One of the London stage seasons I have wanted to look at more closely is 1716-1717. It was the season that saw the first performances of John Weaver’s ‘Dramatick Entertainment of Dancing’ The Loves of Mars and Venus. I am not going to explore 1716-1717 in as much detail as I did 1725-1726, although I will pick up some of the topics I mention here in later posts.

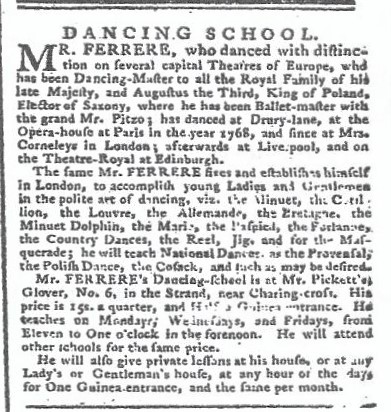

1716-1717 was the third season to follow the reopening of the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre in 1714, which ended Drury Lane’s monopoly over drama and associated entertainments. I have mentioned elsewhere that John Rich at Lincoln’s Inn Fields turned to dancing to counter Drury Lane’s far more experienced acting company. His success forced Drury Lane to take other genres, including dancing, more seriously so it could respond in kind. In 1715-1716, the forain performers Joseph Sorin and Richard Baxter had appeared at Drury Lane and presented a variety of entr’acte dances and two afterpieces which drew on the commedia dell’arte. I will return to the afterpieces, The Whimsical Death of Harlequin and La Guingette, on another occasion, but it may have been their success which prompted Drury Lane’s managers to look out for other similar entertainments and to engage the dancer and choreographer John Weaver for the next season.

During 1716-1717, Drury Lane offered 204 performances between September and the following August – including a summer season with 19 performances, which ran from 24 June to 23 August 1717. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields, there were 185 performances between October 1716 and July 1717 with no separate summer season. There was also the King’s Theatre, which offered a season of Italian opera between December 1716 and June 1717 with a total of six operas and 32 performances. At King’s, dancers were advertised at just three performances although they must have appeared more often.

The figures for performances with entr’acte dances are very different at the two main theatres. At Drury Lane there were 93 (including the summer season, 45% of the total), while at Lincoln’s Inn Fields there were 154 (83% of the total). Drury Lane had 10 performances with danced afterpieces and Lincoln’s Inn Fields had 12. However, Lincoln’s Inn Fields was evidently working hard to catch up, because their afterpieces were given in April and May – after Drury Lane’s in March and April.

As for the dancers, Drury Lane had 5 men and 3 women who danced regularly in the entr’actes, although the three women were also actresses. These dancers were: Dupré, Boval, Dupré Jr, Prince and Birkhead; Mrs Santlow, Mrs Bicknell and Miss Younger. John Weaver and Wade danced only in afterpieces. Dupré and Mrs Santlow were the company’s leading dancers. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields there were 7 men and 3 women as regular entr’acte dancers: Thurmond Jr, Moreau, Cook, Newhouse, Delagarde, Shaw and ‘Kellum’s Scholar’ (perhaps the dancer John Topham); Mrs Schoolding, Miss Smith, Mrs Bullock. Rich’s leading dancers were Anthony Moreau and Mrs Schoolding (although Miss Smith was most often billed among the women). There were also the Sallé children, Francis and Marie, who were a special attraction. At both playhouses there were other dancers who were only billed a few times during the season, although they may have performed more often. At the King’s Theatre, the dancers were Glover, billed as ‘De Mirail’s Scholar’ and Mlle Cerail. The Sallé childen made what was apparently a single appearance there on 5 June 1717, alongside Handel’s opera Rinaldo.

