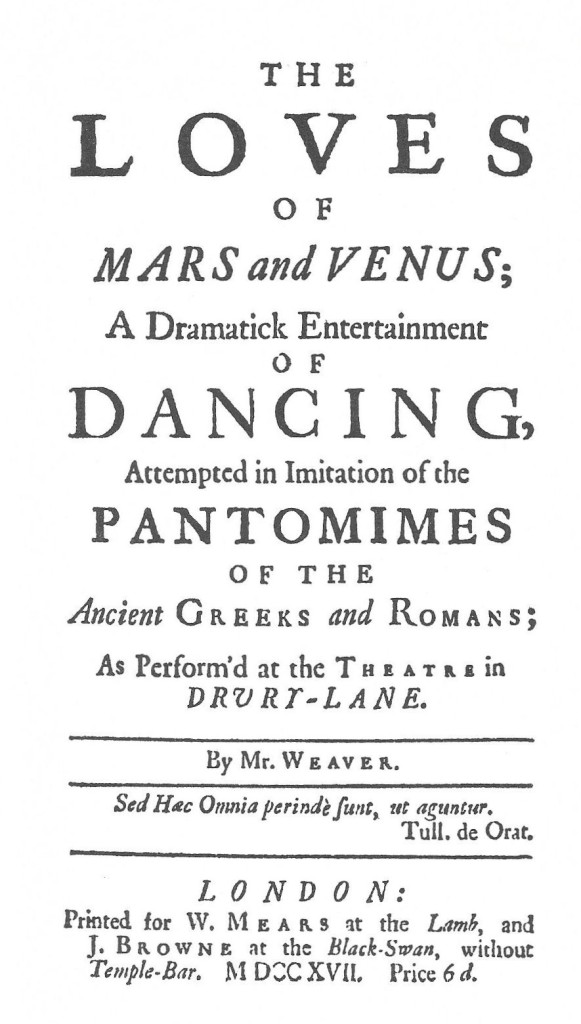

John Weaver’s innovative ‘Dramatick Entertainment of Dancing’ The Loves of Mars and Venus was first performed at the Drury Lane Theatre on 2 March 1717. The scenario for the afterpiece was published the same week, as announced in the Evening Post, 23-26 February 1717.

‘This Week will be published, as it will be perform’d at the Theatre in Drury Lane. The Loves of Mars and Venus, a Dramatick Entertainment of Dancing in Imitation of the Pantomimes of the ancient Greeks and Romans, compos’d by Mr. Weaver being a Description thereof, written by him for the Benefit of the Spectators, the Novelty of the Undertaking absolutely requiring some Instructions for the better [illustrating?] the same. Printed for W. Mears at the Lamb, and J. Brown at the Black Swan both without Temple-bar.’

This small work is the only surviving source for Weaver’s ballet and it is worth looking more closely at its publication history.

The scenario is the first work to describe in detail the action, dance and gesture in a ballet. It has been linked to the livrets published to accompany ballets at the French court in the late 17th century, but these works had little in the way of extended narrative and included songs which helped audiences to understand the action.

As the advertisement states, The Loves of Mars and Venus was printed for William Mears and J. Browne. Both were involved in the printing of plays and active in selling them. Mears also published opera libretti as well as masques and some early pantomime texts. The origins of Weaver’s scenario perhaps lie in such printed play texts and libretti for the Italian operas that were so popular in London. It was printed as an octavo – the same format as most plays in the early 18th century. The scenario was not ‘printed for the author’, so Weaver presumably sold his copyright to Mears and Browne and did not have to cover any of the printing costs. They were free to republish the text as and when they wished.

Weaver’s scenario is a pamphlet of just 24 pages. The imprint tells us that it cost 6d. (6 old pence), the same price as brief interludes or song texts. Mainpiece plays were 1s. 6d., reflecting their greater length. Although modern equivalents of 18th-century prices are difficult to calculate, 6d. was roughly £5 to £7.50 in today’s money. The size of the print run can only be guesswork, although 250 to 500 copies provide a reasonable estimate.

