One way to finance printing and publication in the 18th century was through subscriptions. Authors would solicit advance payment for their books from a circle of clients and supporters, enabling these to be printed. The subscribers would receive their copies soon after printing and there would be additional copies available for purchase by non-subscribers, often at a higher price. A list of those who had subscribed was printed for inclusion in the volume and can provide valuable information about the intended audience for the work. Several dancing masters of the period availed themselves of this funding method and I thought it would be interesting to take a look at their subscription lists.

I will start with John Weaver. His translation of Feuillet’s Choregraphie (entitled Orchesography) as well as A Collection of Ball-Dances by Mr Isaac, which he had notated, were published by subscription in 1706. Some years later, in 1721, Weaver’s Anatomical and Mechanical Lectures upon Dancing was similarly published. Who were Weaver’s subscribers and were they different for each of the three publications?

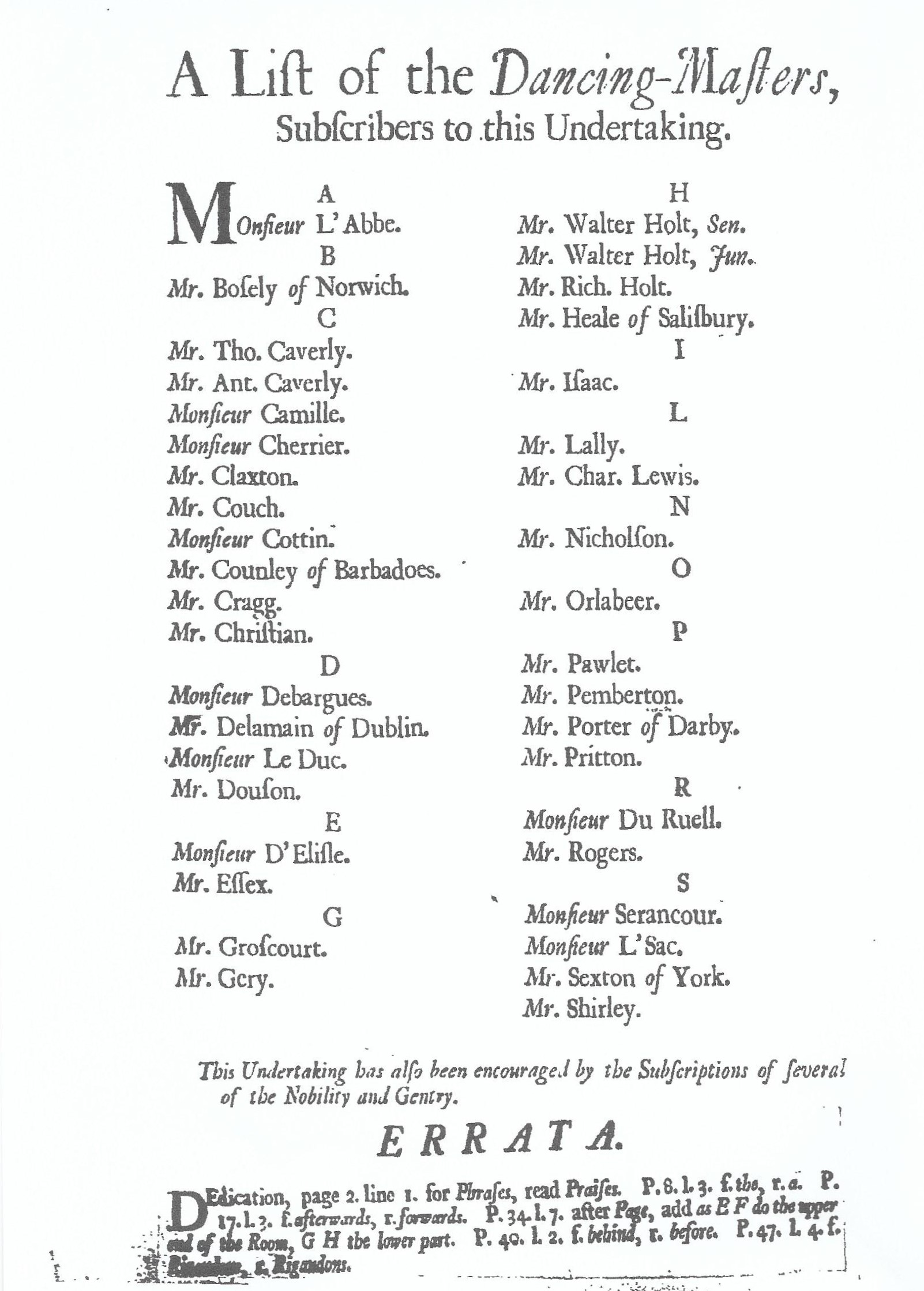

Orchesography had 39 subscribers, all of whom also subscribed to A Collection of Ball-Dances, which had a total of 47 names on its subscription list. Anatomical and Mechanical Lectures upon Dancing had only 31 names, of which only nine had subscribed to Weaver’s earlier works. The first name on all three lists is that of Monsieur L’Abbé, by virtue of his place in the alphabet, although by 1721 he was also the royal dancing master – a post which placed him at the head of his profession in Great Britain. L’Abbé was one of ten men listed with the title ‘Monsieur’ in the 1706 lists, identifying them as French. He is the only one so identified in the 1721 list. The majority of the men named as subscribers in the three lists (there were no women) were identified simply by their names, but there were a handful in all of the lists who were further identified by the place where they lived and worked. I will look at each of these groups in turn.

