The notation for Anthony L’Abbé’s ballroom dance The Prince of Wales’s Saraband is one of the exhibits in Crown to Couture at Kensington Palace (the exhibition closes on 29 October 2023). It is shown out of context and with next to no explanation of its meaning so, although I have written about the dance elsewhere, I thought it would be worth a post in Dance in History to provide some information about this beguiling duet.

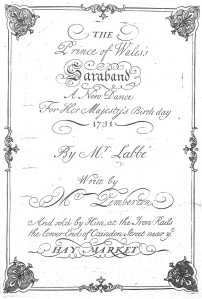

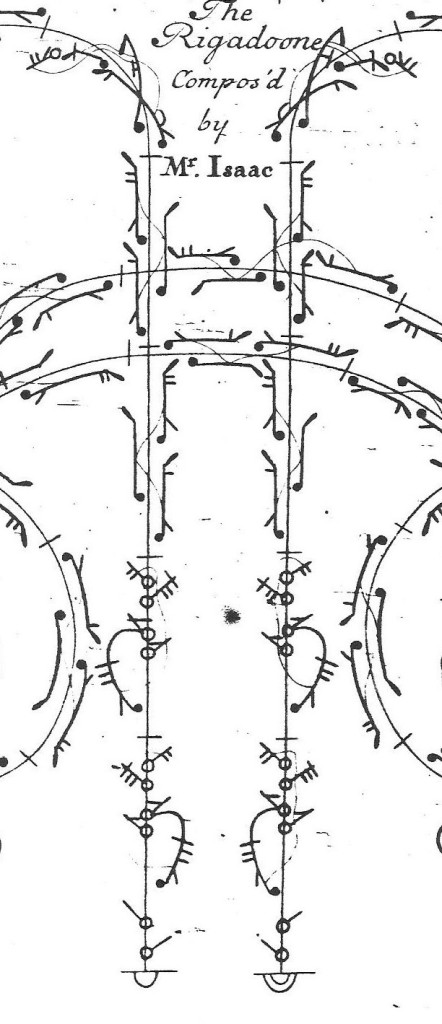

The Prince of Wales’s Saraband was one of a series of dances created by Anthony L’Abbé and published in Beauchamp-Feuillet notation by Edmund Pemberton following L’Abbé’s appointment by George I as royal dancing master around 1715. The title page makes clear that this was one of the dances choreographed by L’Abbé to celebrate the birthday of Queen Caroline, wife of King George II and mother of the Prince.

Her birthday was on 1 March and it had been celebrated at court since at least 1717, when L’Abbé’s ballroom dance The Royal George was created and published for that purpose. In that case, the title page of the dance makes no reference to the then Princess of Wales but the advertisements for the notation make it clear that the dance was in her honour.

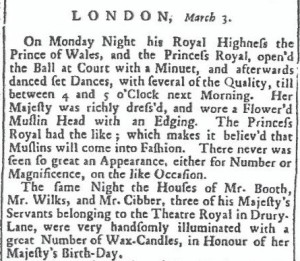

By 1731, Caroline had been Queen for fewer than four years and L’Abbé had not published a dance since the Queen Caroline which honoured her birthday in 1728. In 1731, there was a birth night ball for the Queen and the report in the Daily Advertiser for 3 March 1731 gives us some details.

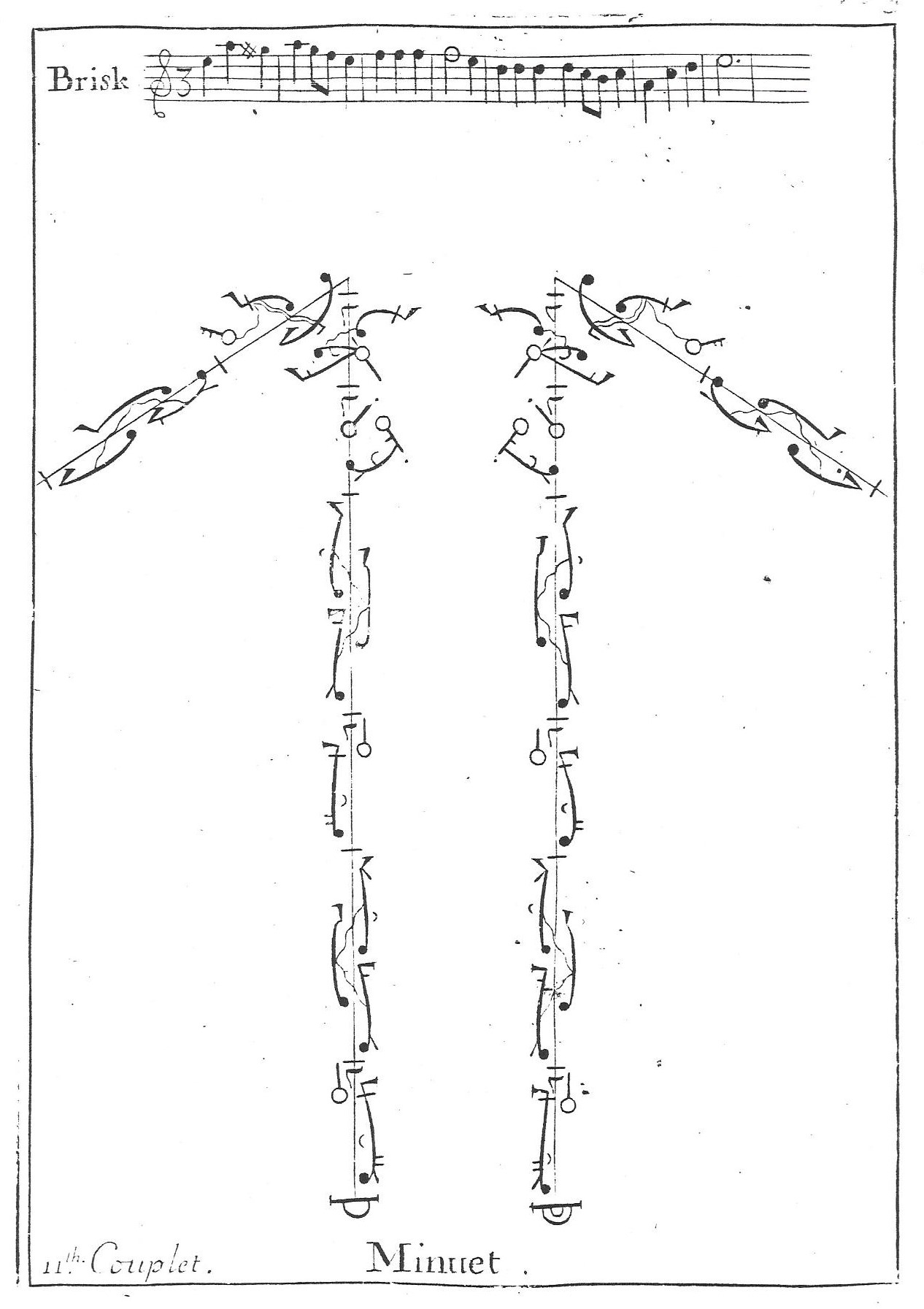

There is no mention of L’Abbé’s dance, although Frederick Prince of Wales ‘open’d the Ball’ by dancing a minuet with his sister Anne the Princess Royal. The reference to the illumination of the houses of all three of the actor-managers of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, is interesting, for The Prince of Wales’s Saraband was performed in the entr’actes at that theatre on 22 March 1731 by William Essex and Hester Booth. That first public performance was obviously also intended to honour the Queen.

The dance seems to have been admired, for it was revived at the Haymarket Theatre on 21 August 1734 and again at Drury Lane on 17 May 1735, each time performed by Davenport and Miss Brett. It was revived again at Covent Garden on 25 April and 13 May 1737, by Dupré (probably the dancer James Dupré) and Miss Norman.

Prince Frederick had remained in Hanover following the accession of his grandfather as George I in 1714. He came to England only in 1728, eighteen months after the accession of his parents to the British throne. By this time, the prince was twenty-one and he joined a family which included four sisters and a brother whom he scarcely knew. This portrait by Philippe Mercier shows Prince Frederick in the mid-1730s.

Prince Frederick’s relationship with his parents, particularly his mother Queen Caroline, became steadily more difficult after his arrival in England. In 1731, the year The Prince of Wales’s Saraband was created, this problem lay in the future.

