In 1725, Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à danser was published in Paris. Just three years later, a translation by John Essex entitled The Dancing-Master; or, the Art of Dancing Explained appeared in London. It was heralded by an advertisement in Mist’s Weekly Journal for 13 January 1728, which stated that the treatise would be published ‘Next Week’ and promised that it would be ‘illustrated with 60 Figures drawn from the Life’ (Rameau’s title page had promised that his treatise was ‘Enrichi de Figures en Taille-douce’ without saying how many). The price was to be one guinea (equivalent to around £120 today).

Just over a year earlier, the issues of the Evening Post for 13-15 and 20-22 October 1726 had carried advertisements soliciting subscriptions for another English dance manual, Kellom Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing. Tomlinson promised ‘many Copper Plates’ for the illustration of his treatise indicating how important such images were. There was another advertisement in the London Journal for 3 December 1726, in which Tomlinson promised that The Art of Dancing was ‘now partly finished’ and would be published once he had sufficient subscribers to cover his costs. As we know, Tomlinson’s work would not appear until 1735 but his 1726 advertisements may have acted as a spur to Essex to produce his translation of Rameau’s treatise.

If John Essex had intended to compete with Kellom Tomlinson, it seems that he succeeded. In his Preface to The Art of Dancing, Tomlinson gave his reaction to reading about the imminent publication of The Dancing-Master in Mist’s Weekly Journal:

‘This gave me no small Surprize, having never before heard of either any such Book, or Author. Had it been my Fortune to have known, either before, or after I undertook to write on this Art, that such a Book was extant, my Curiosity would certainly have led me to have consulted it; and had I approved it, ‘tis highly probable, I should have given the World a translation of it, with some additional Observations of my own.’

Tomlinson’s claim to be ignorant of the existence of Rameau’s Le Maître à danser needs some investigation, given the tight-knit community of London’s leading dancing masters and the importance of French treatises and notated dances to their work (evidenced in Tomlinson’s surviving notebook). His immediate response was to defend his own treatise, which he did with an advertisement in Mist’s Weekly Journal for 27 January 1728.

Thereafter, Kellom Tomlinson remained quiet until he was able to return to advertising the forthcoming publication of The Art of Dancing, beginning in the London Evening Post for 20-22 December 1733. He may have spent the intervening period enhancing his treatise with additional plates to accompany his text, so that he could challenge Essex directly.

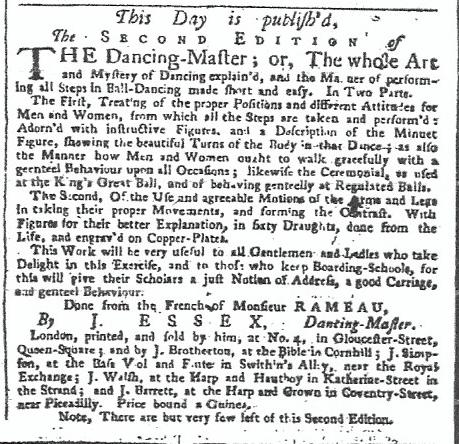

In the meantime, successive advertisements suggest that Essex’s The Dancing-Master may not have sold well. There were notices in the Country Journal or the Craftsman for 22 November and 27 December 1729, both saying ‘This Day is Published’ although The Dancing-Master had first appeared nearly two years earlier. Then, the Grub Street Journal for 23 December 1730 announced the publication of the ‘Second Edition’ of the treatise (which is dated 1731 on its title page). However, this was not a new edition at all but a reissue of unsold copies of the first edition, with a fresh title page and an additional leaf with approbations from Pecour (who was recommending Rameau’s original treatise) and Anthony L’Abbé. This edition was advertised successively in the Country Journal or the Craftsman on 1 January and 5 May 1733.

The changes to the title page wording (with an extended sub-title and a recommendation to likely purchasers) were doubtless for marketing purposes.

Later that year, the Grub Street Journal for 8 November 1733 advertised a ‘Second Edition with Additions’. This notice reproduces the wording of Essex’s title page, but it is worth paying close attention to the final paragraph.