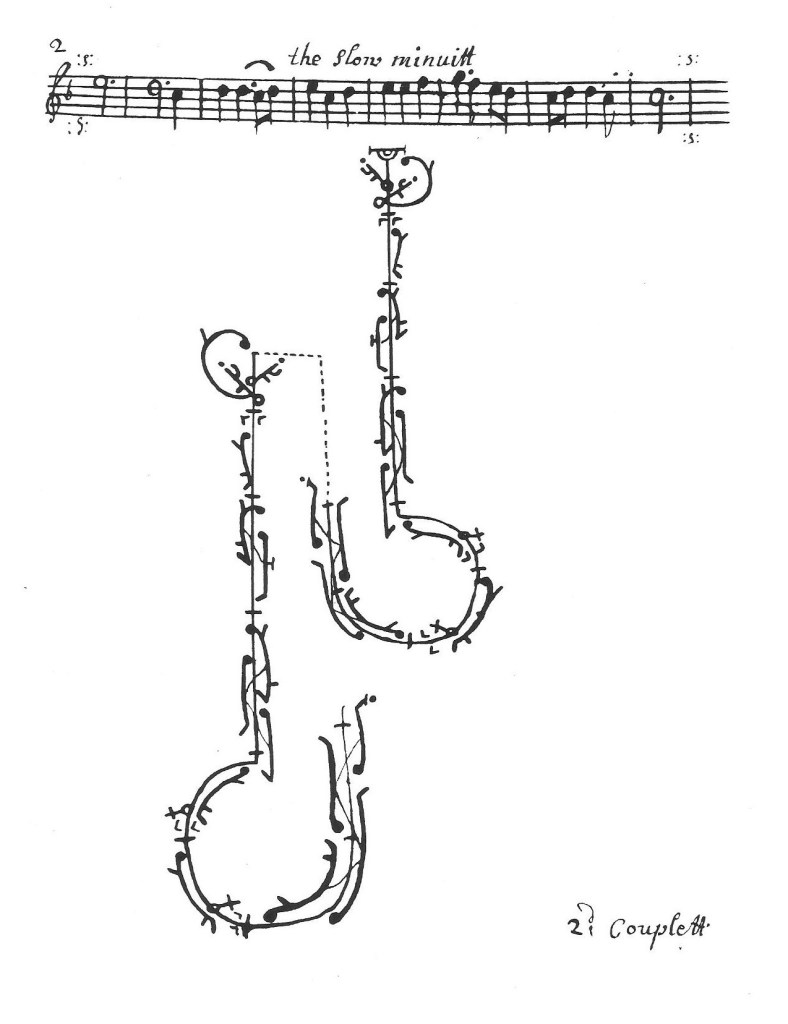

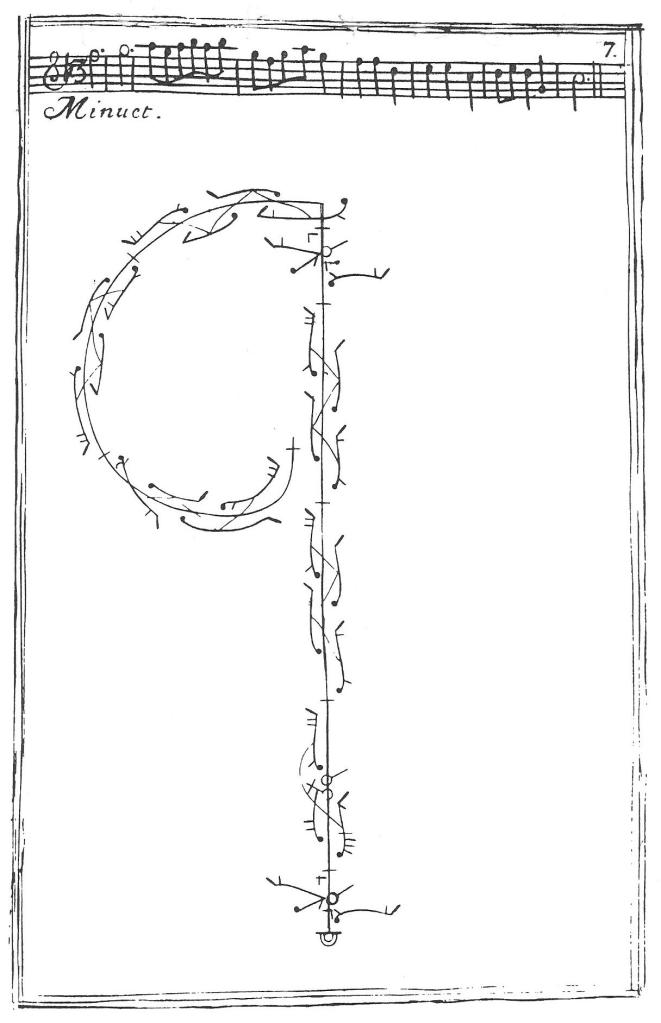

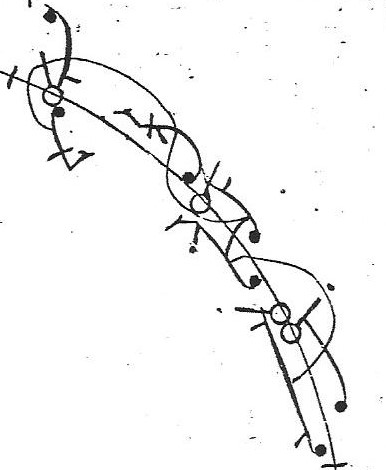

I will start with Orchesography and A Collection of Ball-Dances. Here are their lists of subscribers, to left and right respectively.

