Next year marks the 300th anniversary of John Weaver’s The Loves of Mars and Venus. His ‘dramatic entertainment of dancing’ was first performed at the Drury Lane Theatre on 2 March 1717.

John Weaver, The Loves of Mars and Venus, detail from title page

Why is this often overlooked dance work so important? It is the first modern ballet – the first theatrical work to tell a story and represent its characters solely through dance, mime and music. Unlike all the ballets that had come before it, including the much celebrated French ballets de cour and English masques, there were no spoken or sung words. The Loves of Mars and Venus was a dance work, nothing more and nothing less.

Weaver’s ballet tells the story of the love affair between the goddess Venus and Mars, the god of War, and the revenge enacted on them by her husband Vulcan. It draws on classical mythology, but contemporary passions abound. Despite Weaver’s appeal to the revered performances of the ‘mimes and pantomimes’ of classical antiquity, who he wished to emulate, his ballet was a thoroughly modern work in tune with the sophisticated comedies of his own time.

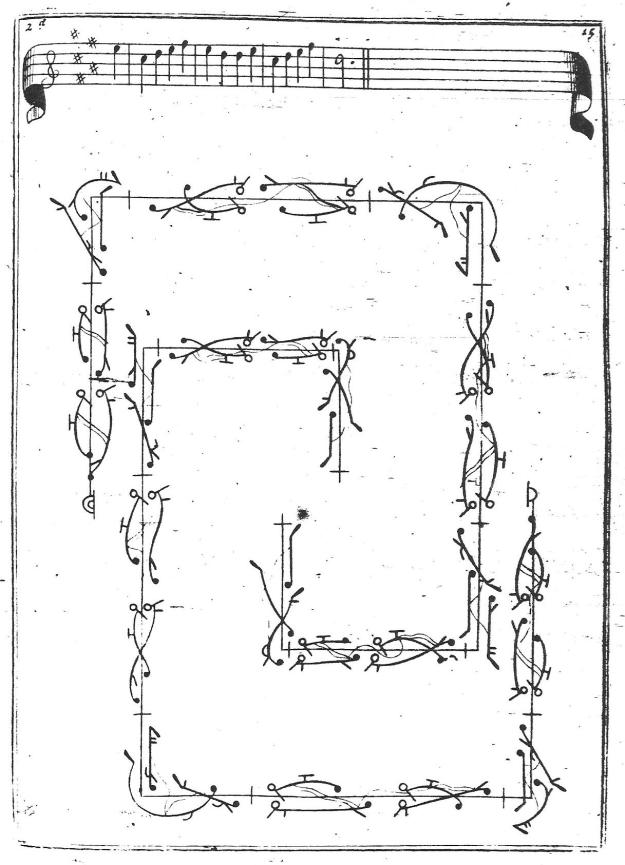

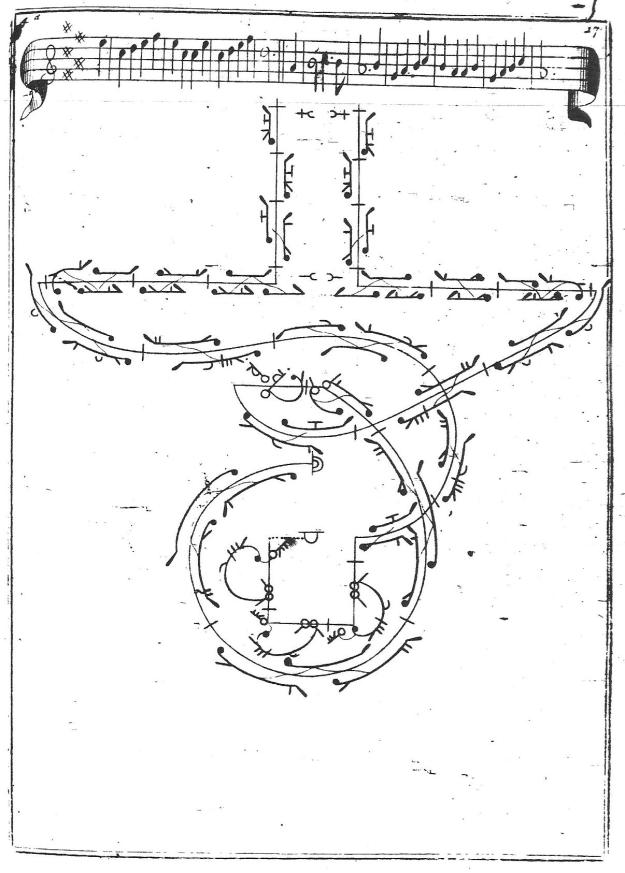

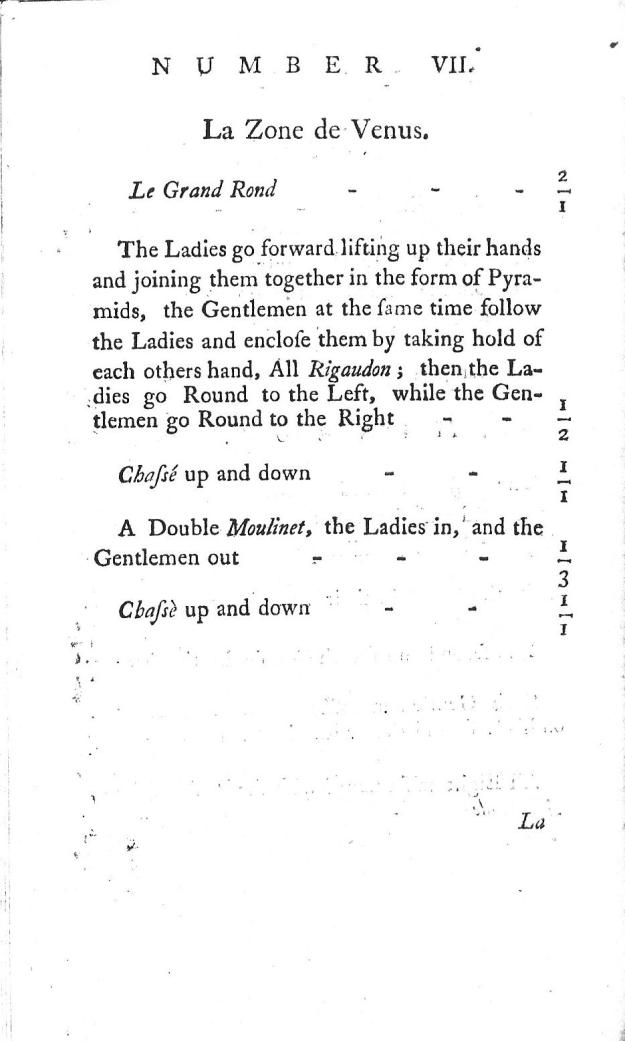

The Loves of Mars and Venus has six short scenes. Mars appears with his soldiers and performs a war dance. Venus is shown surrounded by the Graces and displays her allure in a sensual passacaille, but when Vulcan arrives she quarrels with him in a ‘dance of the pantomimic kind’. Vulcan retires