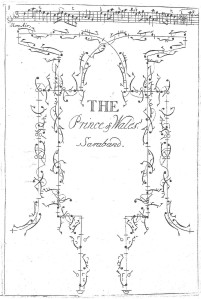

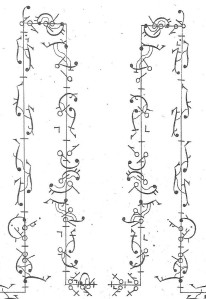

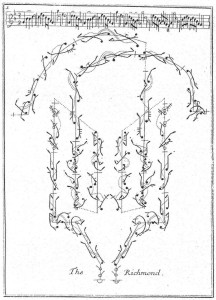

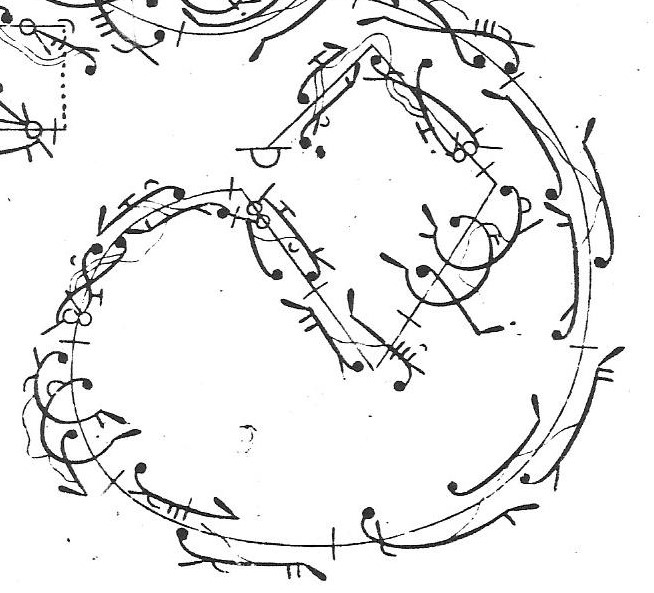

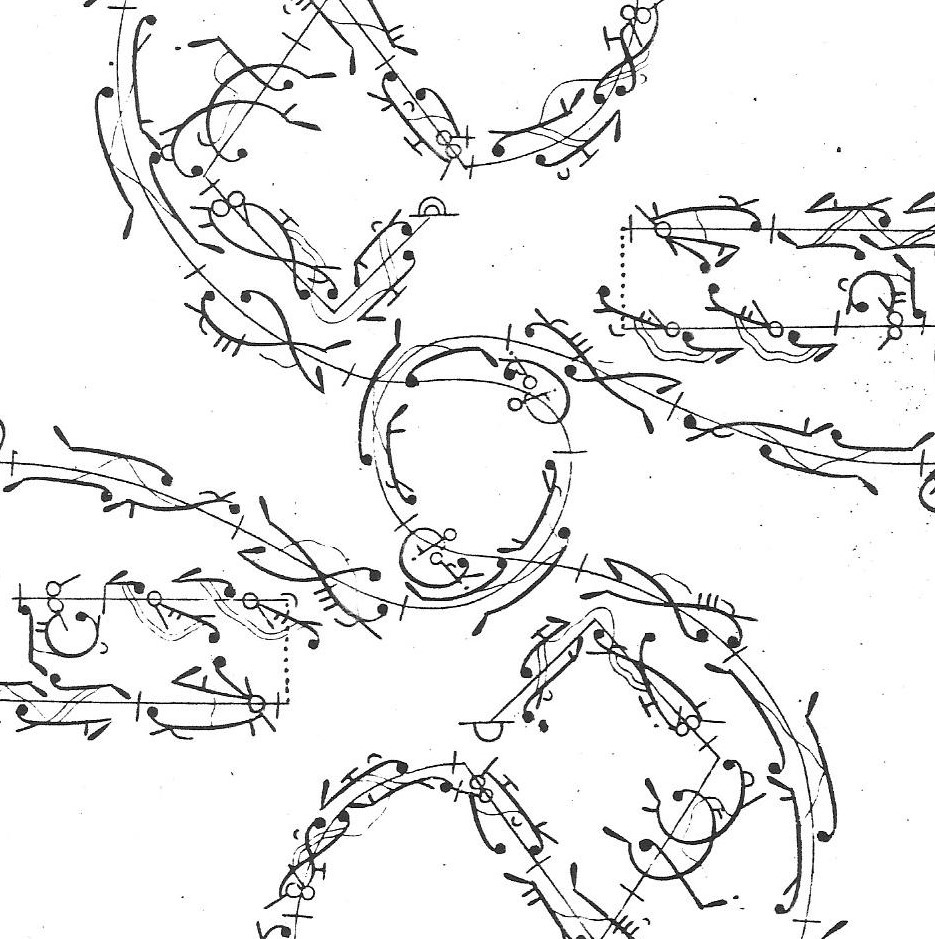

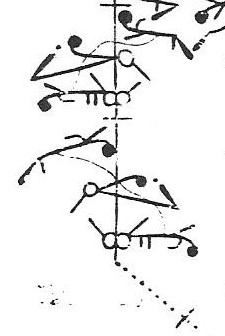

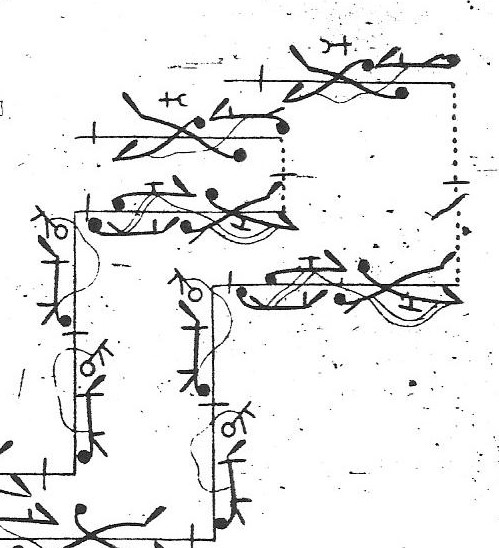

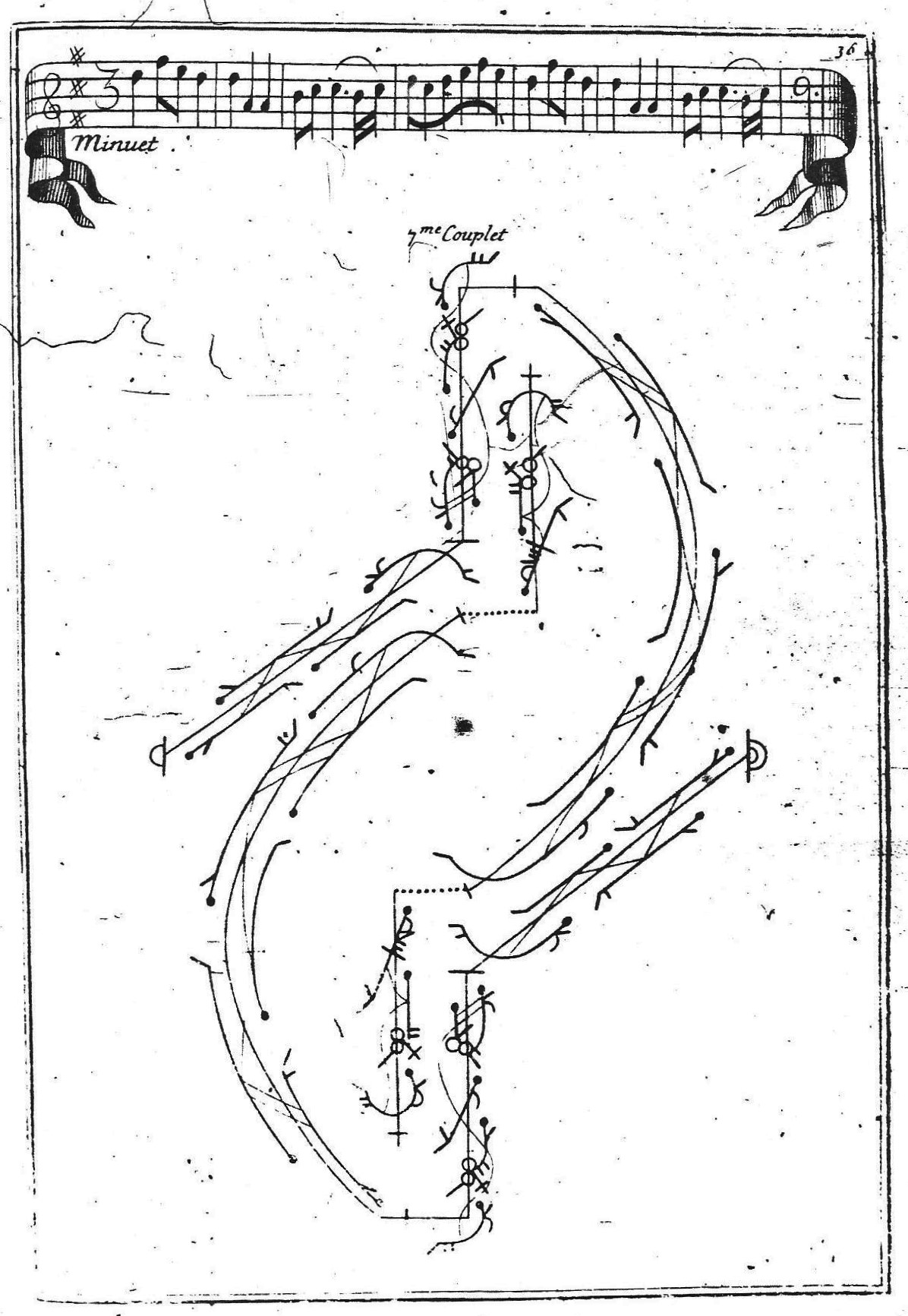

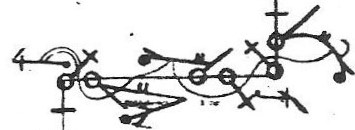

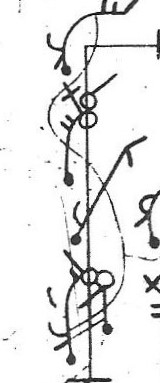

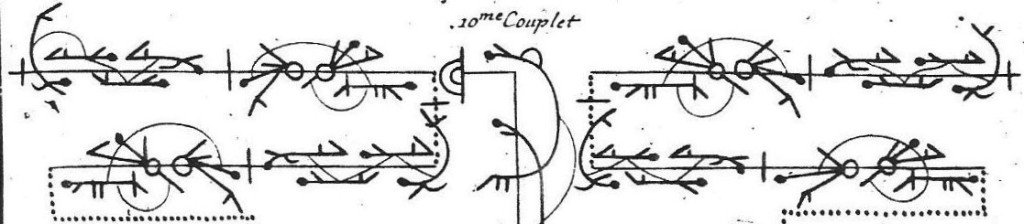

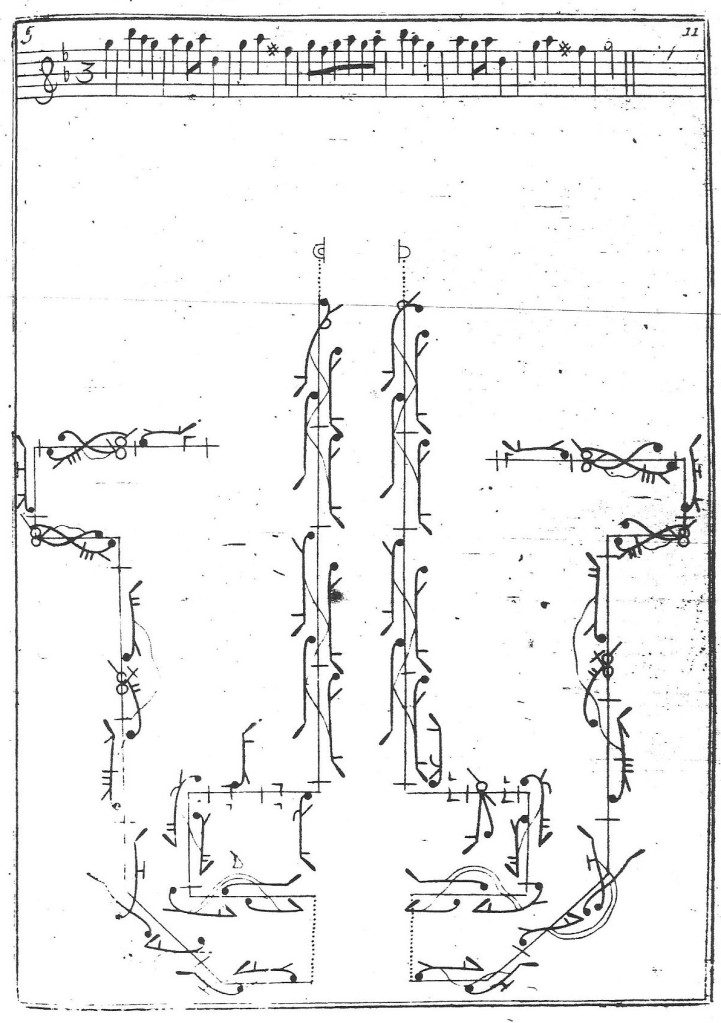

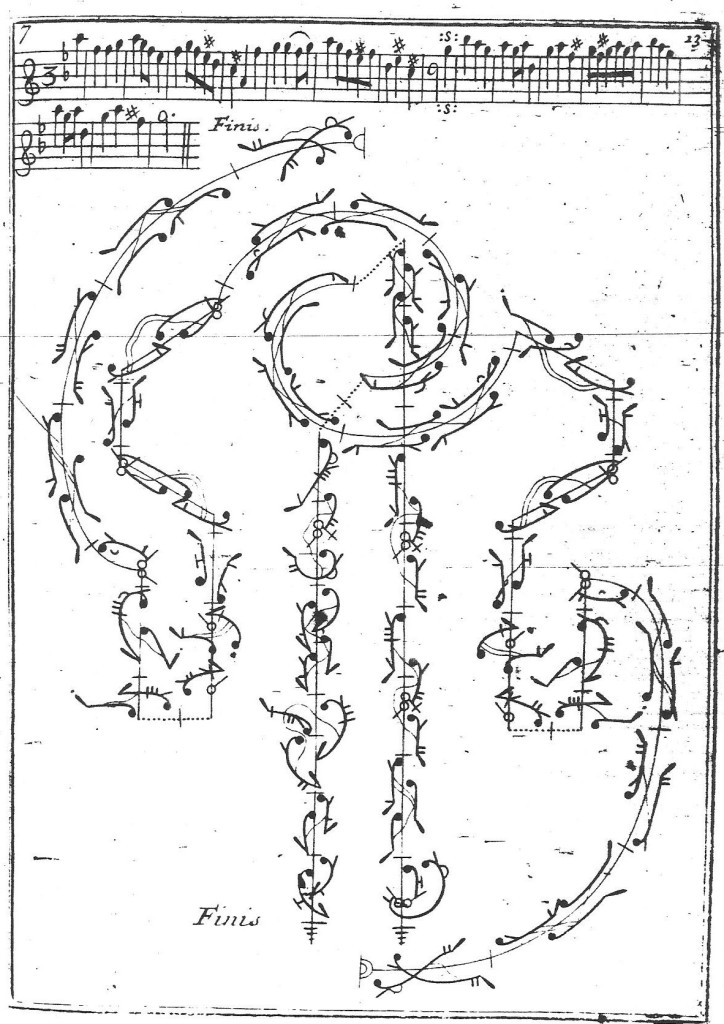

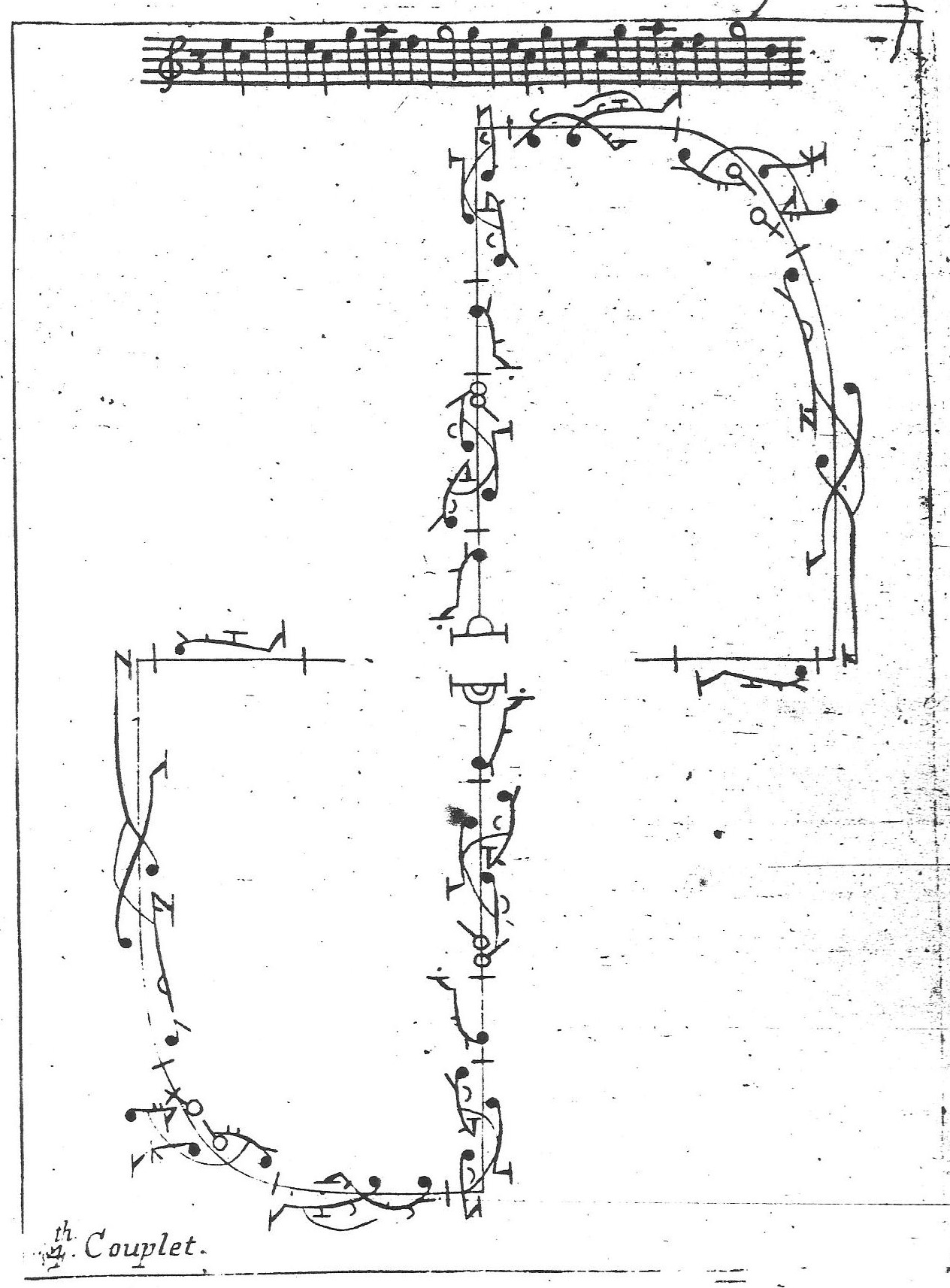

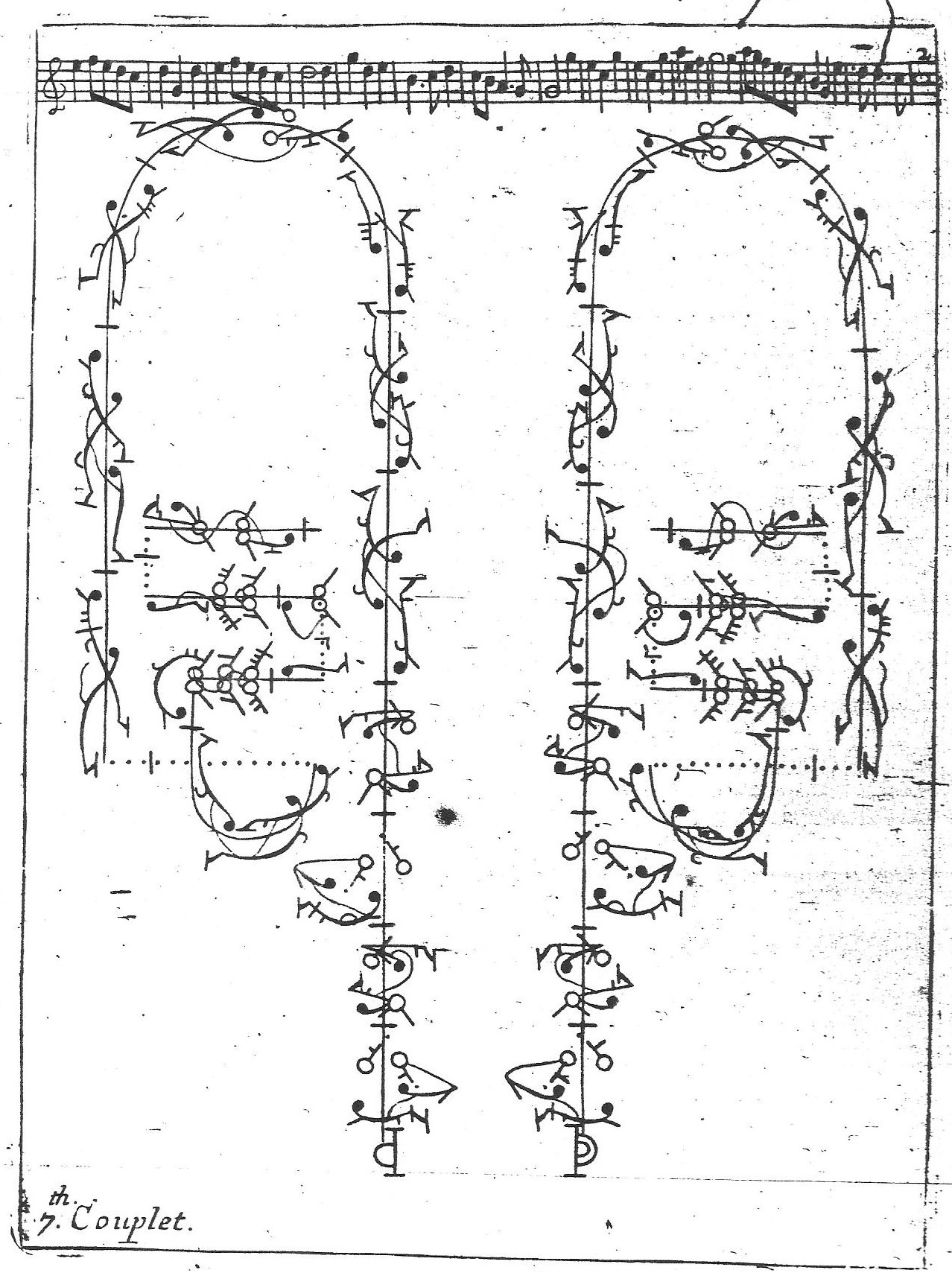

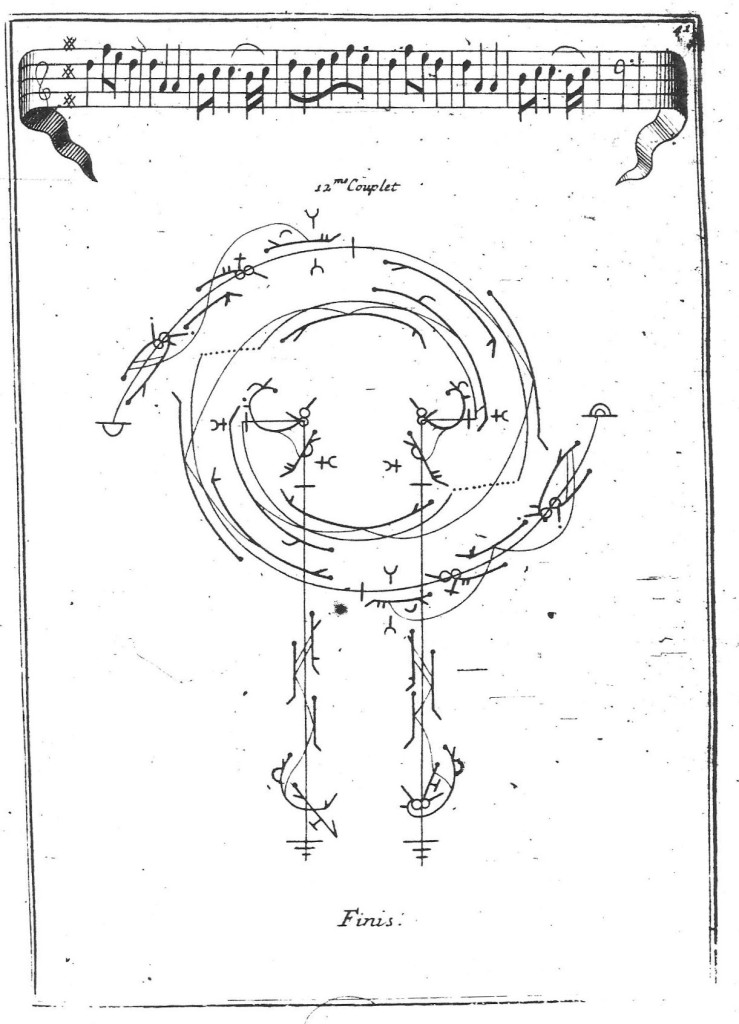

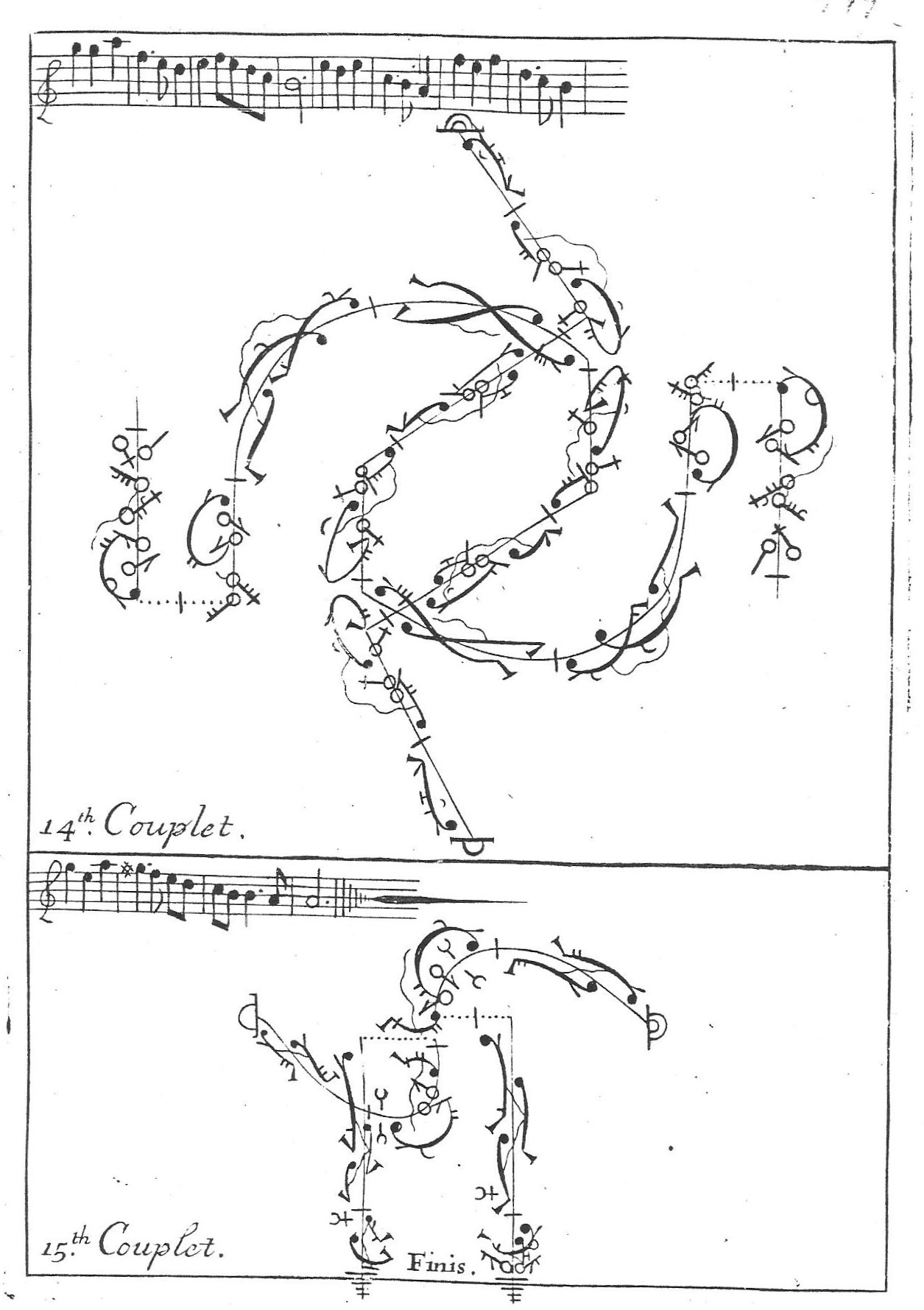

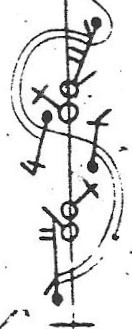

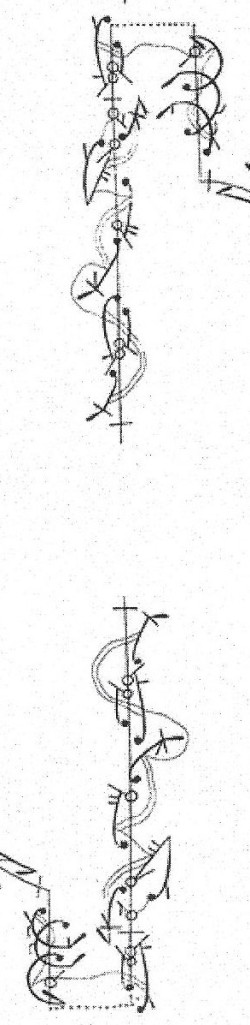

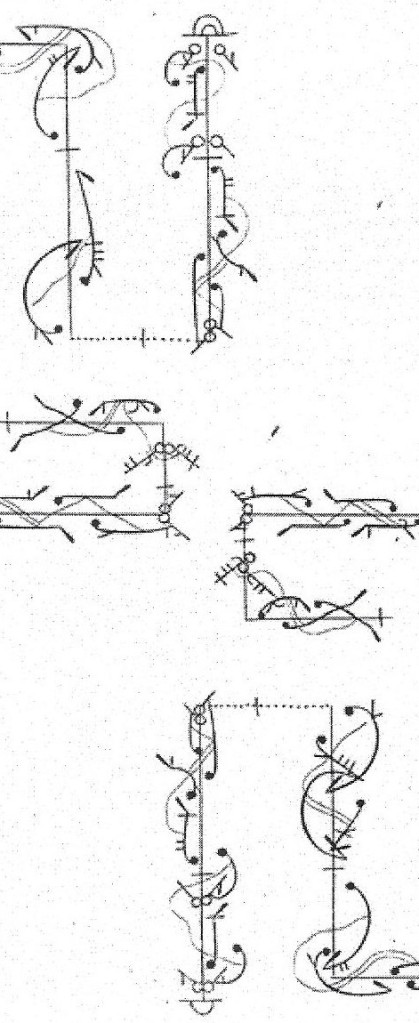

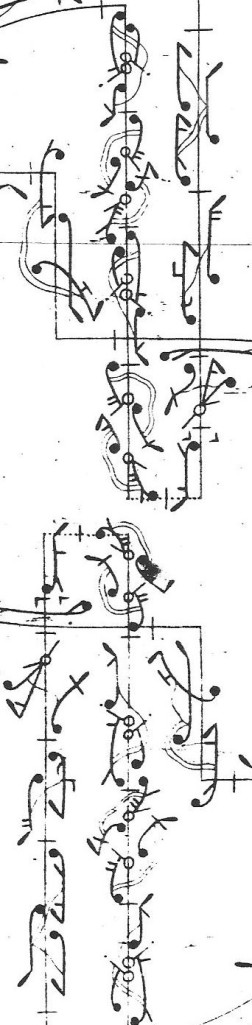

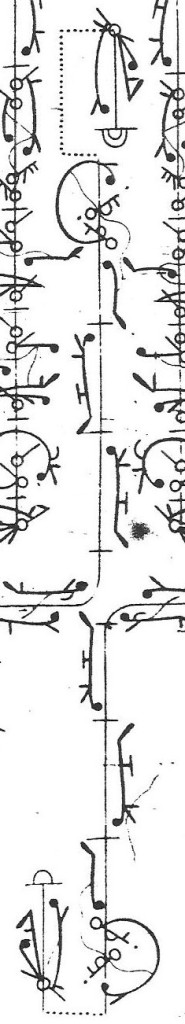

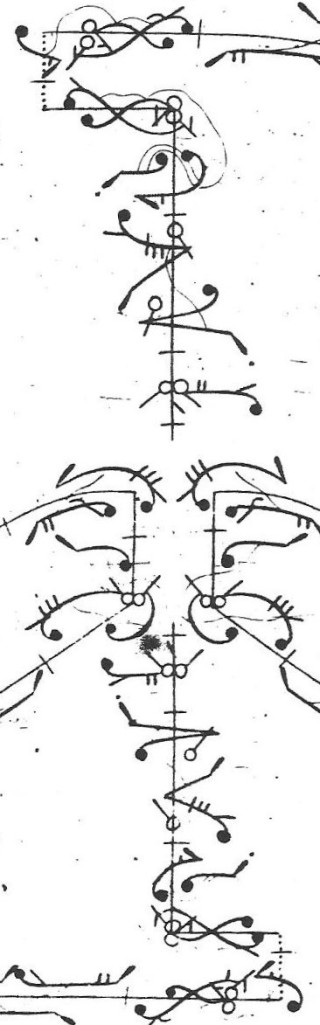

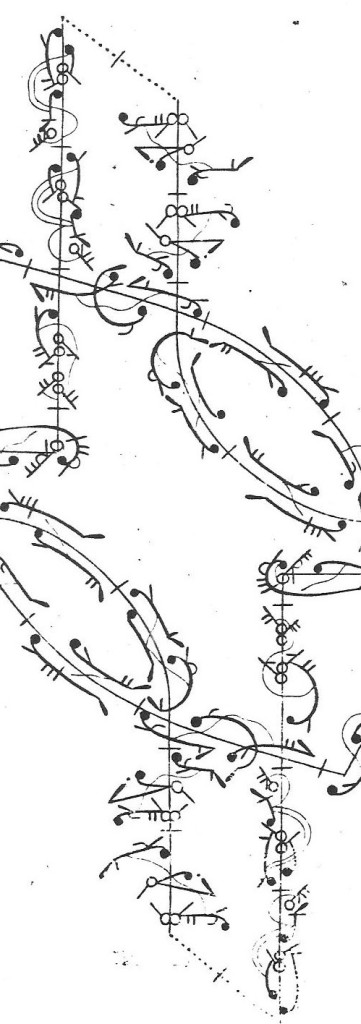

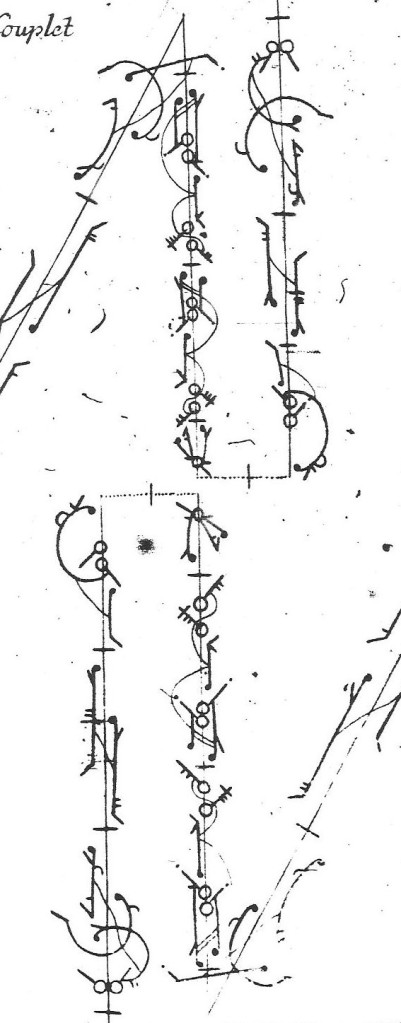