Francis and Marie Sallé were making their first appearance in London. At their first performance at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 18 October 1716, they were billed as ‘two Children, Scholars of M Ballon, lately arriv’d from the Opera at Paris’ with the additional notice that ‘Their Stay will be short in England’. They were undoubtedly the star dancers of the 1716-1717 season at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Rich even resorted to a ‘count down’ trick to increase audiences, with an announcement on 5 December 1716 that they ‘stay but nine days longer’, while 10 December was ‘the last time but one of their Dancing on the Stage during their Stay in England’. If this was true, he must have negotiated an extension to their contract for they reappeared not only on 11 December but on 15 December (their ‘last appearance’) and again, without comment, on 20 December. They then danced regularly until 10 June 1717.

Unsurprisingly, there were far more entr’acte dances advertised at Lincoln’s Inn Fields than at Drury Lane. Rich’s dancers gave 27 (6 group dances, 18 duets and 3 solos), while those at Drury Lane gave only 10 (5 group dances, 1 trio, 1 duet and 3 solos). Two of the Drury Lane dances – a solo Mimic Song and Country Dance and the group Countryman and Women – were only given during the summer season. The overlap in entr’acte dances between the two theatres was among the commedia dell’arte numbers. On 18 October, Drury Lane advertised Dame Ragundy and her Family, in the Characters of a Harlequin Man and Woman, Two Fools, a Punch and Dame Ragundy. According to the dancers billed for the performance, the Harlequin Man and Woman were probably Dupré and Mrs Santlow. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields that same evening there was Two Punchanellos, Two Harlequins and a Dame Ragonde, ‘the Harlequins to be perform’d by the Two Children’. Both dances were revivals from the previous season, probably with some changes. Drury Lane was trying to capitalise on its success with Sorin and Baxter in 1715-1716 as well as answer the Lincoln’s Inn Fields forays into commedia dell’arte.

On 22 October 1716, Drury Lane billed a Mimic Night Scene, after the Italian Manner, between a Harlequin, Scaramouch and Dame Ragonde, ‘being the same that was perform’d with great Applause, by the Sieurs Alard, 14 years ago’. The theatre’s revival of a piece from its own past (if that is what it was) was a success, for this Night Scene was given some 19 times during the season. The response from Lincoln’s Inn Fields was a Night Scene by the Sallé children, given three performances between 5 and 7 November. There had been some tit-for-tat billing of Night Scenes between the two theatres in 1715-1716, but Rich may now have felt he had other fish to fry when it came to dancing ‘after the Italian Manner’.

His focus was, of course, on the Sallé children, who together performed in a dozen entr’acte dances during 1716-1717. They gave nine duets and took part in three group dances. I have already mentioned the Dame Ragonde dance in which they performed as Harlequins and I will come to the other group dances shortly. Their London repertoire as child dancers in the late 1710s is worth closer analysis and I hope to return to it in another post. Here, I will only mention the ‘Scene in the French Andromache burlesqued’ in which Francis danced Orestes with Marie as Hermione – the play was presumably Racine’s Andromaque and the children may have been drawing on their repertoire at the Paris fairs. This was repeated at least five times during the season. They also performed a new duet, The Submission, by the London dancing master Kellom Tomlinson who was then starting out on his career. This was first given on 21 February 1717 and repeated another three times that month. The Submission is the only dance performed by Marie Sallé to survive in notation, for it was published by Tomlinson that same year. Here is the first plate.

The leading dancer and perhaps the dancing master at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Anthony Moreau, was credited with five dances in the bills and may well have been responsible for more. His most popular choreography by far was the Grand Comic Dance first performed with The Prophetess on 15 November 1716. It was advertised as the Grand Comic Wedding Dance alongside The Emperor of the Moon on 28 December but reverted to its original title when it was given on 8 April 1717. It received 21 performances in all in the course of 1716-1717 and the Sallé children were among its dancers.

