The Cotillon

A few years ago, I wrote a series of posts about the cotillon steps recorded by London’s dancing masters in the 1760s. In 1762, De la Cuisse (who began the cotillon craze by publishing these dances) listed six steps in his Le Repertoire des bals ou theorie-pratique des contredanses – balancé, rigaudon, contretems, chassé, pirouette and pas de gavotte (the demi-contretems, which he described as ‘un Pas naturel; C’es le Pas fondamental de la Contredanse’). All are familiar from the dance manuals of the early 1700s. Between them, Gallini, Gherardi and Villeneuve added another six – assemblé, glissade, ‘brizè à trois pas’, ‘chassé à trois pas’, double chassé and sissonne. Three of these were also described in the earlier manuals, while three – the brizé and chassé ‘a trois pas’ and the double chassé were apparently more recent.

The Quadrille

The step vocabulary for the early 19th-century quadrille was more extensive and some of the steps were certainly more challenging than any used in the cotillon. One of the earliest works to deal with the quadrille was Notions élémentaires sur l’art de la danse by J. H. Gourdoux-Daux, published in Paris in 1804. The second edition was titled Principes et notions élémentaires sur l’art de la danse pour la ville and appeared in 1811. It was presumably this edition that was translated into English for publication in Philadelphia in 1817 as Elements and Principles of the Art of Dancing as used in Polite and Fashionable Circles. This translation describes nine steps for use in quadrilles – the ‘change of foot’ (changement de jambe), assemblé, jeté, sissonne, échappé, temps levé, grand coupé, chassé and glissade. Only one, chassé, is among the cotillon steps prescribed by De la Cuisse, while three more appear in the collections published in London – assemblé, glissade and sissonne. The last of these occurs only in Villeneuve’s Collection of Cotillons and he does not describe it. By the time Gourdoux-Daux was writing, the sissonne had become a spring from two feet to one, beginning in third position and ending with the free foot either extended to second or fourth position or brought into the ankle. It is recognisable as the second part of the pas de sissonne recorded in the early 1700s.

Gourdoux-Daux published a third edition of his treatise titled simply De l’art de la danse in 1823, which is accessible digitally. It adds a tems du balonné, pas de bourrée, tems de cuisse, demi-contretems, brisé and entrechat. His third edition is described as ‘revue, corrigé et augmenté’, indicating that it contains new material. However, without access to Gourdoux-Daux’s earlier editions, it is not possible to know whether he included any of these steps before 1823 or whether his American translator simply omitted them as either not generally used or, perhaps, not appropriate for social dancing.

In 1822, Alexander Strathy published his Elements of the Art of Dancing in Edinburgh. His list has twelve quadrille steps – assemblé, jeté, glissade, sissonne, temps levé, chassé, échappé, pirouette, changement de jambe, pas de Zéphyre or pas battu, jeté tendu and jeté du côté. His vocabulary overlaps with that of Gourdoux-Daux, but both have steps not included by the other.

The only other treatise I will look at here is Charles Mason’s A Short Essay on the French Danse de Société published in London in 1827. His vocabulary overlaps with both Gourdoux-Daux and Strathy and also includes steps they do not list. Mason’s list has twenty of what he calls ‘Les Mouvemens’ – changement de jambes, assemblé, jeté, sissonne, tems levé, chassé, glissade, jeté ballonné, tems de Zéphyre, coupé, pas de basque, pas de bourrée, tems de ‘coudepied’, jeté brisé, pas tombé, fouetté, contretems, pirouette, emboîté and petits battemens. Some of these may have been embellishments to steps, rather than steps in their own right, and some may have been used only within the ‘Differens Enchainemens de Pas’ Mason refers to on his title page.

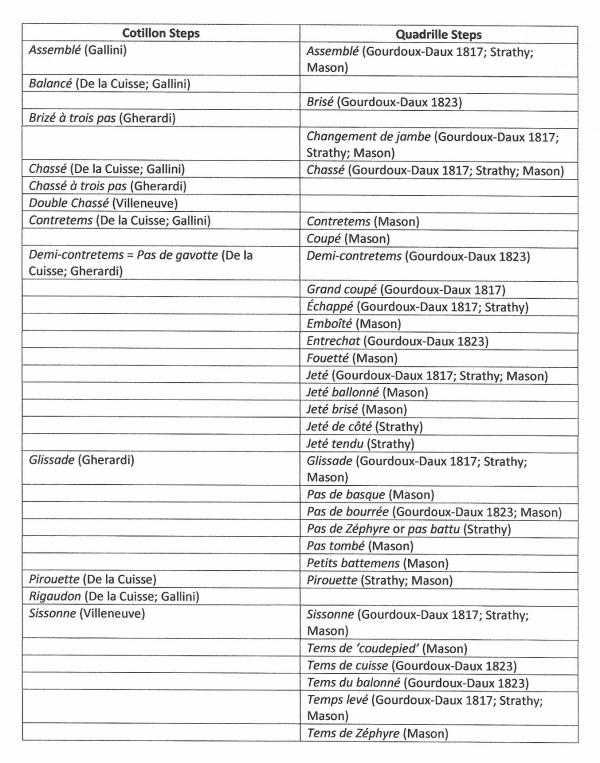

In the following table I have tried to set out the steps recommended for the cotillon and quadrille respectively, with the name of each dancing master to include it listed in order of the date of their first publication in which it appears. For the purposes of this investigation, I have omitted the Allemande step used in so many cotillons – it is probably worth another post of its own (although I did write about it a few years ago). There were, of course, several other works on dancing – and the quadrille – published in the early decades of the 19th century, so my list of steps is probably far from complete and it is certainly not definitive. How and why did the step vocabulary change and expand so much as the cotillon gave way to the quadrille?