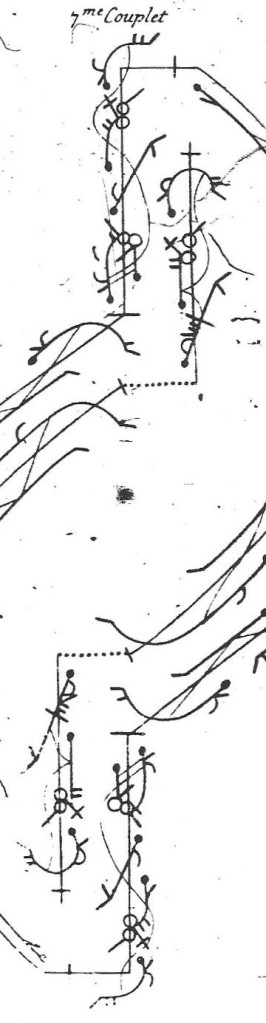

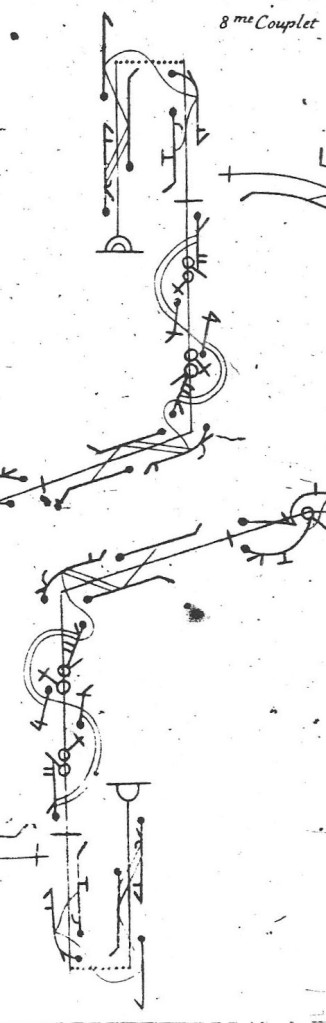

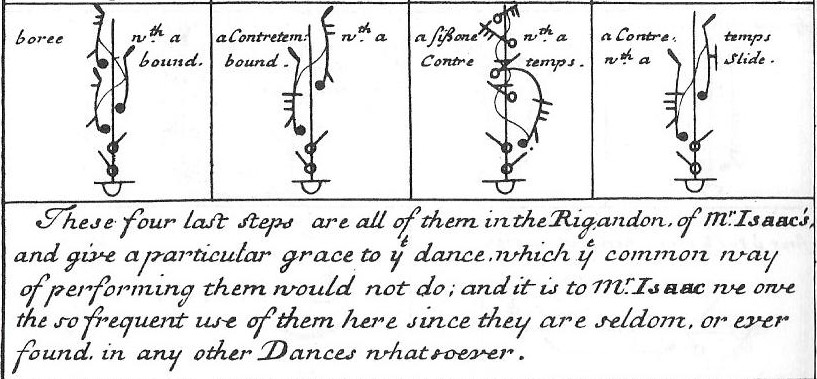

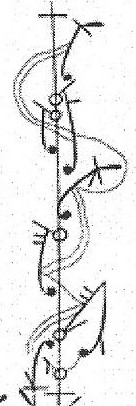

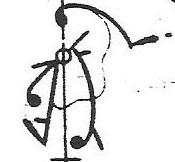

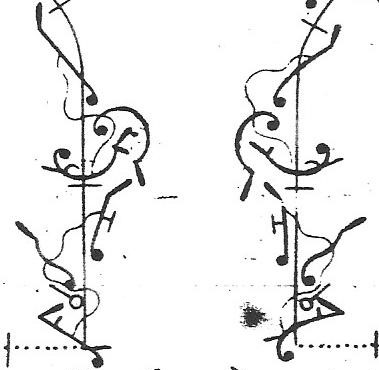

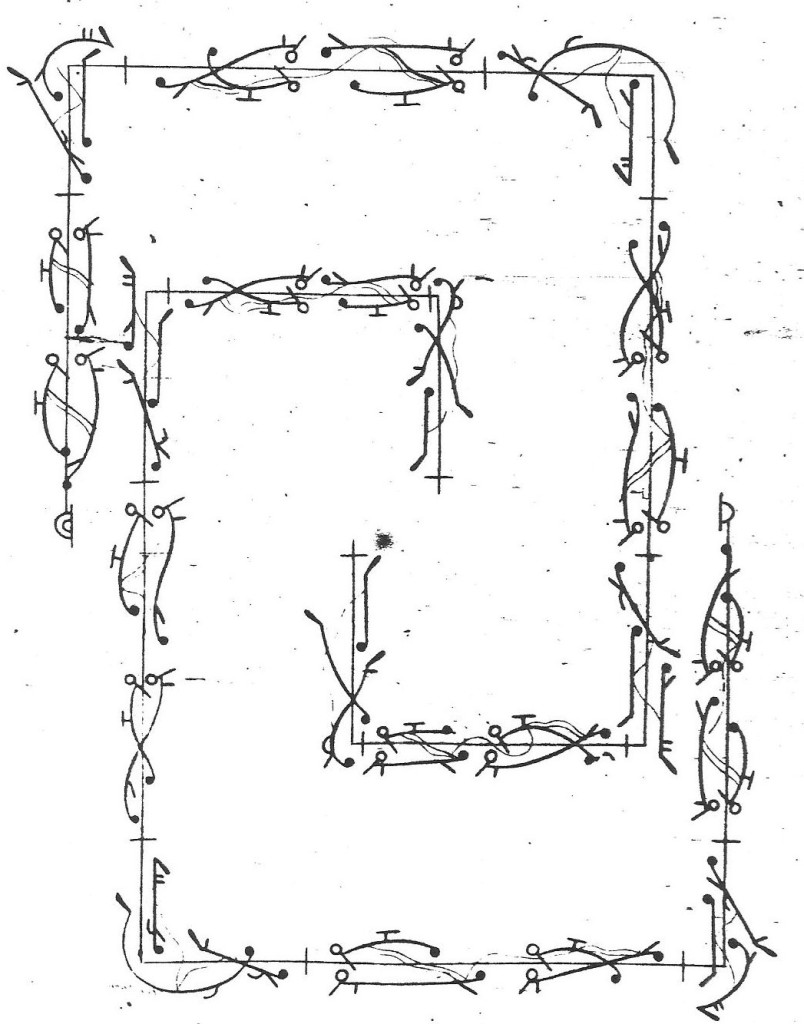

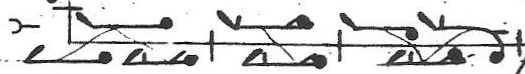

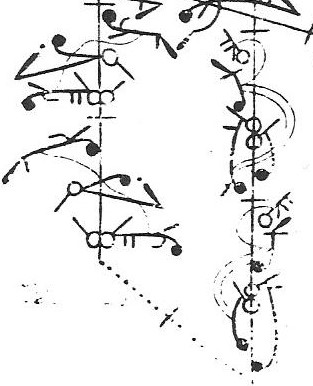

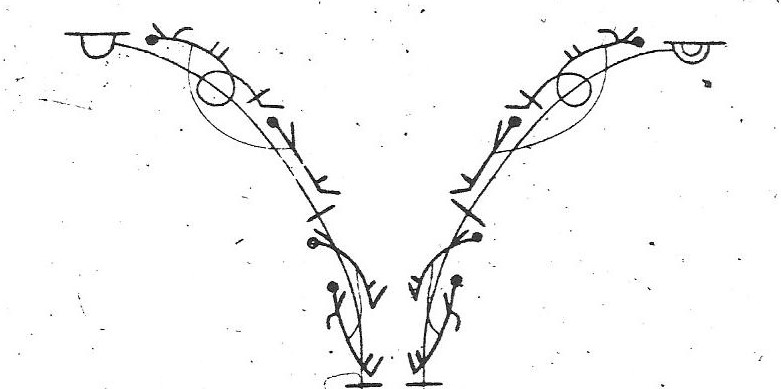

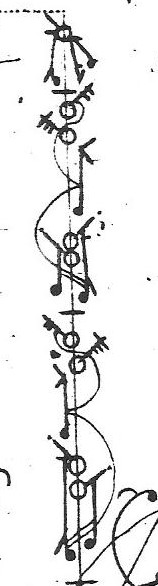

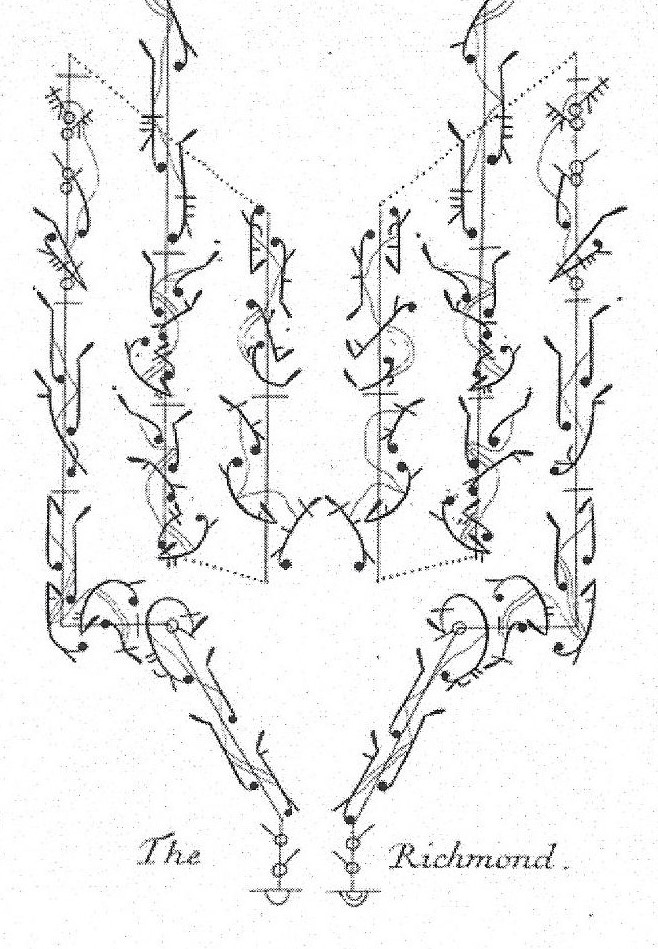

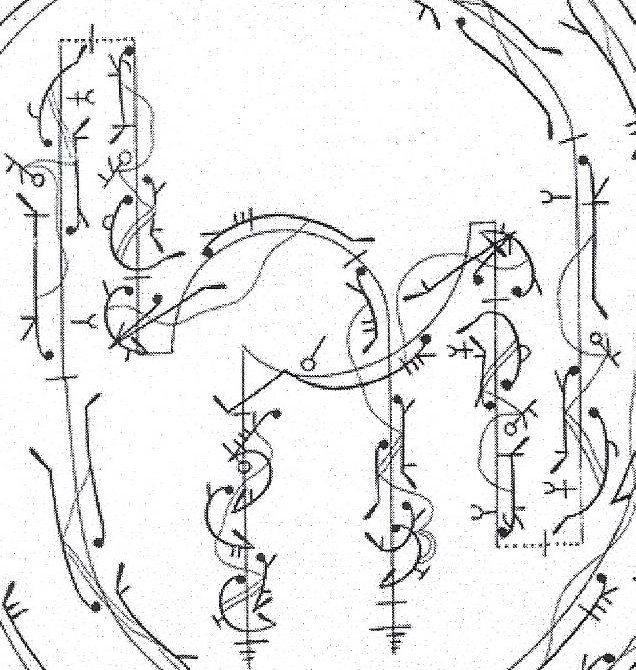

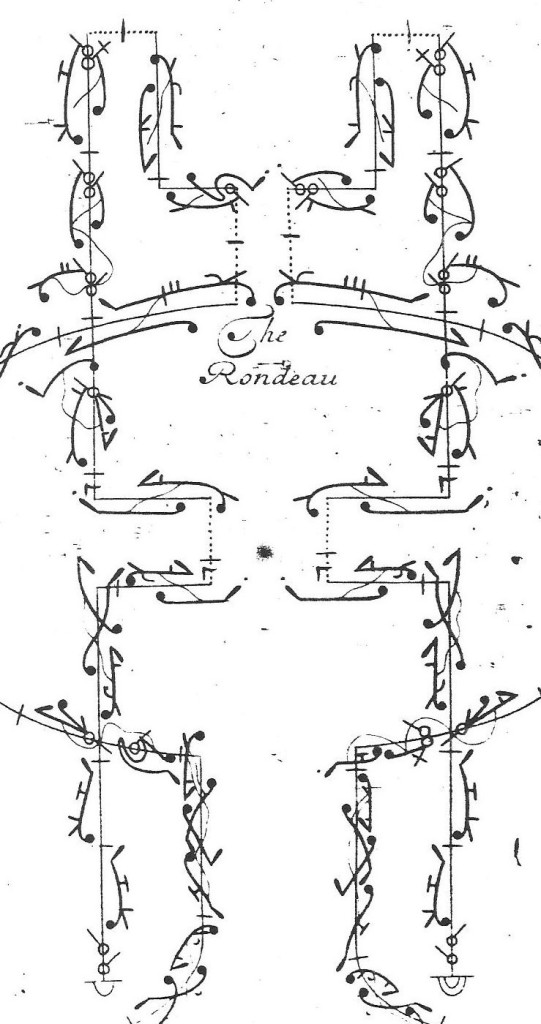

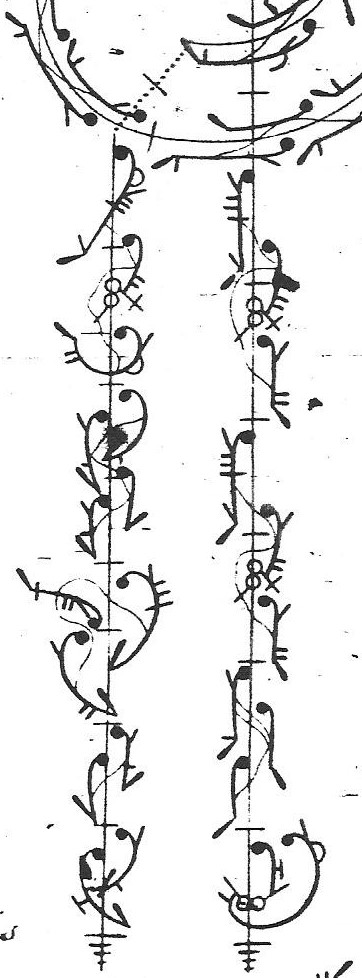

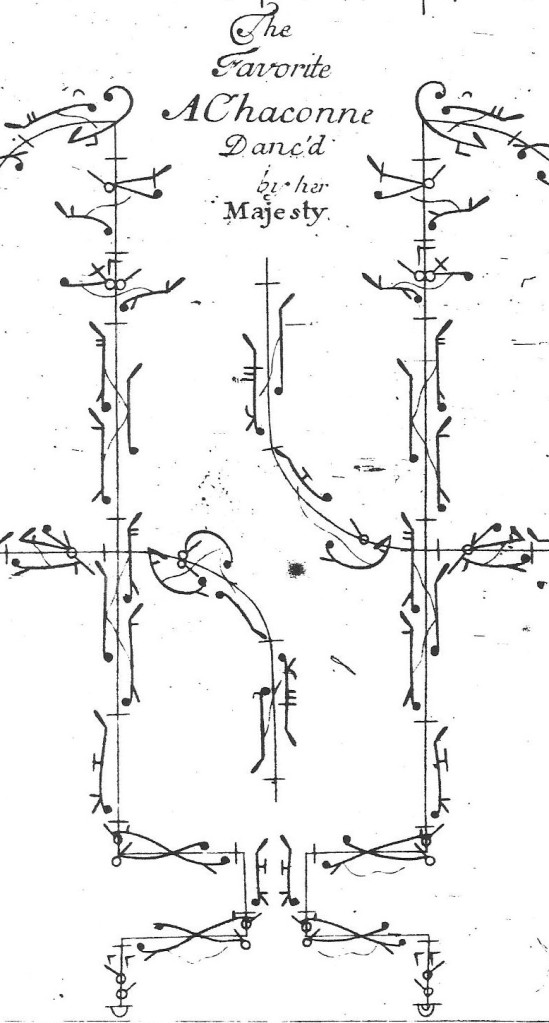

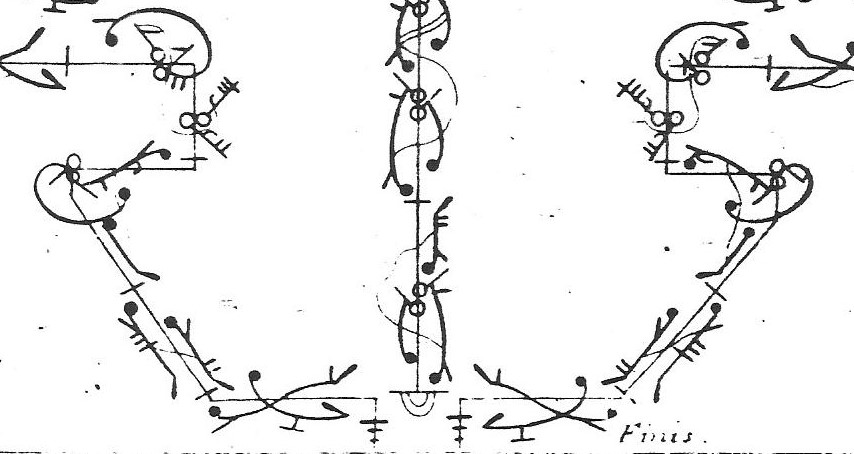

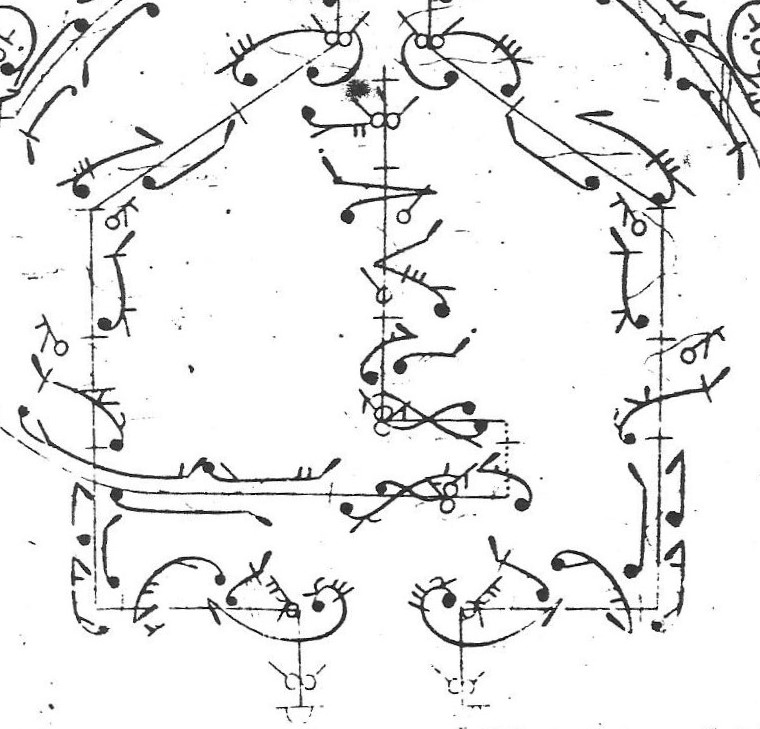

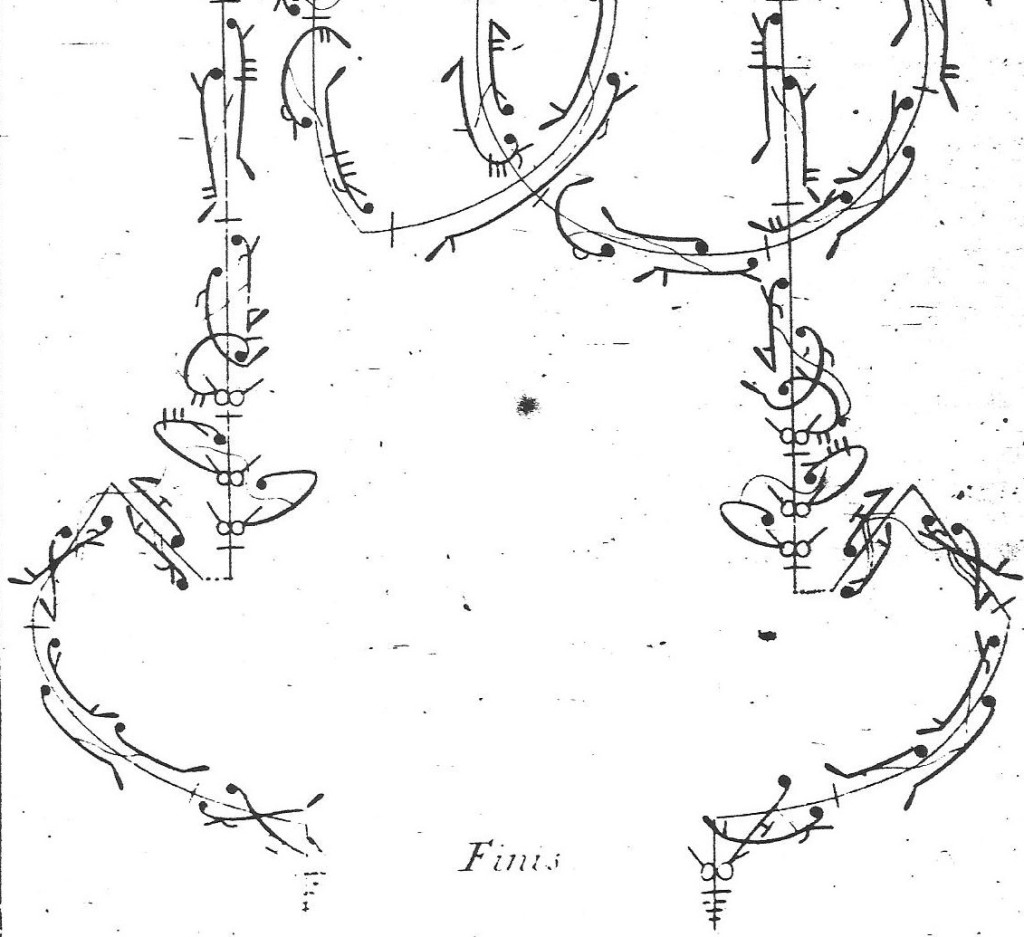

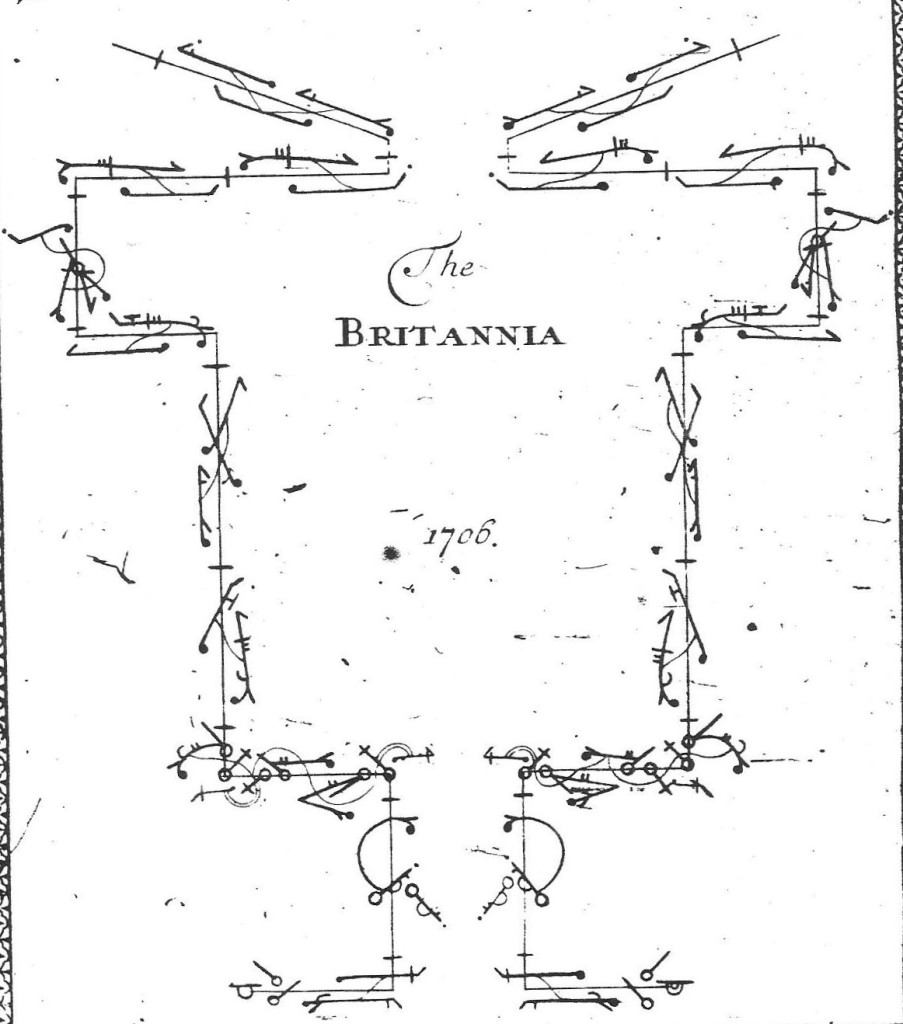

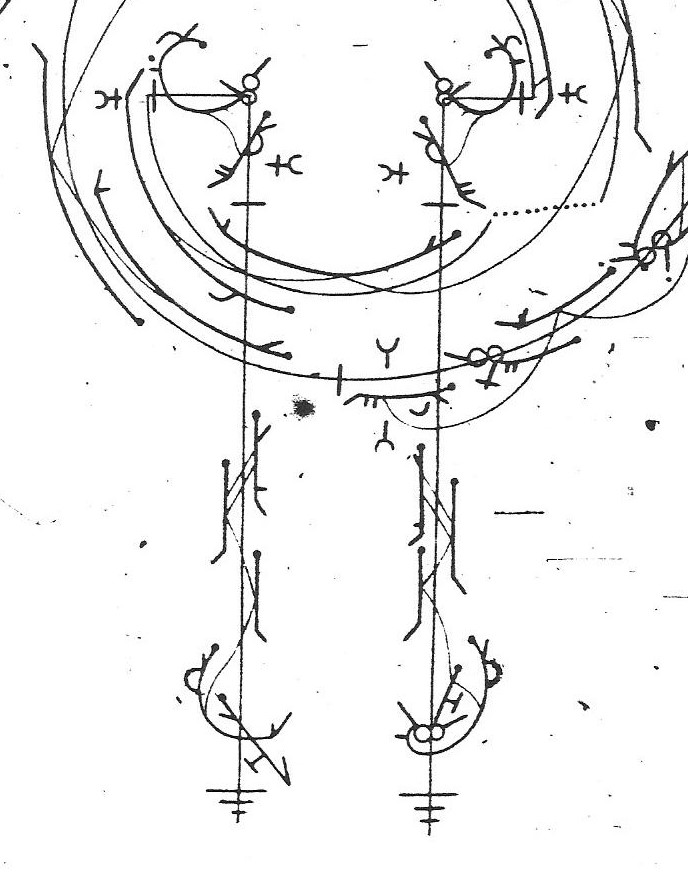

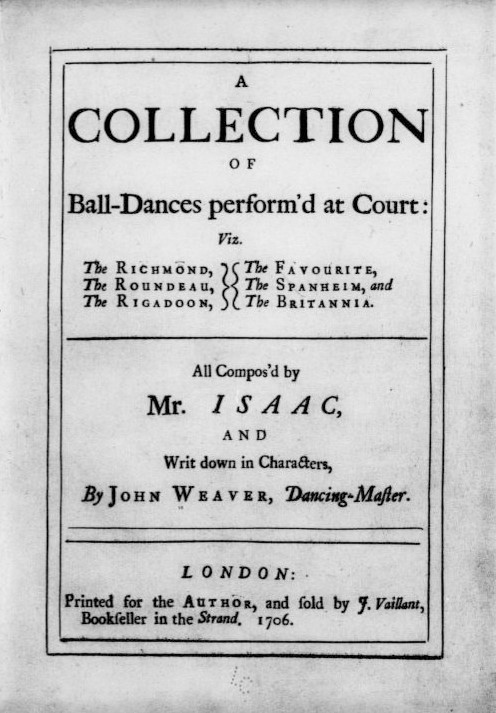

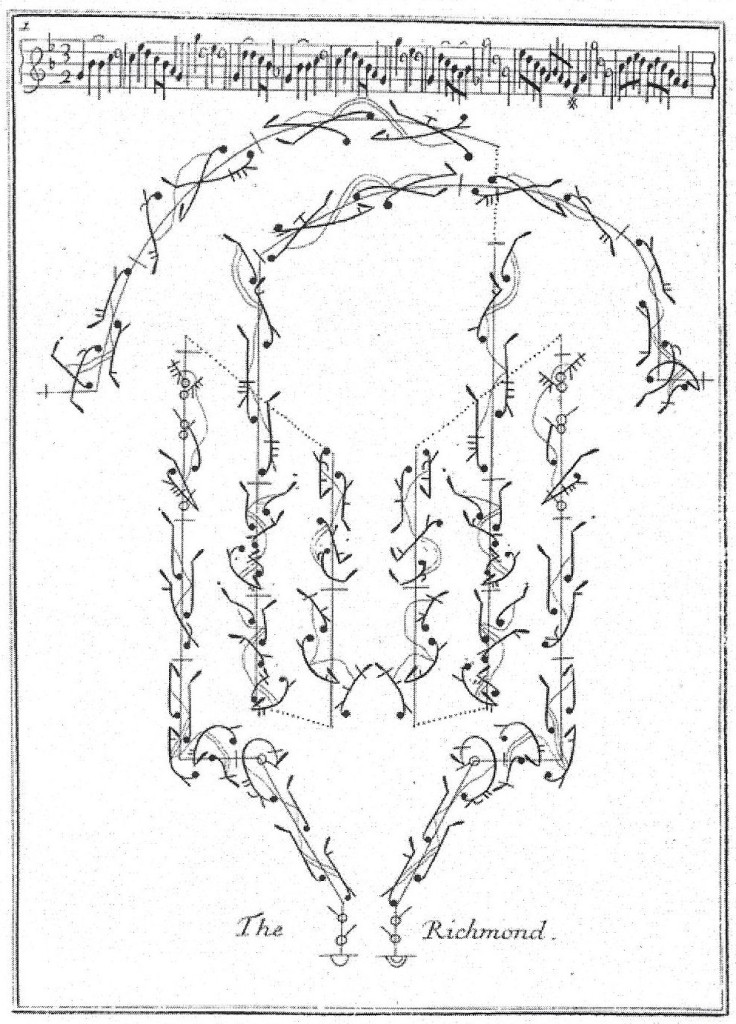

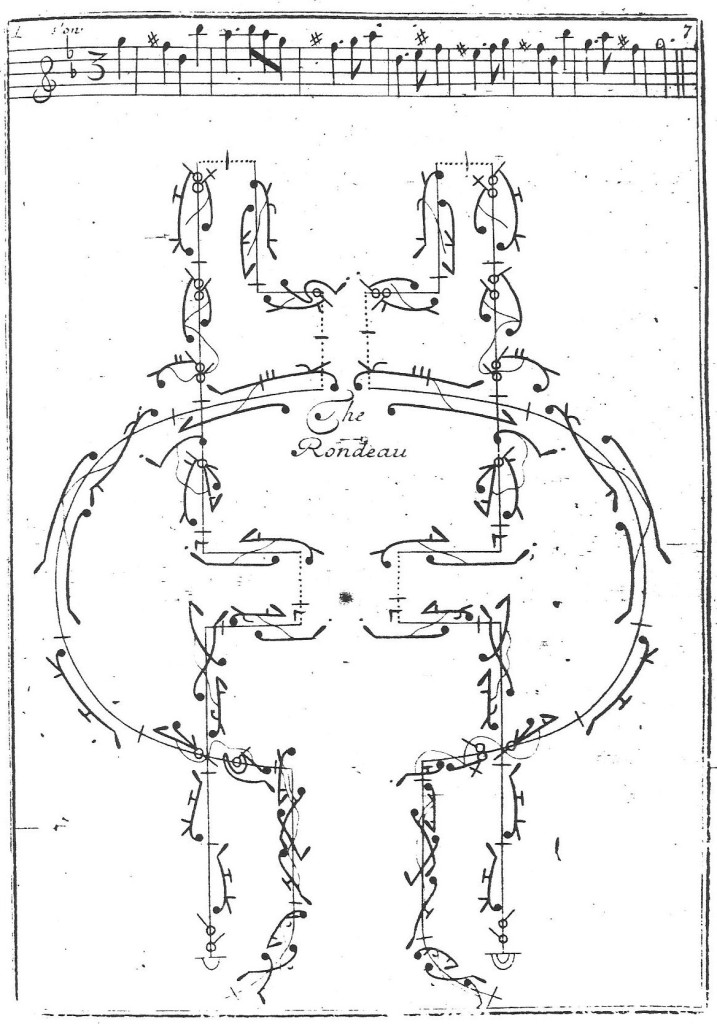

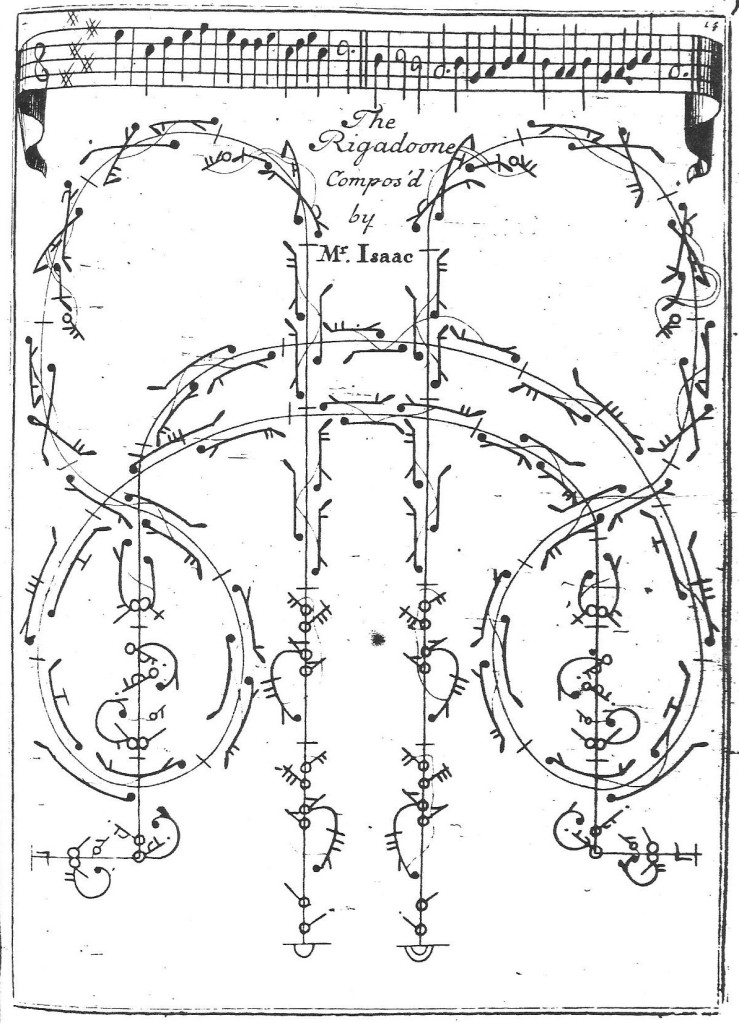

