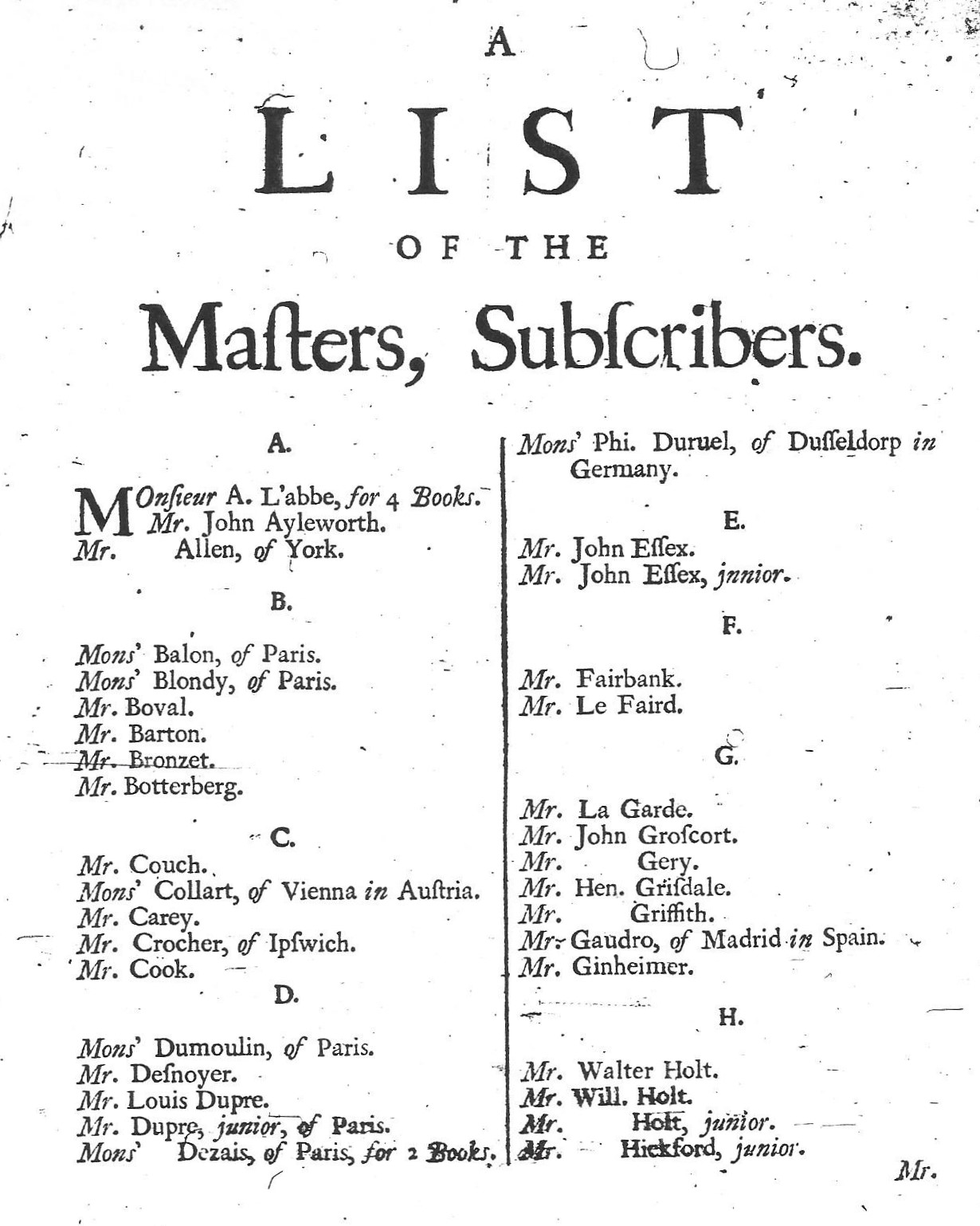

In some ways, the List of Subscribers to Kellom Tomlinson’s 1735 manual The Art of Dancing is the opposite to that for Anthony L’Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances. The publications are, of course, quite different from one another. Tomlinson’s manual of dancing is aimed at dancing masters and his, as well as their, pupils. L’Abbé’s collection of notated stage dances was surely intended for the far more specialised audience reflected by his subscribers, most of whom were professional dancers and dancing masters.

Kellom Tomlinson attracted 169 subscribers to L’Abbé’s 68, a third of whom were women (as I have pointed out, there were no female subscribers to L’Abbé’s collection). Tomlinson’s list ranges through dancing masters, nearly half of whom were (or had been) professional dancers on the London stage, as well as engravers, printers and booksellers, alongside members of the gentry and aristocracy. The gentry were predominant, accounting for around two-thirds of all the subscribers. Does this suggest the breadth of Tomlinson’s clientèle, or simply his ability to market his treatise (with or without actual teaching) to a significant number of pupils and their families? Here is the ‘List of the Subscribers Names’.

The publication history of The Art of Dancing is far from straightforward and despite a number of accounts of it (see the reading list below) still calls for fresh, detailed research. I looked at the rivalry between Tomlinson and John Essex, over the latter’s translation of Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à danser, in my post The Dancing Master’s Art Explained: Pierre Rameau, John Essex and Kellom Tomlinson. Closer reading of Tomlinson’s advertisements suggests a number of issues I did not pursue there. In the context of this post, it is worth saying again that Tomlinson had first advertised for subscribers to The Art of Dancing in 1726, but publication of his treatise was deferred until 1735. Over that period of delay, twenty of his subscribers died, including Thomas Howard, 8th Duke of Norfolk (1683-1732) and the dancing master, notator and publisher Edmund Pemberton (d. 1733). In this post, I will not go through the List of Subscribers in detail but I will look at some of the identifiable groups as well as some of the individuals within it. Tomlinson dedicated most of his engraved illustrations to individual pupils and I will also look at one or two of these.

