I have written about Pecour’s 1701 duet Aimable Vainqueur in at least three posts. This popular dance was mentioned in Favourite Ballroom Duets and Famous French Ballroom Dances. In Aimable Vainqueur on the London Stage, I looked at one strand of the performance history of The Louvre – the title by which Aimable Vainqueur was known in London’s theatres. In this post, I will look at the process of reconstructing the dance, as I have been doing just that using John Weaver’s version of the notation (titled The Louvre), which he included in the second edition of Orchesography in 1722. This is the version I will use for my exploration here.

The Louvre (Aimable Vainqueur) is a loure to music from André Campra’s 1700 opera Hésione. I don’t know whether London audiences knew that, possibly not as they were unlikely to have heard of the opera, but they must have appreciated the tune or the dance would not have survived in the entr’acte repertoire as long as it did. The music in Weaver’s version, as in Feuillet’s original of 1701, has the time signature 3 and the dance notation has one pas composé to each bar of music. Other loures, including the first part of Mr Isaac’s ball dance The Pastorall of 1713, have music in 6/4 with two pas composés to each bar of music on the dance notation. I will return to the relationship between the dance and the music later.

Weaver’s notation has some minor differences from Feuillet’s original, which suggest that he derived his version from Richard Shirley’s notation of the dance, published in London in 1715. Weaver copied Shirley’s floor patterns on the second plate as well as some of Shirley’s notations of individual steps – and he repeated some of Shirley’s mistakes. I assume that Shirley had access to Feuillet’s notation and either he, or possibly his engraver, made the changes. The Louvre has six plates of notation, with the dance divided between them in a way which reflects the music’s structure and phrasing. The music is AABB (A=14 B=24) and plate 1 has the first A, plate 2 has the second A, plate 3 has bars 1-8 of the first B, plate 4 has bars 9-24 of the first B and the second B section is similarly divided between plates 5 and 6.

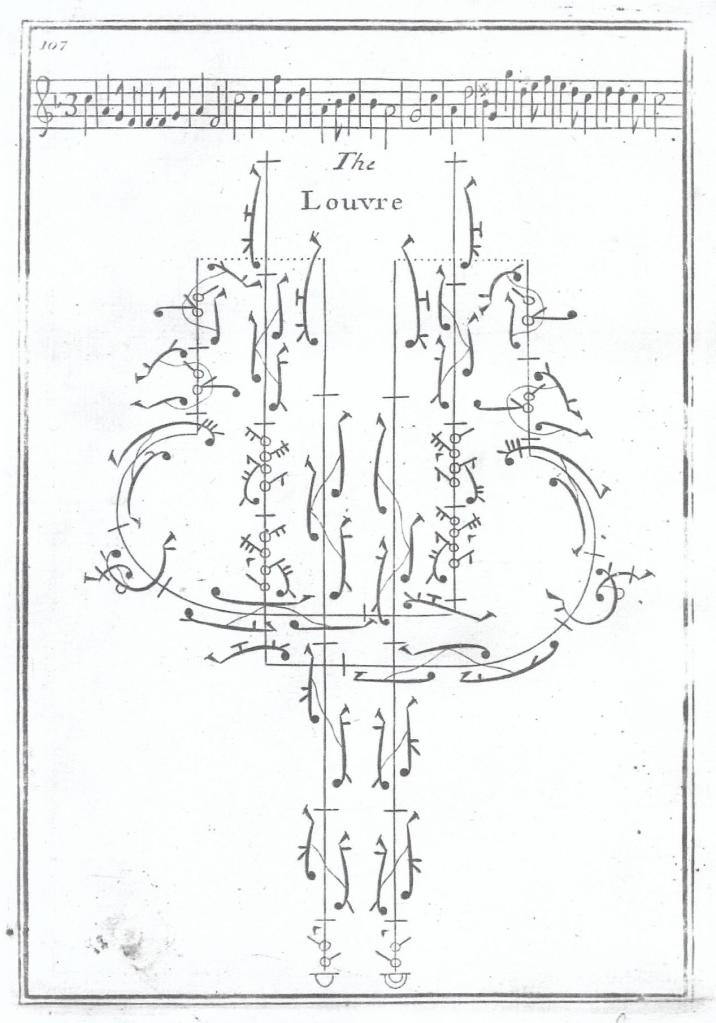

The notation is clearly set out, although it is not without mistakes and the floor patterns do not always accurately reflect the spatial relationships between the two dancers. Regular users of such notated choreographies will know that it is not possible to entirely reconcile the patterns on the page with those to be performed within the dancing space. Here is the first plate of Weaver’s notation.