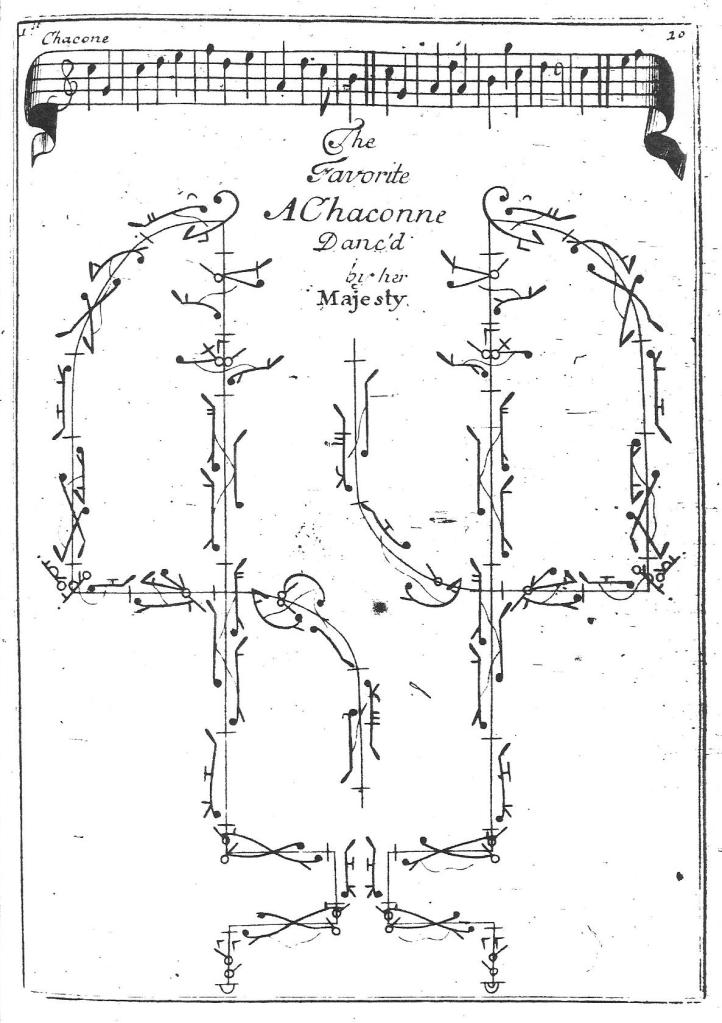

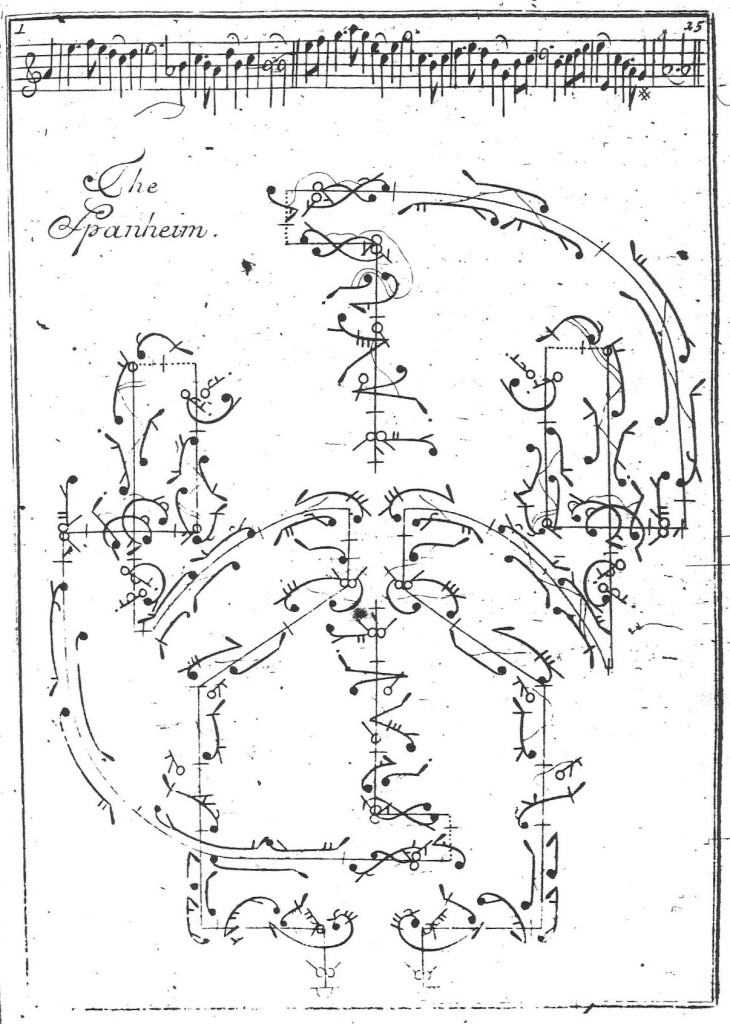

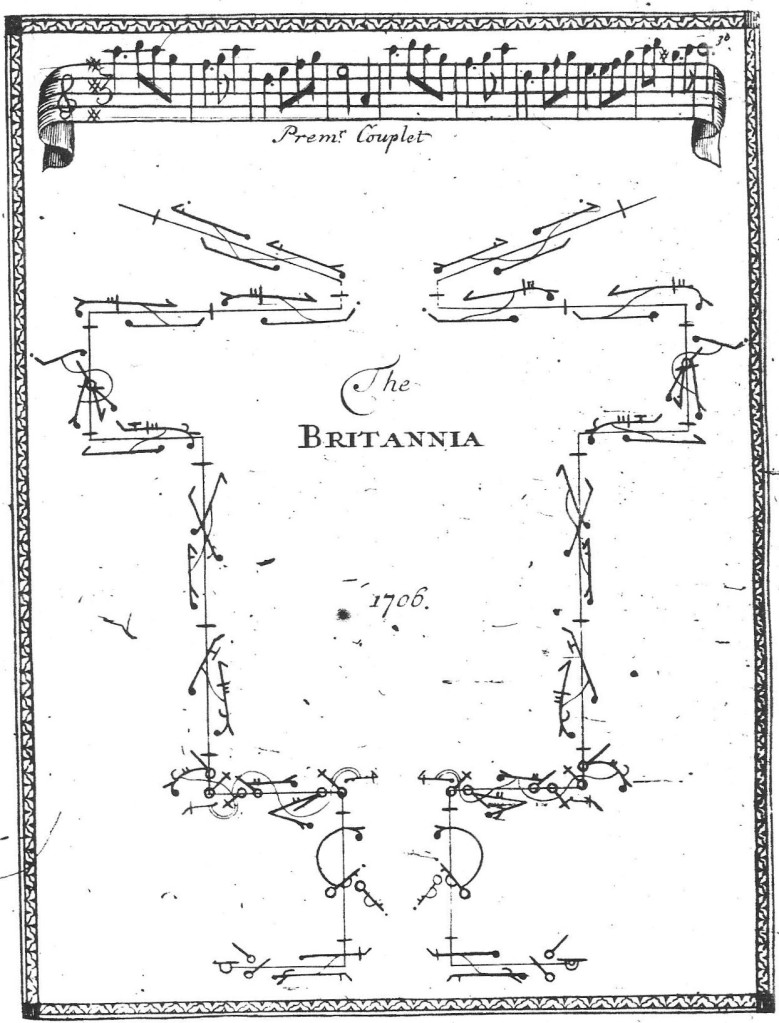

The Prince of Wales’s Saraband, as notated, is ostensibly an undemanding ballroom dance of 48 bars of music with the familiar AABB musical structure (A=10 B=14). The choreography is divided between four plates of notation (which by this time was Pemberton’s regular practice and probably reflects the expense of paper for printing). Plate 1 records the two A sections (20 bars of dance and music) and plate 2 the first B section. Plate 3 has bars 1 – 8 of the second B section and the dance ends on plate 4 with its final 6 bars. This division of the last section of the dance between two plates is dictated by the circular figures traced, which need to be shown separately so that they do not overlap, but also respects the musical phrasing. The layout on each plate may also reflect Pemberton’s aesthetic preferences – his notations for Isaac and L’Abbé include some of the most beautiful examples of this highly specialised genre of engraving.