Essex’s concern about the quality of his plates may have been prompted by his discovery that Kellom Tomlinson was finally ready to publish The Art of Dancing with its ‘many Copper Plates’ as announced in the London Evening Post for 20-22 December 1733.

I will have to leave a discussion of the plates in both The Dancing-Master and The Art of Dancing for another post.

Essex followed up his November 1733 advertisement with another in the Country Journal or the Craftsman on 5 January 1734, saying ‘This Day is Published’ but otherwise word-for-word as in the Grub Street Journal. Tomlinson’s next notice, in the London Evening Post for 18-20 April 1734, advised his subscribers that publication would be deferred to the following January ‘by Reason of the Advance of the Season, and the Emptiness of the Town’. He was hinting that many, if not most, of those who had subscribed to his treatise were the ‘Quality’ who left London for their country estates over the summer and early autumn. Essex seems to have fallen silent, at least I have not discovered further advertisements by him in the mid-1730s. The next notice was Tomlinson’s, in the London Evening Post for 8-10 May 1735, announcing the publication of The Art of Dancing on 26 June.

The additional delay was to allow the Engraving Copyright Act to become law. It had been championed by William Hogarth among others to protect the rights of artists whose original works were the subject of engravings. Tomlinson had himself drawn the images which were engraved by several leading printmakers for his treatise. The Art of Dancing cost two guineas to subscribers and two and a half guineas to others (equivalent to £250 and nearly £300 today).

Kellom Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing might have been more original and more handsomely produced than The Dancing-Master, as well as being supported by the nobility and gentry, but it did not sell well either. An advertisement in the London Daily Post for 11 December 1736 includes it among ‘Books sold cheap’ by William Warner. According to a notice in the London Evening Post for 5-7 November 1741, Tomlinson was himself selling copies for £1.11s.6d – rather less than the two and a half guineas he was originally charging – although an advertisement in the Country Journal or the Craftsman for 2 January 1742 quotes his original price. In the same newspaper for 31 December 1743, Tomlinson told intending purchasers that ‘there now remain but a small Number unsold of the Work’. The London Evening Post for 9-11 October 1746 advertised a ‘Second Edition’ as published that day, although surviving copies are dated 1744. The pagination of the two editions suggests that the second was in fact a reissue. Here are their respective title pages.

The last advertisement for the ‘Second Edition’ of Essex’s The Dancing-Master appeared in the Daily Advertiser for 12 January 1744 and there are surviving copies with this date on their title pages. John Essex was buried at St Dionis Backchurch in London on 6 February 1744.

I have come across two later advertisements for Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing. One is in the London Evening Post 30 January – 1 February 1752, offering the ‘Second Edition’ which is ‘colour’d, in a most beautiful Manner, and bound’ for five guineas (equivalent to more than £600 today). The other, in the Whitehall Evening Post or London Intelligencer for 9 November 1758, has Tomlinson offering ‘The Original Art of Dancing’ for three guineas. The Whitehall Evening Post or London Intelligencer for 18-20 June 1761 reported ‘Tuesday died, of a Paralytick Disorder, in Theobald’s Court, East Street, Red-Lion-Square, Mr. Kenelm Tomlinson, Dancing-Master, in the 74th Year of his Age’.

The publication history of these two early 18th-century dance manuals illuminates the commercial and social as well as the artistic context within which London’s dancing masters worked. They were intended for a monied if not an elite clientele. Both The Dancing-Master and The Art of Dancing are worth detailed research which goes well beyond a concern with the steps, style and technique that are their subject matter.

References

Both of these treatises were studied in detail by the American dance historian Carol G. Marsh in her PhD thesis ‘French Court Dance in England, 1706-1740: a Study of the Sources’ (City University of New York, 1985). In this post, I have drawn on and tried to add to her work.

![John Essex, For the Further Improvement of Dancing [1715?], plates 1 - 4](https://danceinhistory.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/essex-1715.jpg?w=211)

![John Essex, The Princess's Passpied, [1715?], first plate](https://danceinhistory.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/princess-passpied1.jpg?w=201)