As I continue to work on baroque notated choreographies, I constantly wonder how I should perform their steps. I learned the basic baroque dance technique a long time ago and I have worked on various approaches to it over the years, with different teachers. More recently, I have had to work mostly on my own, without access to the latest thinking and practice on what the treatises and the notations actually mean, so I have many questions.

I have been learning a couple of ballroom dances that include minuets and one question in particular arose. How should the basic pas de menuet travelling forwards be performed, should it be danced smoothly or have staccato elements? It begins with a demi-coupé (essentially a plié followed by a step forward and a rise as the weight is transferred) and continues with a fleuret (another demi-coupé followed by two steps on the balls of the feet) How should the demi-coupés be performed? Should the pliés be soft and controlled or should there be a quick and somewhat sharp bend of the knees and ankles? How should the transition at the end of this pas composé be managed? Is there a sharp lowering from the demi-pointe into a plié or does the final step end on a flat foot in preparation for the bend that begins the demi-coupé? I am not going to explore the timing of this step, because I looked at this in some detail in The Pas de Menuet and Its Timing a few years ago.

When I find myself in doubt about an aspect of baroque dance technique, I generally go back to the early treatises – Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître à danser (Paris, 1725), with its translation by John Essex The Dancing-Master (London, 1728), and Kellom Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing (London, 1735). Here is what Rameau (as translated by Essex) has to say about the pas de menuet ‘of only two Movements’:

‘Having then the left Foot foremost, you rest the Body on it, bringing the right Foot up to the Left, in the first Position, and from thence sink without letting the right Foot rest on the Ground, and move the right Foot into the fourth Position, rising at the same Time on the Toes, and extending both Legs close together, as represented by the fourth Figure of the half Coupees, called the Equilibrium or Balance; and afterwards set the right Heel down to the Ground, that the Body may be the more steady, and sink at the same Time on the right, without resting on the Left, which move forwards the same as the right Foot, into the fourth Position, and rise upon it: Then make two Walks on the Toes of both Feet, observing to set down the Heel of the Left, that you may begin your Menuet Step again with more Firmness.’

The Dancing-Master, Chapter XX1, pp. 44-45.

