An early dance friend recently suggested to me that the 19th-century waltz is more difficult than the 18th-century minuet and invited me to discuss the idea. So, here goes.

I have danced many minuets over the years and I am well acquainted with the challenges of the ballroom minuet, as described by Pierre Rameau in Le Maître a danser (1725) and Kellom Tomlinson in The Art of Dancing (1735). I am nowhere near as practised in the early waltz. My friend did not specify any particular version, so I will look at Thomas Wilson’s A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing (1816).

The minuet was the duet that opened 18th-century formal balls. It was danced one couple at a time before the scrutiny of all the other guests. It was, in effect, an exhibition ballroom dance. This did not mean that it was slow and stately, 18th-century minuets were lively and quite fast dances. It had specific steps and figures (floor patterns) that had to be performed in a set order. It also allowed for some improvisation, mainly through the use of ‘grace steps’ in place of the conventional vocabulary. Controlled and elegant deportment was essential, not least to enable the partners to manage and display their elaborate attire, including the gentleman’s hat.

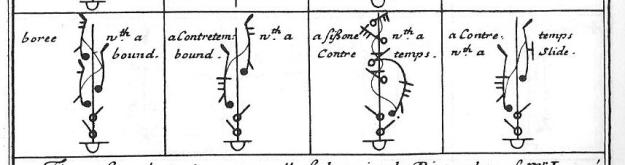

What was difficult about the minuet? Apart from the pressure of performance, both the steps and the figures were exacting. Minuet music is in 3 / 4 but the basic pas de menuet takes two bars of music, so four steps have to be fitted into six musical beats. There are two main timings, and both could be used within a ballroom minuet. The contretemps du menuet, the other basic step, had another different timing over six beats. All the steps of the minuet require a great deal of practice if they are to be performed with ease and elegance. There are five figures: the opening figure; the Z-figure; taking right hands; taking left hands; taking both hands, which is the closing figure of the dance. The Z-figure is the principal figure of the minuet. It can repeated at will and is often, but not always, reprised just before the final figure. Some idea of the steps and figures of the minuet is given by Kellom Tomlinson’s notation of the dance.

Kellom Tomlinson. The Art of Dancing (1735), Plate U

At balls, the minuet was addressed to the two highest ranking members of the audience, referred to as ‘the presence’. The dancers had to begin and end facing them and the figures had to be oriented in relation to them. The accurate performance of the figures, as well as their placing and orientation within the dancing space, needs a great deal of practice.

Musically the minuet was challenging. The couple could begin their dance at any point in the music (taking care to start on an odd-numbered bar), so their dance figures would inevitably cross the musical structure and phrasing at several points. Tomlinson tries to suggest such musical challenges in his notation of the minuet. This, too, needs much practice to master.

What about the waltz? How difficult was it? The waltz was always danced with a number of couples on the floor at any one time. It was a social dance and not meant as a display piece. Wilson distinguished between the French waltz and the German waltz. The French waltz began with the ‘Slow Waltz’, changed to the ‘Sauteuse Waltz’ and ended with the ‘Jetté, or Quick Sauteuse Waltz’. As the titles suggest, the dance got progressively faster. Each of these little waltzes had its own steps. In the slow waltz, these were a half-turn pirouette and a pas de bourée, over two bars of 3 / 4 music. The rhythmic pattern is reminiscent of the simplest timing of the basic pas de menuet. I can’t help feeling there was a link between them. The sauteuse waltz replaces the pirouette with a jetté-step combination and makes the first step of the pas de bourée a jetté. The jetté or quick sauteuse waltz had just one step, a jetté-hop combination, performed first on one foot and then on the other. Wilson’s explanations are not entirely clear and I am radically condensing them. It is obvious, though, that these steps need practice if they are to be well performed.

The German waltz was Wilson’s undoubted favourite.

‘The Construction of the Movements is truly elegant; and, when they are well performed, afford subject of much pleasing Amusement and Delight.’

This version of the waltz had two quite different, and slightly more complicated, steps than those in the French waltz. In all Wilson’s versions of the waltz, the dancers needed good deportment but – just as their dress was freer than in the 18th century – a degree of informality was acceptable.

There are no figures in the waltz, which simply follows a circular track around the dancing space with the partners turning as they go. The dance is not directed at those who may be watching. It simply tries to make best use of the available dancing space.

Thomas Wilson. A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing (1816), plate

One of the most complicated aspects of the early 19th-century waltz is the varieties of what would today be called ‘hold’. Wilson’s pretty frontispiece shows several of these.

Thomas Wilson. A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing (1816), frontispiece

The partners had to change hold as they dance. I suggest that this would have taken quite a bit of practice, certainly rather more than the basic steps. This is one area where the waltz is definitely more difficult than the minuet, in which the partners merely take hands from time to time.

Musically the waltz does not pose challenges. The dancers could start anywhere (although, like the minuet, on an odd bar) and they didn’t need to worry about musical structure or phrasing since the waltz is repetitious. However, they did need to worry about being in time with each other and fitting their steps and turns around each other. Again, this would have taken practice, just as it does with the modern waltz. There was also the speed of the dance, at least with the sauteuse and jetté or quick sauteuse waltzes, which made neat footwork a challenge. Giddiness with all the turning was perhaps seen as a pleasure rather than a difficulty.

So, which dance do I think was the most difficult? It has to be the minuet, for its status as an exhibition dance, the complexity of its steps and figures and the challenges of its musicality. The waltz has its fair share of challenges, but a simple early 19th-century waltz can be learned and enjoyed quite quickly. There is no such thing as a simple ballroom minuet.

![John Essex, For the Further Improvement of Dancing [1715?], plates 1 - 4](https://danceinhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/essex-1715.jpg?w=211&h=300)

![John Essex, The Princess's Passpied, [1715?], first plate](https://danceinhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/princess-passpied1.jpg?w=201&h=300)