The relationship between the number of copies printed and audiences at performances of The Loves of Mars and Venus indicates that, even in its first season, very few spectators are likely to have been able to consult the scenario. Drury Lane held 800 to 1000, of whom around half were seated in the more expensive seats in the pit and boxes. We have no idea how many were in the audience at each of the seven performances of the afterpiece in 1716-1717. The advertisement says nothing about the scenario being available for purchase at the theatre, so would-be members of the audience would have needed to seek out a copy at the bookseller. On the other hand, the sale of the scenario elsewhere may have encouraged theatre-goers to attend Weaver’s experimental ballet.

There were more than forty performances of The Loves of Mars and Venus between 1716-1717 and 1723-1724 and another edition of the scenario was published by William Mears in 1724 to accompany the last revival of the afterpiece. This new edition was advertised in the Evening Post for 28-30 January 1724, a few days after the initial performance that season. It carries no edition statement and has the same internal pagination as the 1717 edition, so it may have been a reissue of unsold copies of the original edition. Unfortunately, I have not been able to examine a copy of the 1724 edition and there is no digital version which might allow me to check its status.

There was also an edition published in Dublin in 1720, which I would dearly like to see (according to the English Short Title Catalogue there is only one known copy, which is not accessible digitally). The Loves of Mars and Venus was never performed in Dublin, so far as we know, so this edition perhaps reflects the ballet’s success in London. Mears and Browne went on to publish the scenario for Weaver’s next ‘Dramatick Entertainment of Dancing’ Orpheus and Eurydice in 1718, which needs a post of its own.

The irregularity in the pagination of the 1717 scenario is worth investigating. The volume collates [A]2 B – C4 D2, which is not unusual, but the pagination runs [4], ix-xvi, 17-28. There seems to be a four-page gap, suggesting either an initial gathering of four leaves rather than two, or perhaps an additional two-leaf gathering after [A]. Was Weaver hoping to include a dedication, which did not materialise? In 1706, he had dedicated Orchesography (his translation of Feuillet’s Choregraphie) to Mr Isaac and his An Essay Towards an History of Dancing of 1712 to Thomas Caverley. Who might have been the intended recipient of The Loves of Mars and Venus? Did Weaver perhaps wish to dedicate the scenario to Sir Richard Steele, licensee and manager of the Drury Lane Theatre and also a playwright? Steele had apparently invited Weaver to return to Drury Lane to mount his ballet but may not have wanted to accept the dedication. Or did Weaver have an aristocratic or even a royal patron in mind, only to be disappointed at the last moment?