Drury Lane revived two of its popular pastoral dances from the previous season – Lads and Lasses on 18 October and Myrtillo on 13 December – although neither of them were given more than a few performances, perhaps because there was no response from Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Lads and Lasses is one of those dances for which it is impossible to discover exactly who danced it at most, if not all, of its performances. Myrtillo may have deployed the same six dancers as in the previous season (Dupré, Boval, Dupré Jr, Mrs Santlow, Mrs Bicknell, Miss Younger – who were all named as entr’acte dancers at its first performance in 1716-1717). Lads and Lasses would last into the late 1720s. Myrtillo became a regular feature of the entr’acte dance repertoire at Lincoln’s Inn Fields as well as Drury Lane and lasted into the mid-1730s.

Both companies gave mainpieces with dancing this season. At Drury Lane these were Macbeth and The Tempest, while at Lincoln’s Inn Fields The Island Princess, Macbeth and The Prophetess as well as The Emperor of the Moon were performed. However, the most important productions, so far as future developments are concerned, were the afterpieces at both theatres. With these, the sequence of first performances is of interest as it shows clearly the progress of the rivalry between Drury Lane and Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Drury Lane, 2 March 1717, The Loves of Mars and Venus by John Weaver

Drury Lane, 2 April 1717, The Shipwreck; or, Perseus and Andromeda by John Weaver

Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 22 April 1717, The Cheats; or, The Tavern Bilkers

Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 29 April 1717, The Jealous Doctor

Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 20 May 1717, Harlequin Executed

These were all new productions and it is evident that Rich at Lincoln’s Inn Fields was responding to Weaver at Drury Lane. I have written about The Loves of Mars and Venus elsewhere and I will take another closer look at this ballet in due course. Rich would produce a direct response to it in 1717-1718 and there would be several Lincoln’s Inn Fields afterpieces which used the phrase ‘Loves of’ in their titles. This season, though, there was only an entr’acte dance, The Loves of Harlequin and Colombine, performed by Francis and Marie Sallé on 23 April 1717. Might this suggest that the two children had been taken to Drury Lane to see Dupré and Mrs Santlow as Mars and Venus, so they could mimic them?

The Cheats; or, The Tavern Bilkers was, of course, a direct hit at Weaver by Rich – who obviously knew of Weaver’s claim to have created a piece entitled The Tavern Bilkers some fifteen years earlier, described by Weaver some years later as ‘The first Entertainment that appeared on the English Stage, where the Representation and Story was carried on by Dancing, Action and Motion only’ (The History of the Mimes and Pantomimes, published 1728, see page 45). The Jealous Doctor was based on a new, short-lived play given at Drury Lane on 16 January 1717, Three Hours after Marriage by John Gay, Alexander Pope and John Arbuthnot. Harlequin Executed had begun as a Lincoln’s Inn Fields entr’acte dance, entitled Italian Mimic Scene between a Scaramouch, Harlequin, Country Farmer, His Wife and Others on 26 December 1716 before being renamed as Harlequin Executed; or, The Farmer Disappointed on 29 December. After some seven performances as an entr’acte dance, it became an afterpiece on 10 May 1717 and would last in the Lincoln’s Inn Fields repertoire until 1721-1722. Although there is no mention of him in Harlequin Executed until 1717-1718, ‘Lun’ (John Rich himself) took the role of Harlequin in both The Cheats and The Jealous Doctor – directly challenging Weaver as Vulcan in The Loves of Mars and Venus and Perseus (Harlequin) in The Shipwreck. All of these afterpieces were, of course, laying the foundations for the new genre of English pantomime that would emerge over the next few years. This satirical print depicts how unsettling that would be for serious drama on the London stage. ‘Lun’ as Harlequin takes centre stage.

![Chacone of Amadis 1 L'Abbé, 'Chacone of Amadis', A New Collection of Dances, [c1725], plate 1](https://i0.wp.com/danceinhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/chacone-of-amadis-1.jpg?w=320&h=381&ssl=1)

![passagalia-1 L’Abbé, ‘Passagalia of Venüs & Adonis’, A New Collection of Dances, [c1725], plate 1](https://i0.wp.com/danceinhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/passagalia-1.jpg?w=297&h=381&ssl=1)