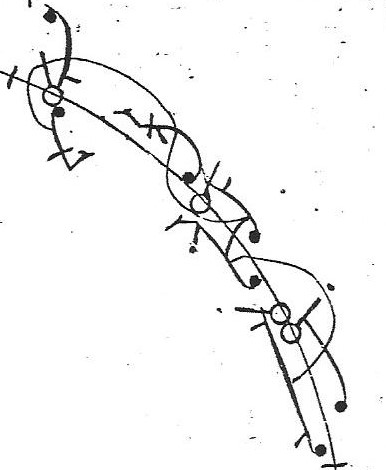

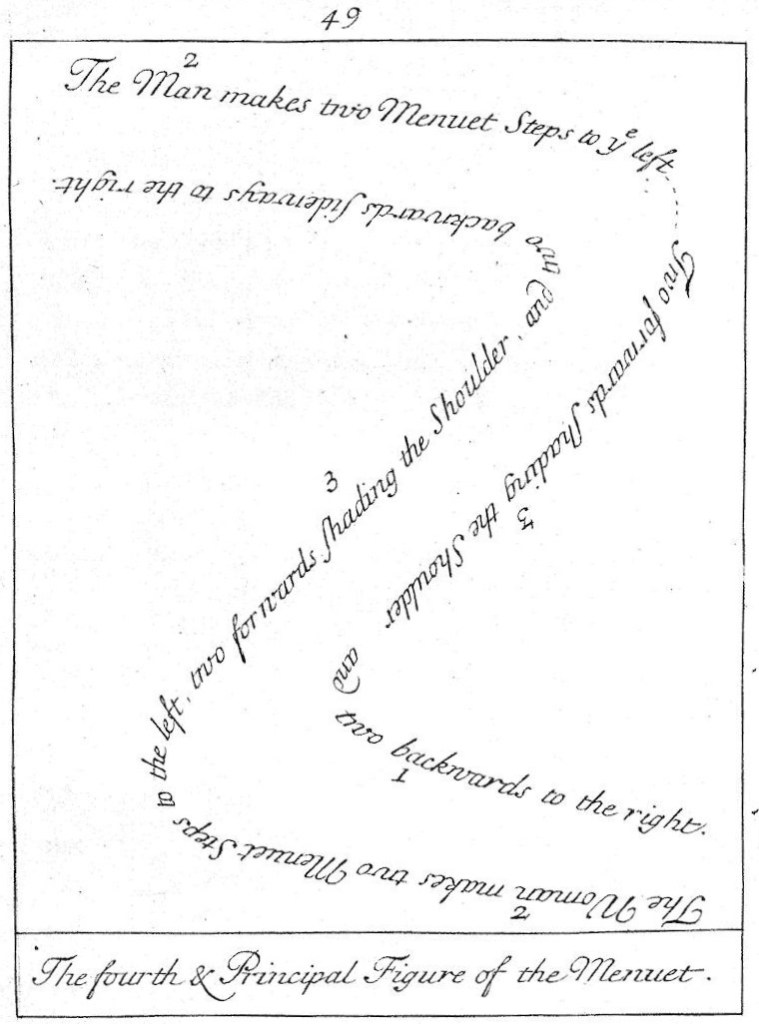

By ‘Toes’, Essex means the ball of the foot, translating Rameau’s ‘la pointe du pied’ – in both cases the meaning is made clear by the engravings that accompany the description of the demi-coupé. Here is the fourth and final one:

It is interesting that in modern ballroom dancing ‘toe’ also means the ball of the foot.

Tomlinson explains the method of performing the pas de menuet and its timing together (I have omitted some of the text relating to the timing as it is given in my earlier post):

‘The Weight of the Body being upon the left foot in the first position the right, which is at liberty, begins the Minuet Step, by making the Half Coupee or first of the four Steps belonging to the Minuet, in a Movement or Sink and Stepping of the right Foot forwards, the gentle or easy Rising of which, either upon the Toe or the Heel, marks what is called Time to the first Note of the three in the first of the two Measures, … the second Note is the coming down of the Heel to the Floor, if the Rise was made upon the Toe, but if upon the Heel or the flat Foot, in the tight Holding of the Knees before the Sink is made that prepares for the Fleuret or Bouree following, in which is counted the third and last Note of the Measure aforesaid; …

The Sink or Beginning of the Movement, that prepares for the Fleuret or second Part of the Minuet Step, … being made, there only remains to rise from the Sink aforesaid in the stepping forwards of the left Foot to the first Note of the second Measure, and first of the Fleuret or three last Steps that compose the Minuet Step; …’

The Art of Dancing. Book the Second, Chap. I, pp. 105-106.

By ‘Heel’ Tomlinson means the flat foot, allowing for those dancers who do not wish to attempt a balance on the ball of the foot.

Neither passage directly answers my questions, although Tomlinson refers to ‘gentle or easy Rising’ in the demi-coupé. In the chapter preceding that on the minuet step, ‘Of the Manner of making half Coupees’, Rameau tells his reader ‘good Dancing very much depends on this first Step, since the knowing how to sink and rise well makes the fine Dancer.’ (The Dancing-Master, Chapter XX, p. 42). I would need to look further and more closely at what both Rameau and Tomlinson say about other steps before reaching firm conclusions about how to perform the basic pas de menuet.

Before I conclude this post, there are a couple of interesting issues I would like to touch on concerning the pas de menuet à trois mouvements. Rameau describes this version as follows:

‘This Menuet Step hath three Movements, and one March on the Toes; viz. the first is a half Coupee of the right Foot, and one of the left; a March on the Toes of the right Foot, and the Legs extended: At the End of this Step you set the right Heel softly down to bend its Knee, which by this Movement raises the left Leg, which moving forwards makes a Tack or Bound, which is the third Movement of this Menuet Step, and its fourth Step.’

The Dancing-Master, Chapter XXI, p. 43.