All the steps of The Louvre are from the basic vocabulary of baroque dance. The pas de bourée is most often used and the coupé appears in a number of different versions, including coupé simple, coupé à deux mouvements, coupé avec ouverture de jambe and coupé sans poser le corps. Pecour’s figures and step sequences have a classical simplicity (a feature of much of his choreography), although I can’t help feeling that Aimable Vainqueur may have been expressive rather than abstract in performance. The dance takes its title from the first words of an air sung by Venus in act 3 scene 5 of Hésione. The tune was used in the opera for a dance by ‘Ombres de Amans fortunéz’, the shades of happy lovers. At the Paris Opéra, the leading dancers were Claude Ballon and Marie-Thérèse Subligny and it seems unlikely that the choreography they performed closely resembled the ballroom duet created by Pecour for performance before Louis XIV at Marly by several pairs of courtiers – although the two may well have shared some passages. I have to admit that, when I am trying to reconstruct notated dances, it is important that I know about the context for both the music and the dance to help with my interpretation.

The Louvre is in mirror symmetry, except for the last 16 bars of the first B section and bars 9 to 18 of the second B in which the dancers are on the same foot and so in axial symmetry. The sequence within the first B section is of particular choreographic interest and I will analyse it in some detail.

The duet begins conventionally, with the couple side by side and the woman on the man’s right for a passage which travels directly towards the presence. I will use some stage terms to delineate the dancing space, although these are not really appropriate for the ballroom. The dance begins with two coupés à deux mouvements, followed by a pas de bourée and a tems de courante. The sequence is simple but nicely varied rhythmically and calls for a pleasing succession of arm movements. Fewer than a third of the steps in The Louvre are directed towards the presence, although it is apparent that the dancers remain mindful of it throughout – as they would have needed to be both at the court of Louis XIV and on the London stage. The next figure begins with a variant of the pas de bourée en presence, which allows the couple to acknowledge each other for the first time. Then, after another variant of the en presence, they curve away with a contretemps which moves first sideways and then forwards. I am beginning to wonder if such steps, so early in a duet, were a commonplace intended to allow the dancers to address those who surrounded the dancing space, whether in the ballroom or on stage. In The Louvre, the dancers turn back to face the presence, cross (with the woman upstage of the man) and then travel towards the presence again to complete the section with a pas de bourée and a tems de courante.

The second plate (the A repeat) uses much the same vocabulary of steps, although the dancers begin by turning to face one another and travelling sideways rather than forwards. They turn to face the presence for a few steps and then curve away from each other, turn to face and then curve away again before turning to face on the last bar.