to his smithy to devise revenge with the help of his workmen the Cyclops. Mars and Venus meet and, with their followers, perform dances expressive of love and desire. Vulcan completes his plan of revenge against the lovers. In the final scene, Vulcan and the Cyclops catch Mars and Venus together and expose them to the derision of the other gods, until Neptune intervenes and harmony is restored in a final ‘Grand Dance’. The entire ballet took, perhaps, about 40 minutes.

John Weaver was a dancer as well as a choreographer. He is also one of the very few dance practitioners who have written about their art. He was Vulcan. Venus was Hester Santlow, also an actress and a dancer of consummate skill and expressiveness. Mars was Louis Dupré, a virtuoso dancer who was probably French (although not Louis ‘le grand’ Dupré, with whom he is still often confused). Weaver’s bold experiment had the best dancers on the London stage.

This first modern ballet was a remarkable work and enjoyed success in its own time. It was subsequently far more influential than many realise. It may well have been seen by the young dancer Marie Sallé, who would herself later experiment with narrative and expressive dancing. Sallé, of course, influenced Jean-Georges Noverre when he came to create his ballets d’action. They led to the story ballets of the romantic period and onwards to today’s narrative dance works.

Has Weaver’s The Loves of Mars and Venus been consigned to history or can it be recovered? I will explore this innovative ballet further in later posts.