Closer analysis of the notation reveals that this duet has some complexities and that it demands immaculate style and technique if it is to make an impact. Reconstructing the dance raises a number of questions about those aspects that are not notated – in particular arm movements and the use of the head. In all of these notated ballroom dances, the attention of the two performers seems to be divided between the presence (the guest of honour), each other and the surrounding audience. How much do we really know about the conventions that governed the performance of such dances, either at court or on stage, which should inform our dance reconstructions?

The Prince of Wales’s Saraband opens with a figure based around a temps de courante à deux, in which a temps is followed by a temps de courante, first on the inside foot and then on the outside foot. The notation indicates that the dancers turn their bodies towards the pointing foot on each temps, turning back towards the presence on each temps de courante. Did this mean that they turned their heads the same way or did they look steadfastly forward?

In the remaining bars of the first A section, they turn alternately towards one another and the presence but there are also opportunities to take in the surrounding audience.

The end of the dance, the steps and figures of the its last six bars on the final plate, has the dancers face the presence side-by-side for three bars travelling sideways away from each other and back again. They then turn to perform a pas de bourrée directly upstage, followed by a variant on the pas de bourrée vîte curving away from each other and coming face to face briefly before a coupé into their final réverence.

I can’t help wondering if this sequence was created, in part, to allow the dancers to acknowledge the audience that surrounded them before they made their final honours. The performance of The Prince of Wales’s Saraband at Drury Lane was part of a benefit for Mrs Booth, when some of the audience may have sat around the