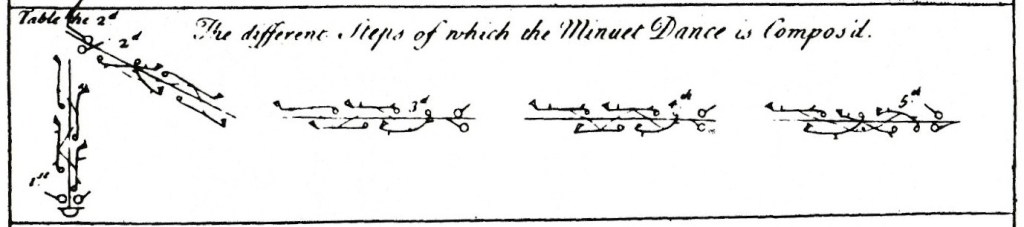

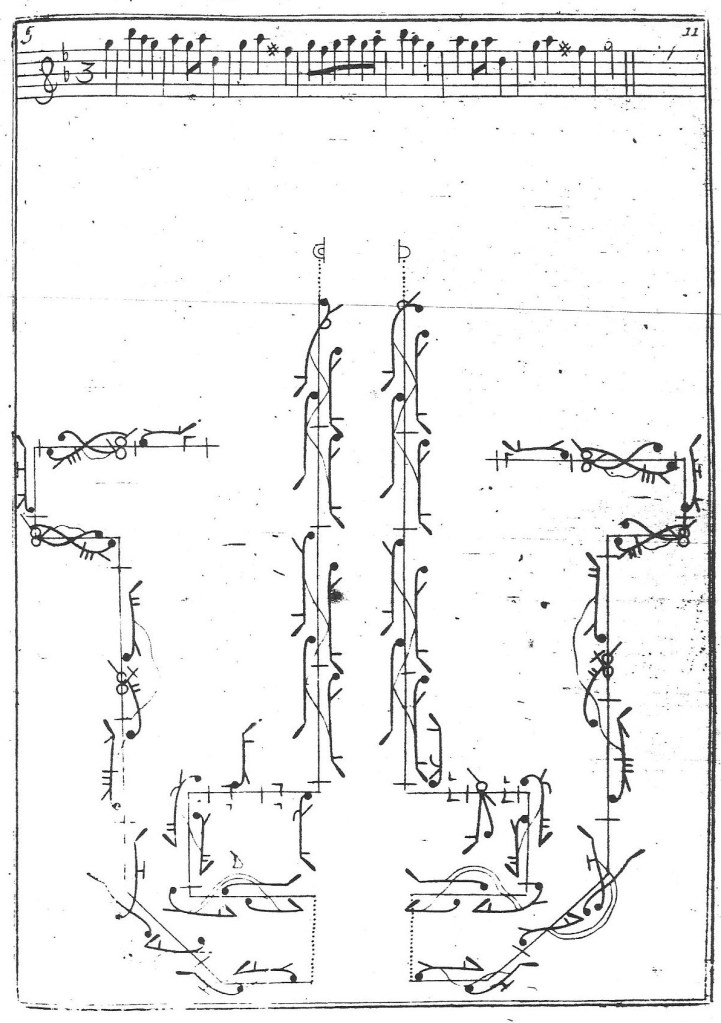

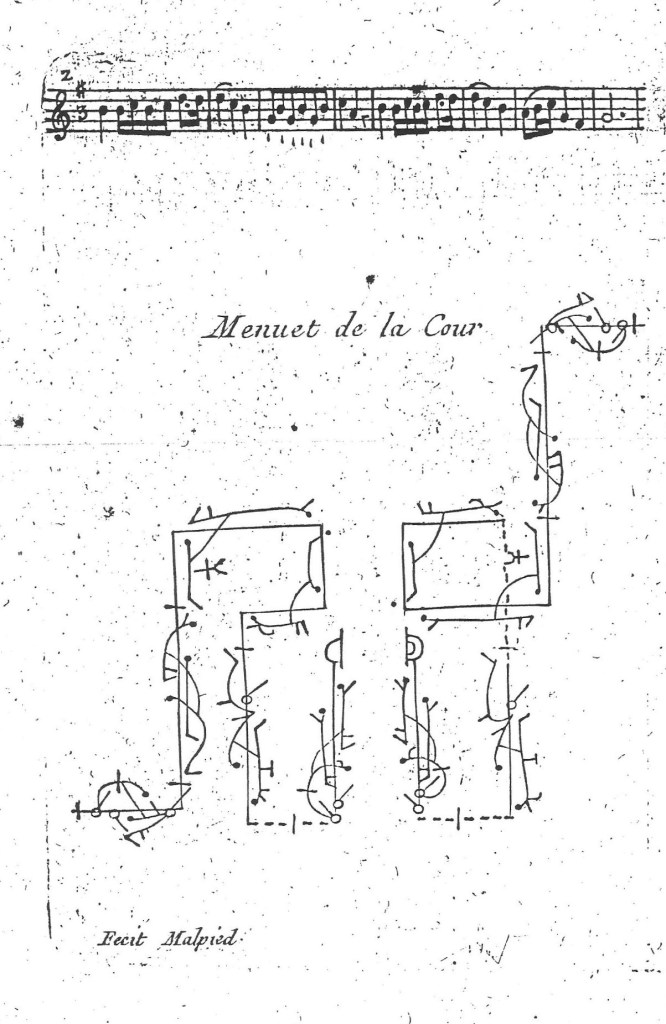

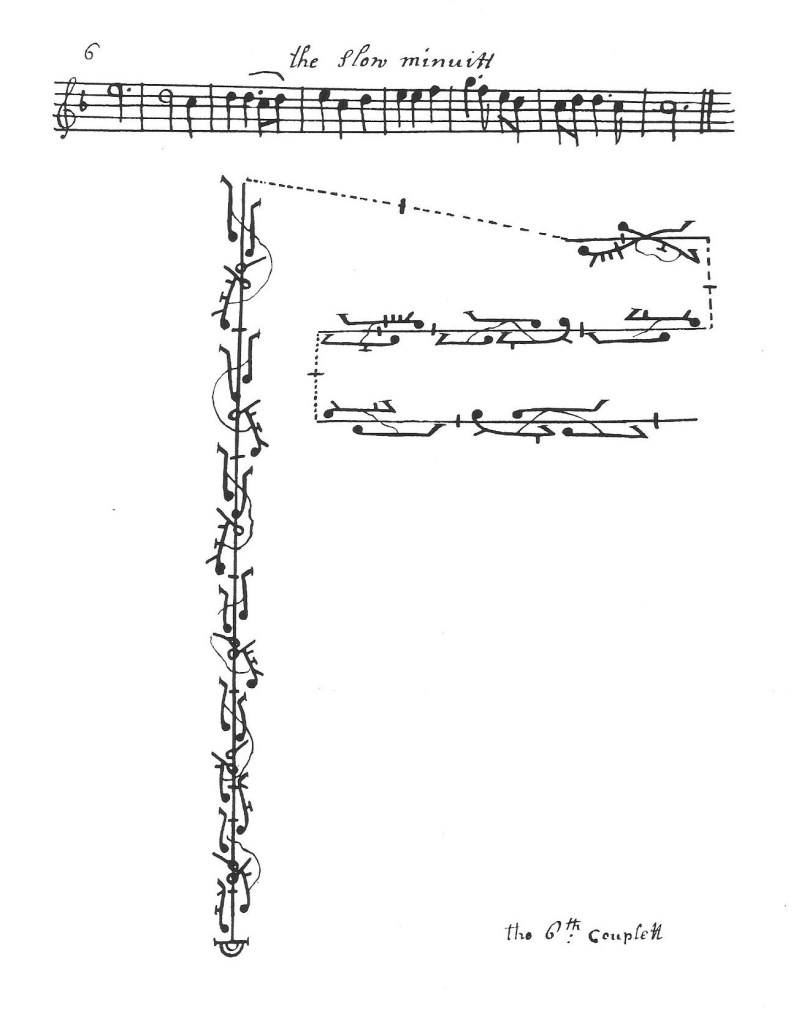

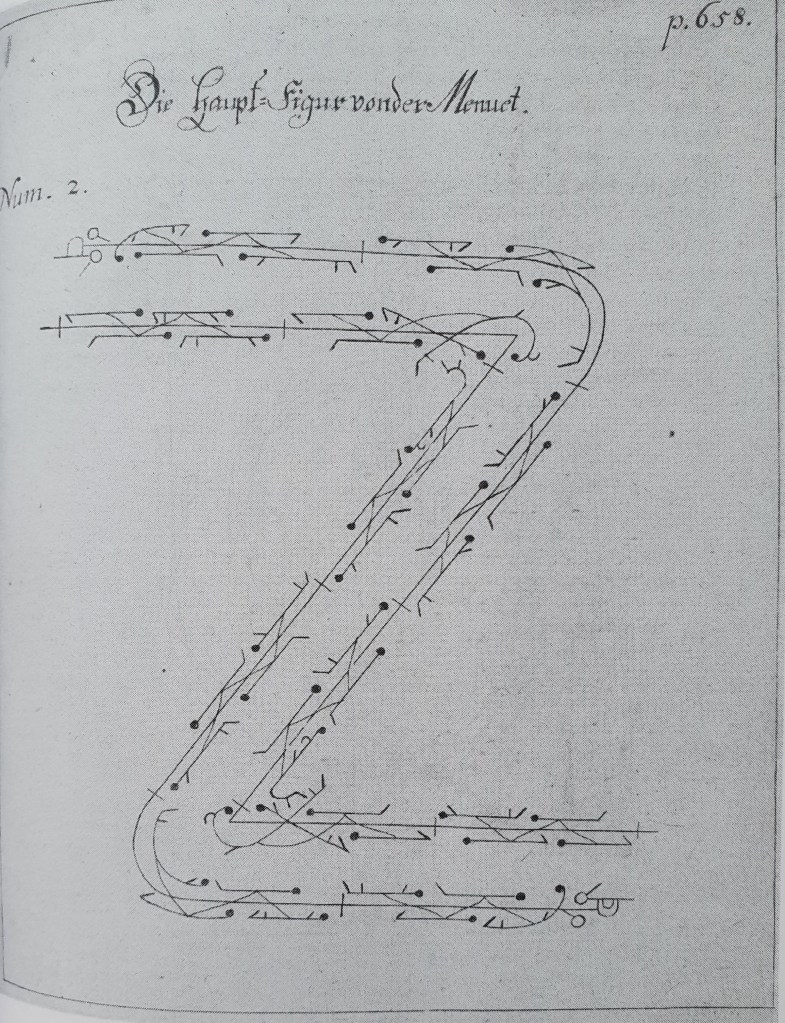

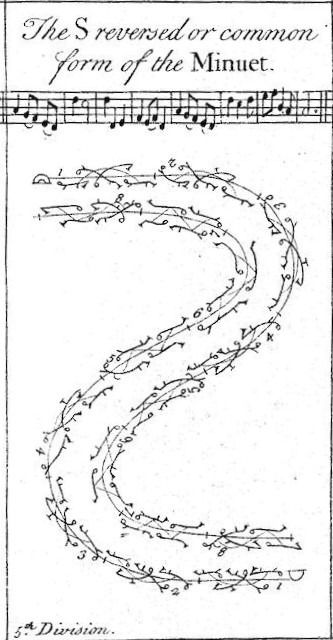

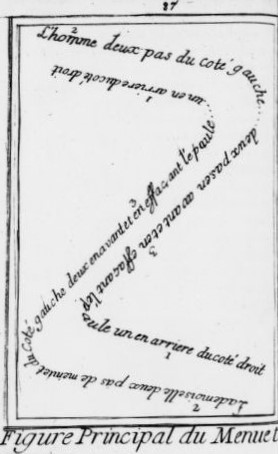

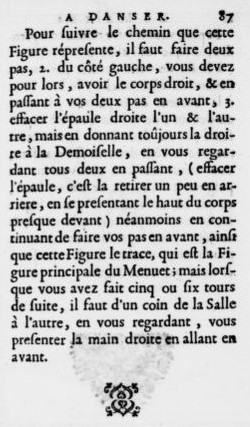

Rameau adds ‘But as this Step is not agreeable to every one, because it requires a very strong instep; for this Reason it is not so much used, but a more easy Method introduced’ (The Dancing-Master, Chapter XXI, p. 44) and he goes on to describe the basic pas de menuet. Tomlinson, writing around the same time (although The Art of Dancing was published ten years later) calls that basic minuet step ‘One and a Fleuret’ or the ‘New Minuet Step, … that is now danced in all polite Assemblies’ (The Art of Dancing. Book the Second. Chap. I, p. 104). Here are Tomlinson’s notations of his various minuet steps, from Plate O in The Art of Dancing:

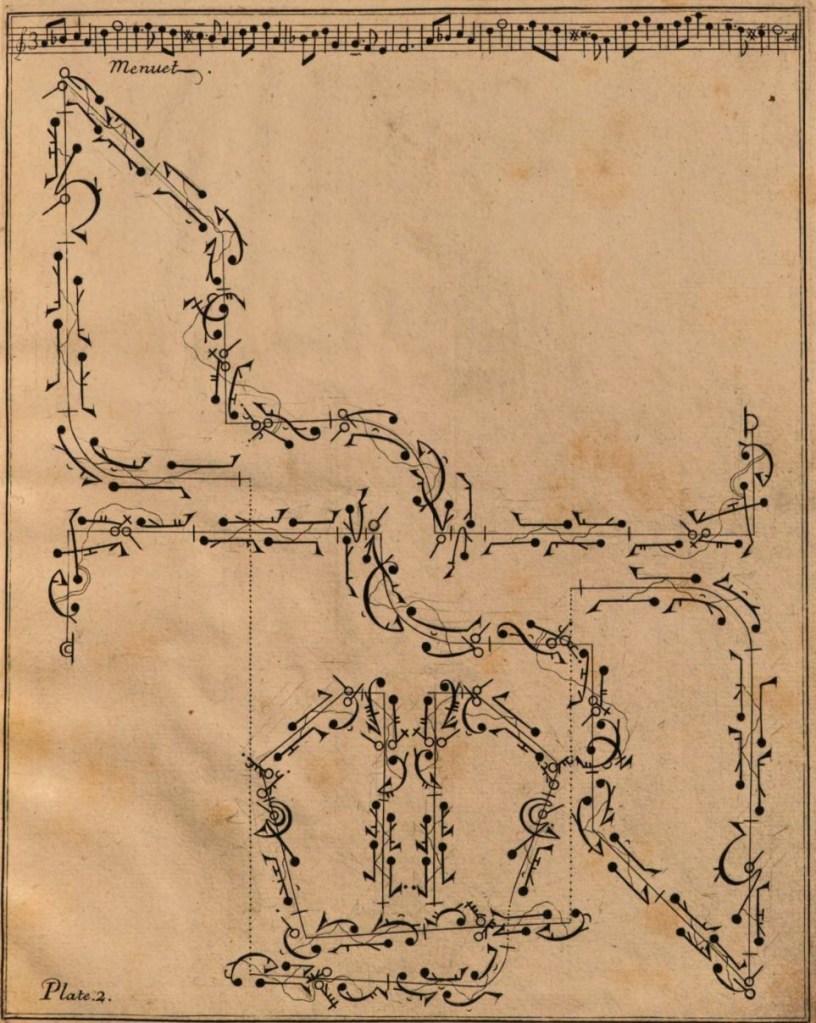

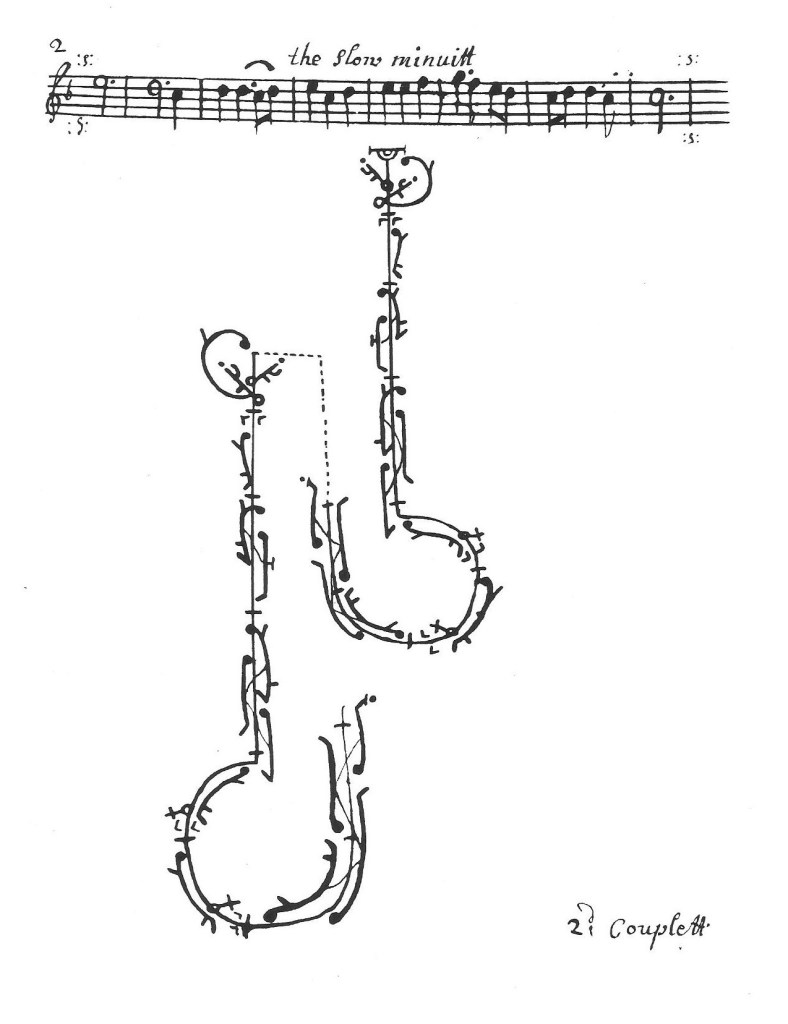

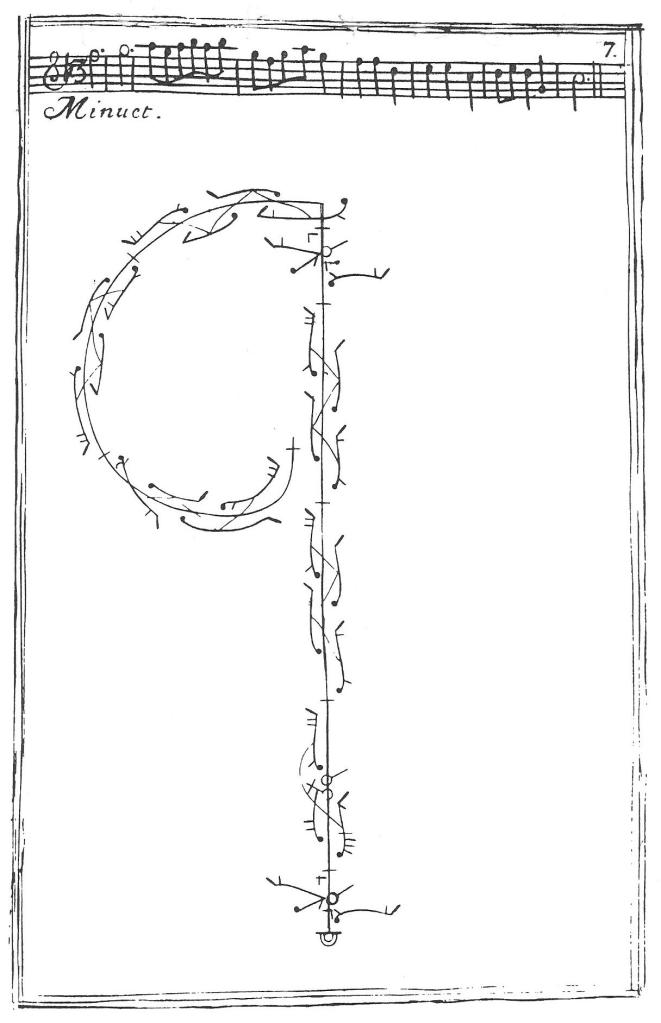

I will leave aside the additional complexities introduced when minuet steps are performed sideways to the right and the left (which can be seen in the above illustration). Nor will I consider how the pas de menuet is shown in the notated stage minuets – although the solo ‘Menuet performd’ by Mrs Santlow’ in L’Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances begins with a sequence of pas de menuet à trois mouvements.

There are several other posts about the minuet on Dance in History. The most relevant to my topic here is probably Thomas Caverley’s Slow Minuet.