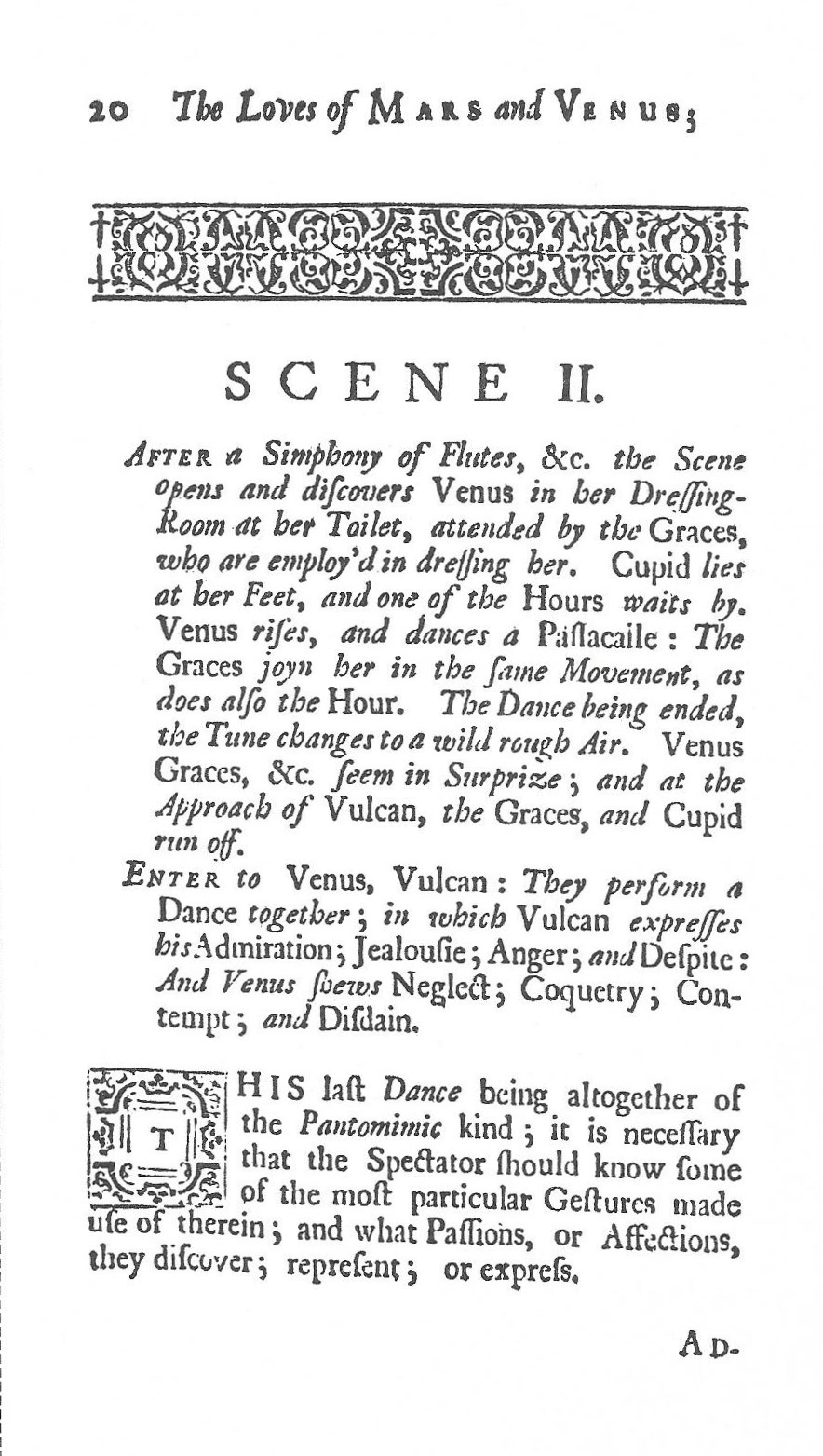

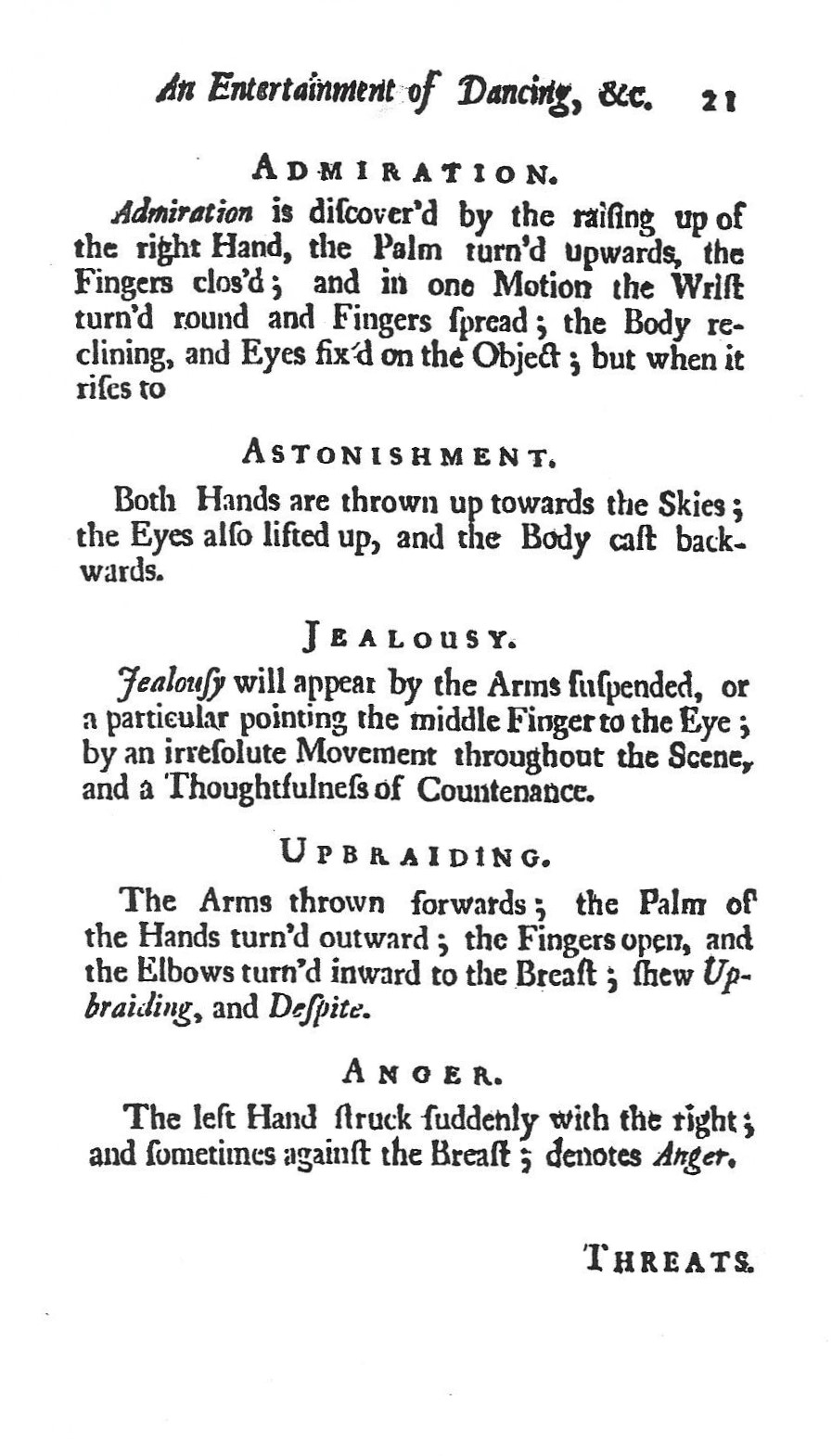

The scenario for The Loves of Mars and Venus has a Preface, in which Weaver explains his intention to introduce dancing ‘in Imitation of the Pantomimes of the Ancient Greeks and Romans’ to the London stage and apologises for the deficiencies in the performance of this ‘entirely novel’ form of entertainment. This is followed by a cast list, with mini-biographies of Mars, Vulcan and Venus. The action and the dancing in the afterpiece are divided into six scenes and described in detail. Another innovation is that Weaver adds descriptions of the gestures used in scenes two and six. Without this information, we would have little idea of his approach to expressive mime. Here is the description of scene two together with the first of the pages devoted to the gestures used by Vulcan.

Weaver’s scenario allows us to envisage his ‘Dramatick Entertainment of Dancing’ in performance. The Loves of Mars and Venus is one of very few 18th-century ballets for which we have evidence which, even without any music or surviving choreography, gives us the possibility of recreating a seminal work.

Further Reading

Richard Ralph, The Life and Works of John Weaver (London, 1985), which includes a facsimile reprint of Weaver’s The Loves of Mars and Venus published in 1717.

Judith Milhous and Robert D. Hume, The Publication of Plays in London 1660-1800 (London, 2015)