Among the Frenchmen, Cherrier, Debargues (usually called Desbarques) and Du Ruell were all stage dancers appearing regularly in London’s theatres during the early 1700s. Together with L’Abbé, Weaver singles out all three for praise in his Preface to Orchesography. The other ‘French’ names raise a series of questions. The first dancer we know called Camille to appear on the London stage was a ‘Young Mr. Camille’ at the Queen’s Theatre in 1712. The epithet suggests that he could, possibly, have been the son of an earlier dancer named Camille for whom we have no record of appearances in London. The dancer Cottin was billed at Drury Lane between 1700 and 1705, but there is no suggestion in the advertisements that he was ‘Monsieur’ Cottin. Monsieur Le Duc and Monsieur D’Elisle bear the same names as French dancers who had performed in the court masque Calisto in 1675. Did they stay in London to dance and to teach or are these other men? The Biographical Dictionary of Actors (full reference below) wrongly conflates Monsieur Le Sac with Queen Anne’s dancing master Mr Isaac. Le Sac was billed on the London stage in 1699-1700 and 1709-1710 and there was a musician of the same name working at Drury Lane during that period. Were the dancer and the musician one and the same? Finally, there is Monsieur Serancour, declared by the Biographical Dictionary of Actors to be the Davencourt who performed in a Grand Dance alongside L’Abbé and others at the Queen’s Theatre in December 1705. A quick look at the original advertisements in the Daily Courant reveals these to be the source of the confusion – ‘Davencourt’ in the first bill becomes ‘Serancour’ in subsequent ones.

The provincial dancing masters listed as subscribers in the two 1706 lists are not quite the same. They are scattered geographically in a way that suggests that Weaver’s appeal for subscribers was mainly concentrated on London. Norwich, Salisbury, Derby and York are represented in both lists, with the addition of Coventry in A Collection of Ball-Dances. Mr Delamain ‘of Dublin’ is joined there by Mr Smith in the Collection of Ball-Dances, while Mr Counly ‘Of Barbadoes’ in Orchesography becomes simply Mr Counly in the Collection. Without further research, we cannot tell why these differences appear, although they may well be simple omissions during typesetting.

This leaves us with the subscribers we are invited to assume are London dancers and dancing masters. Several names are well known from other contexts. There is Thomas Caverley, one of London’s leading teachers of ‘common Dancing’ (as Weaver calls it in the last chapter of his 1712 An Essay towards an History of Dancing) and one of Weaver’s close associates. Antony Caverley, who follows him in the lists, may have been Thomas’s son – unless he was his brother. ‘Mr. Essex’ is, of course, John Essex, who would go on to translate Feuillet’s 1706 Recüeil de contredances in 1710 as For the Furthur Improvement of Dancing. Weaver and Essex seem to have been friends. The Holts, represented in these lists by Walter ‘Senior’, Walter ‘Junior’ and Richard, belonged to a dynasty of dancing masters. I tried to disentangle them in an earlier blog post – Mr Holt and His Minuet and Jigg for Four Ladies. They seem to have been teachers of common dancing with no links to the stage. ‘Mr. Lally’ was perhaps the founder of a family of stage dancers. He was surely Edmund Lally (c1677-1760) whose son Edward was later to enjoy a short but promising stage career. I am not sure about the relationship between Edmund and the far more famous Michael Lally, they may have been father and son or uncle and nephew.

There are some other familiar names that I have passed over. John Groscourt (d. 1742) would be the dedicatee of John Essex’s translation of Pierre Rameau’s The Dancing-Master (1728), while ‘Mr. Gery’ (or Geary) was accorded a place in the preliminary pages to Weaver’s 1712 Essay, alongside Groscourt, Couch, Holt, Firbank and Lewis, as ‘happy Teachers of that Natural and Unaffected Manner which has been brought to so high a Perfection by Isaack and Caverly’. All, except for ‘Firbank’ (the musician and dancer Charles Fairbank), subscribed to both Orchesography and A Collection of Ball-Dances. Sharp-eyed readers will also have noticed an overlap between Weaver’s subscribers and the contributors to Edmund Pemberton’s An Essay for the Further Improvement of Dancing published in 1711. I will have more to say about that work in another post.