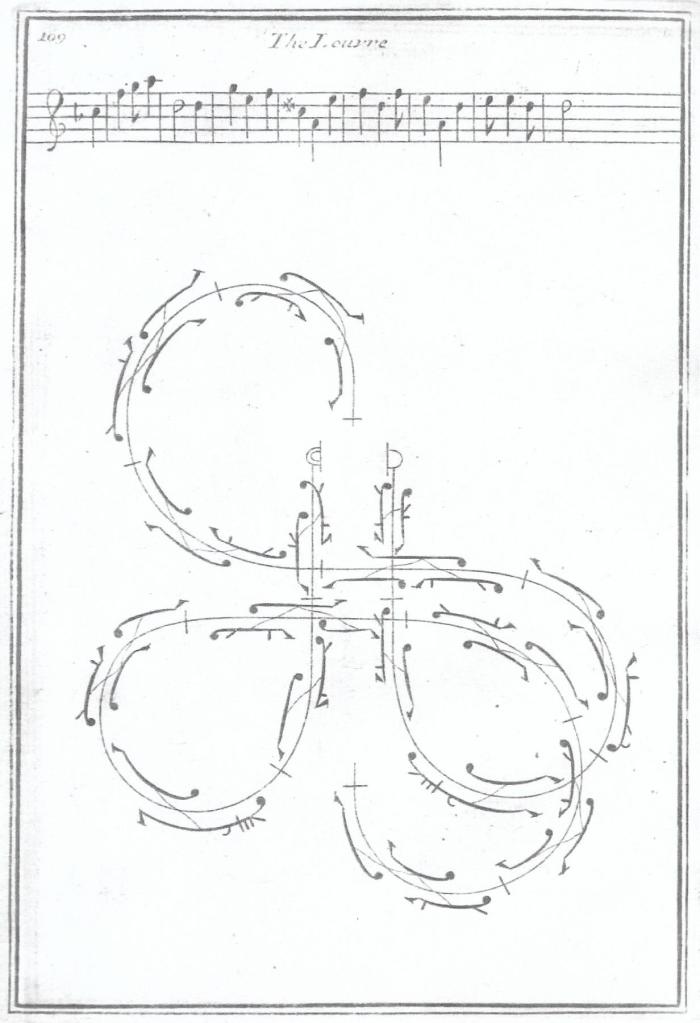

Plate 3 begins the B section with the dancers again travelling sideways upstage. Pecour then gives them each a double loop figure, in opposite directions but still in mirror symmetry. They pass one another across the stage, the woman upstage of the man, and end their second loop facing each other up and down the dancing area. The man has his back to the presence. This sequence of 8 bars (five of which are pas de bourée) raises some questions about which way the dancers’ heads turn and where they direct their gaze as they move through the figure. As they approach each other in the fourth bar, before they cross, do they look at each other rather than over their raised opposition arm (which would result in the man looking at the woman and the woman looking away from him)? In the fifth bar, in which they meet and then pass, do they both look over the raised arm towards the presence? Here is plate three of the dance, to give an idea of what might be happening.

In many ballroom choreographies there must surely have been a continual interplay between the dancers and their spectators, as they regarded each other, looked towards the presence or acknowledged members of the surrounding audience.

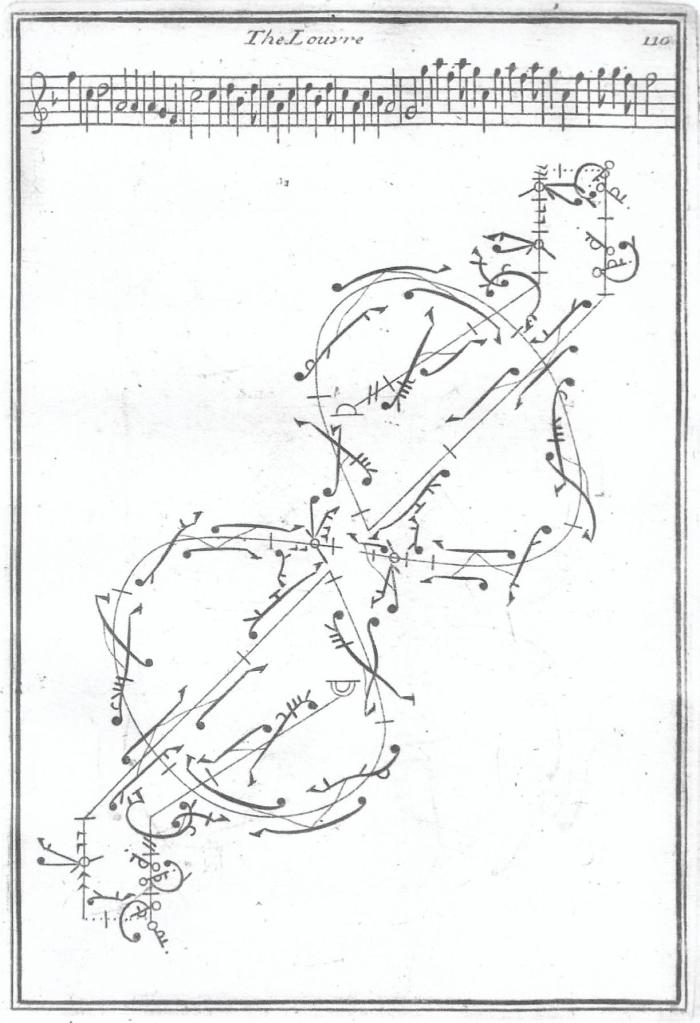

The last 16 bars of this first B section are on plate 4. They are surely the heart of this choreography, so I will explore the steps and figures in some detail. Here is the notation.

The dancers begin facing one another up and down the room and the man has his back to the presence. The couple keep to their own areas of the dancing space throughout. The step vocabulary is more varied than it has been, with the addition of half-turn pirouettes and balancé. I am not a musician, but much of the music for The Louvre seems to fall into 2-bar phrases, perhaps reproducing the 6/4 time signature found in other loures, which can seem like a call and response. This idea is clearly evident in this section of the choreography. First, the woman dances away from the man on a diagonal, with a contretemps and a coupé avec ouverture de jambe, turning her back and then turning again to face downstage (she could be looking towards him over her raised arm). She changes feet as she begins the contretemps, so that the symmetry becomes axial. The man waits as she does her steps and then responds by doing the same, ending facing upstage again. They then dance together for 4 bars, but the woman does two half-turn pirouettes followed by balancé, while the man does the balancé first and then the pirouettes. This little 8-bar sequence can surely be made expressive, in harmony with the dance’s original title Aimable Vainqueur. Was it part of Pecour’s choreography for the stage? The couple then travel towards one another on the diagonal with a pas de bourée and a tems de courante (echoing earlier pairings of these steps) before circling away and then coming to face one another across the dancing space. They do another balancé, but the man adds an extra step forward, returning to mirror symmetry.