Within the context of subscribers to works by dancing masters, one group of particular interest is that comprised of other teachers of dancing. Twenty-two men in the list have the epithet ‘Dancing-Master’. Ten of them can readily be identified as professional dancers. L’Abbé is there, as is John Essex, P. Siris and John Weaver – all of whom had themselves published treatises, as well as notated dances and collections of dances. Thomas Caverley was a subscriber, too – hardly surprising since the treatise focusses on ballroom dancing and Tomlinson had been his pupil. Among those dancing masters still appearing professionally on the stage, Leach Glover stands out as one of the leading dancers at Covent Garden who would shortly succeed Anthony L’Abbé as royal dancing master. It is interesting that the other subscribers include John Rich, described as ‘Master of the Theatres Royal in Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, and Covent-Garden’.

The female subscribers to The Art of Dancing include Mrs Booth, ‘the celebrated Dancer’. She had recently retired from the stage when the treatise was finally published, but may well have set down her name while she was still London’s leading female professional dancer. The list also has Mrs Bullock, ‘Dancer, at the Theatre in Goodman’s Fields’. Ann Bullock (née Russell) had begun her career around 1714 and by 1735 was in her final years on the stage. Like Mrs Booth, she had been among the dancers represented in L’Abbé’s choreographies in A New Collection of Dances in the mid-1720s.

Turning away from dancers and teachers of dancing, Tomlinson’s list includes five engravers. Two of them – George Bickham Junior and John Clark, are recorded as engravers who had worked on the plates added to The Art of Dancing. There were, in addition, two booksellers and a printer – Messieurs Knapton and Henry Lintot (who subscribed for three copies) were the booksellers and James Mechel was the printer. Were they involved in printing and selling Tomlinson’s manual? His title page says only ‘Printed for the Author’ and that it could be ‘had of him’ at his home address.

The feature that most clearly sets Tomlinson’s List of Subscribers apart from its predecessors is the number of individuals who may reasonably be assumed to have engaged him as a dancing master to teach them or their children. They make up around 80% of the whole list and many of them are identified with particular places, mostly in England. Tomlinson may well have taught the aristocracy in their London houses, but other evidence suggests that he travelled to their country seats and taught in the surrounding areas too.

Among his subscribers is ‘The Lady Curzon of Kedleston in Derbyshire’ and plate six in book one is dedicated to ‘my ever respected Scholars Nathaniel Curzon and Assheton Curzon Esqrs. Sons to Sir Nathaniel Curzon of Kedleston’.

Lady Curzon was Mary (née Assheton), wife of Sir Nathaniel 4th Baronet Curzon and the mother of the two boys. This portrait of her with them, by Andrea Soldi and painted around 1738 to 1740 a few years after the publication of The Art of Dancing, hangs at Kedleston.

Tomlinson’s plate was not intended to portray the two boys themselves, who in 1735 were only nine and six years old. As he declared in his Preface to The Art of Dancing:

‘The Figures in each Plate are designed only to show the Postures proper in Dancing, but not to bear the least Resemblance to any Person to whom the Plate is inscribed.’

Did Tomlinson use dancers as models for these images (which he ‘invented’ himself) and, if so, who might they have been?

A chance discovery, made a few years ago in the course of another line of research, provides additional evidence of Tomlinson’s assiduous use of advertising to further his career as a dancing master. An advertisement in the Derby Mercury for 12 December 1734, shows that he had been teaching ‘in and about’ Derby (and so in the vicinity of Kedleston).

He must also have been teaching the young Nathaniel and Assheton Curzon at Kedleston in the summer of 1734. Was that when he secured a subscription from Lady Curzon of Kedleston, or had his teaching and her patronage begun earlier in London? It is surely significant that another ten of the subscribers to The Art of Dancing describe themselves as being ‘in and about’ Derby. Tomlinson evidently established an ongoing professional relationship with the area, for he was still advertising in the Derby Mercury as late as 1756 (Tomlinson died in 1761). This advertisement is dated 11 June 1756:

Kellom Tomlinson has been the subject of research, as the reading list below shows, but I can’t help thinking that there is far more work that can be done on him, The Art of Dancing and his various circles of patrons and pupils.

Reading list:

Carol G. Marsh, ‘French Court Dance in England, 1706-1740: A Study of the Sources’ (unpublished PhD thesis, City University of New York, 1985), see pp. 11-121, 150-155.

A Work Book by Kellom Tomlinson, ed. Jennifer Shennan (Stuyvesant, NY, 1992)

Jennifer Thorp, ‘“Borrowed Grandeur and Affected Grace”: Perceptions of the Dancing-Master in Early Eighteenth-Century England’, Music in Art, XXXVI, no. 1-2 (Spring-Fall 2011), 9-27 (see pp. 18, 20-21)

Jennifer Thorp, ‘Picturing a Gentleman Dancing Master: A Lost Portrait of Kellom Tomlinson’, Dance Research, 30.1 (Summer 2012), 70-79 (see pp. 74-76)