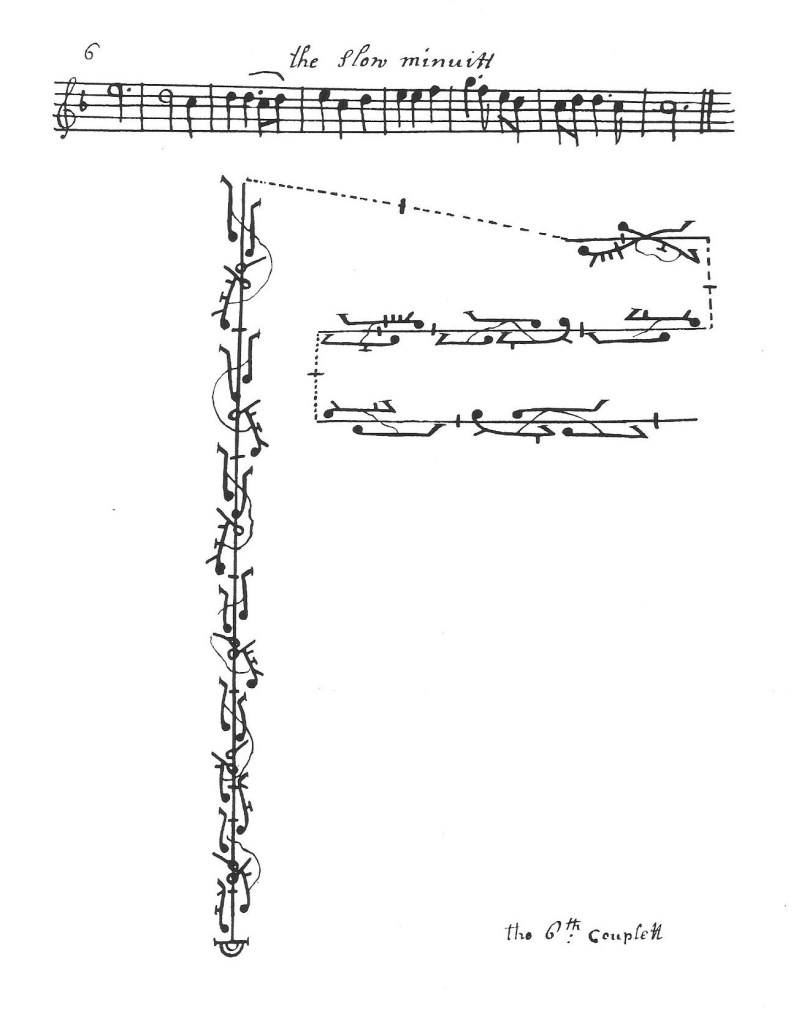

What about Weaver’s Anatomical and Mechanical Lectures upon Dancing, published some fifteen years later? Here is the list of subscribers, spread over a spacious two pages.

This list has only nine names in common with the earlier ones – Caverley, Couch, Essex (John), Holt (Walter), Lally (Edmund), Orlabeer, Pemberton (Edmund) and Shirley. The forenames come from the List of Subscribers and distinguish between members of the same family. William Essex, William Holt. Edward Lally and James Pemberton were all the sons of earlier subscribers. There are again a handful of provincial dancing masters, none of whom had subscribed earlier and, so far as I can tell, about eight men who were professional dancers in London’s theatres. They include William Essex (John’s son) and ‘Mr. Shaw’ who must surely be the much-admired English dancer John Shaw (d. 1725). Like the 1706 works, the majority of subscribers seem to have been dancing masters rather than dancers.

These subscription lists add to our knowledge of Britain’s (especially London’s) dancing masters, but they also call into question some aspects of our understanding of that world. Weaver’s criticisms of French dancers are well known, yet several were happy to subscribe to his English translation of a work they would surely have known in its French original. The appearance of several families of dancing masters should perhaps be no surprise, although their individual subscriptions suggest they had separate dancing schools. As I put this post together, I was struck by the amount of research still needed to uncover this network of dancers and dancing masters based in London and elsewhere. John Weaver’s Lists of Subscribers are certainly one place to start.

References:

Philip H. HIghfill Jr, Kalman A. Burnim and Edward A. Langhans, A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, … in London, 1660-1800. 16 Volumes. (Carbondale, 1973-1993)