The next figure, using the first 8 bars of the second B section, has the dancers tracing mirror-image figures of eight (although the notation blurs the pattern). They begin with jetté-chassés, followed by two pas de bourée, then jetté-chassés again and a pas de bourée followed by a coupé to first position facing one another.

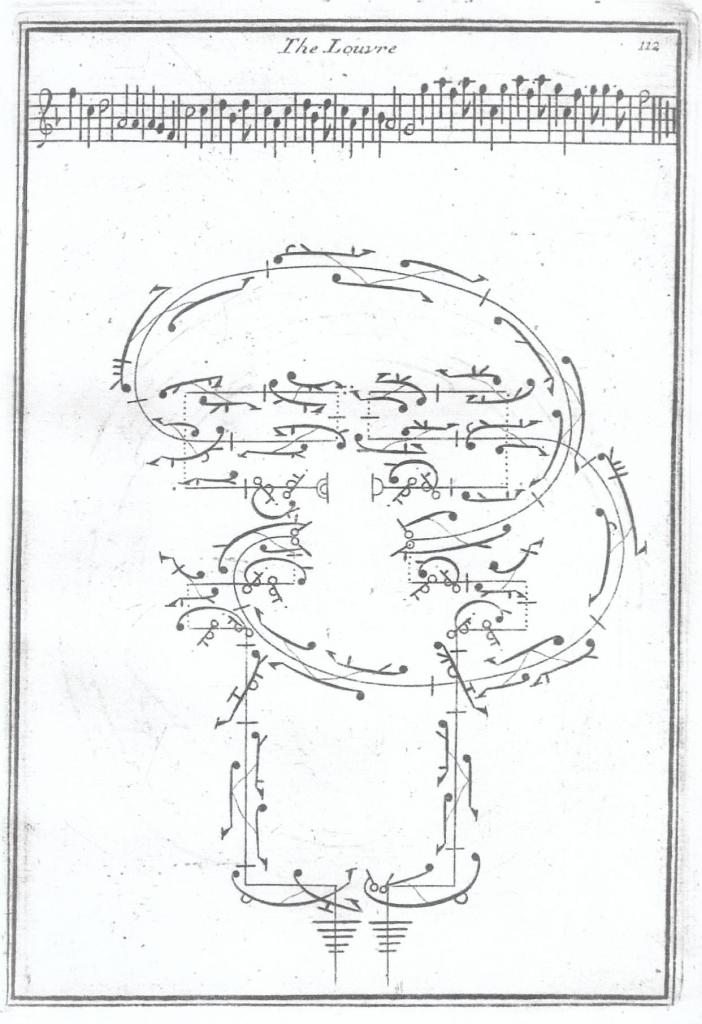

In the last 16 bars of the dance, Pecour introduces some fresh choreographic devices. Here is the final plate of The Louvre.

The dancers turn away from each other, the man facing the presence and the woman with her back to it, with a quarter-turn pirouette followed by a demi-coupé sans poser le corps. They have returned to axial symmetry with their pirouettes. They travel sideways towards each other and away again, with a varied series of coupés. Throughout this sequence the man faces the presence while the woman faces upstage. They curve away from each other, the woman passing directly in front of the presence while the man is further upstage, and come to face one another again, having changed sides. This sequence also poses challenges on where to look and the notation does not agree exactly on the steps of the two dancers (which may or may not be a mistake). This time, they could be looking towards each other as they approach with a pas de bourée – even though this means that the woman is ignoring the presence as she dances past. The sequence finishes with a coupé to first position, preparing a return to mirror symmetry.

The last six bars of The Louvre seem to be grouped in twos: half-turn pirouette, coupé avec ouverture de jambe, in which the couple turn away from each other and perhaps look towards the presence as they each extend their downstage leg; half-turn pirouette and a quarter-turn into a tems de courante travelling upstage, during which they might look at each other; finally a pas de bourée and a half-turn into the coupé which brings them side by side ready to bow to the presence.

The Louvre is certainly susceptible to interpretative choices which can change the focus of the dance and the interplay between the dancers. There is a great deal of information within the notation, although this is not always clear. There is much that is missing, too – not only the obvious, like arm movements, and the less obvious, like épaulement and the placing of the head, but also pointers to the meaning of the choreography. Is it abstract or is it expressive? We can make choices as we both reconstruct and recreate this delightful dance and try to understand what made it so popular for so long.