dancers on the stage (almost as they would have done in the ballroom) as well as in the auditorium. There is no evidence that Queen Caroline herself attended, but the royal box at this period would have been directly opposite the stage in the centre of the first tier just above the pit, providing the dancers with a specific focus.

The step vocabulary of this dance is dominated by the pas de bourrée, with and without a final jetté, extending to the pas de bourrée vîte. There are also a number of variants of the coupé, including the coupé sans poser and the coupé avec ouverture de jambe. It is interesting that, throughout, L’Abbé uses the jetté and not the demi-jetté in pas composés. These add energy and prevent the dance from becoming languid. He also likes to pair steps, although where he repeats these pairings he often introduces an element of variation the second time.

One sequence, on the second plate within the final bars of the B section, is noteworthy and quite challenging to perform.

L’Abbé introduces an element of suspension, in the opening coupé sans poser with a one-beat pause (which comes at the end of the preceding musical phrase), before a pas composé which demands unhurried speed – a pas plié, changement and coupé soutenu to fourth position with a quarter-turn. There is then a coupé avec ouverture de jambe (also with a one-beat pause) before the pas composé is repeated. This sequence ends with another coupé avec ouverture de jambe and a pause, before the B section is completed with two pas balancés.

The Prince of Wales’s Saraband was first performed on stage by Mrs Booth (née Hester Santlow), with whom L’Abbé had worked over many years and for whom he had created several notable choreographies. Could this ostensibly simple, yet demanding, ballroom duet have been created with and for her, intended specifically for performance at her benefit?

Further Reading:

Moira Goff, ‘Edmund Pemberton, Dancing Master and Publisher’, Dance Research, 11.1 (Spring 1993), 52-81

Moira Goff, The Incomparable Mrs Booth (London, 2007), pp. 138-139.