Way back in 1999, I wrote an article which I hoped would settle once and for all the question of the identity of the dancer who first performed the role of Mars in John Weaver’s 1717 ballet The Loves of Mars and Venus. As he continues to be wrongly identified with the French dancer known as Louis ‘le grand’ Dupré, I thought I ought to include London’s Louis Dupré in my series about French male dancers in England, even though there is no certain evidence that he was French.

My 1999 article provides a detailed comparison of the dates on which the two Louis Duprés were dancing in London and Paris respectively, showing that they were indeed different dancers pursuing quite separate careers on each side of the Channel. I also included a brief summary of ‘le grand’ Dupré’s career – he still awaits a properly detailed biography – so in this post I will look only at the ‘London’ Dupré.

The other Louis Dupré was first billed in London at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 22 December 1714, as one of six dancers performing in the entr’actes. All of them may well have appeared on that theatre’s opening night on 18 December and then again on 20 and 21 December, when ‘Entertainments’ and ‘Singing and Dancing’ were advertised with no other details. John Rich had engaged six men and two women as dancers for his first season at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, because he saw dancing as an important draw for audiences while his new acting company gained the experience to challenge the established players at the rival Drury Lane Theatre. Dupré was undoubtedly Rich’s leading male dancer that season. He was billed for 71 performances in a repertoire that included a French Sailor duet with Mrs Schoolding, a Harlequin and Two Punches trio (with Moreau and Boval – Dupré was probably Harlequin) and a Grand Spanish Entry (with Moreau, Boval and the dancer Mrs Bullock). He was allowed a benefit performance on 7 April 1715, the second dancer’s benefit after Charles Delagarde who may have been the company’s dancing master.

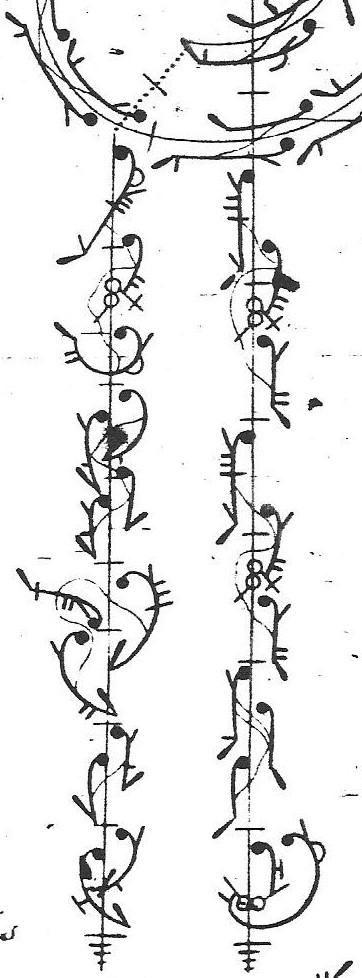

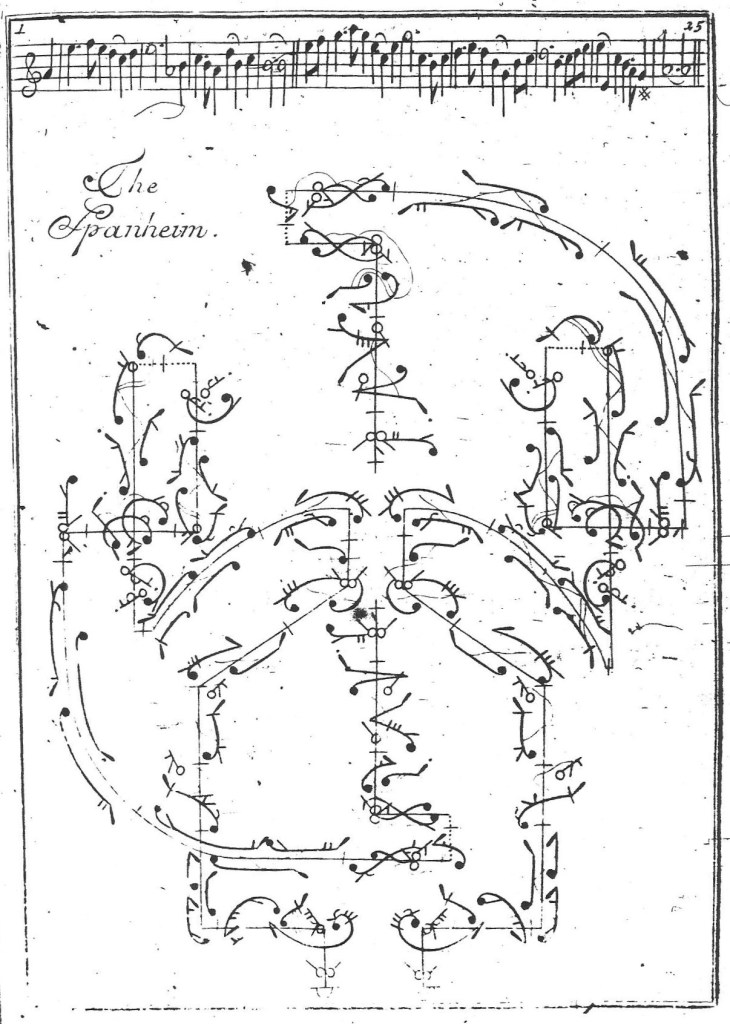

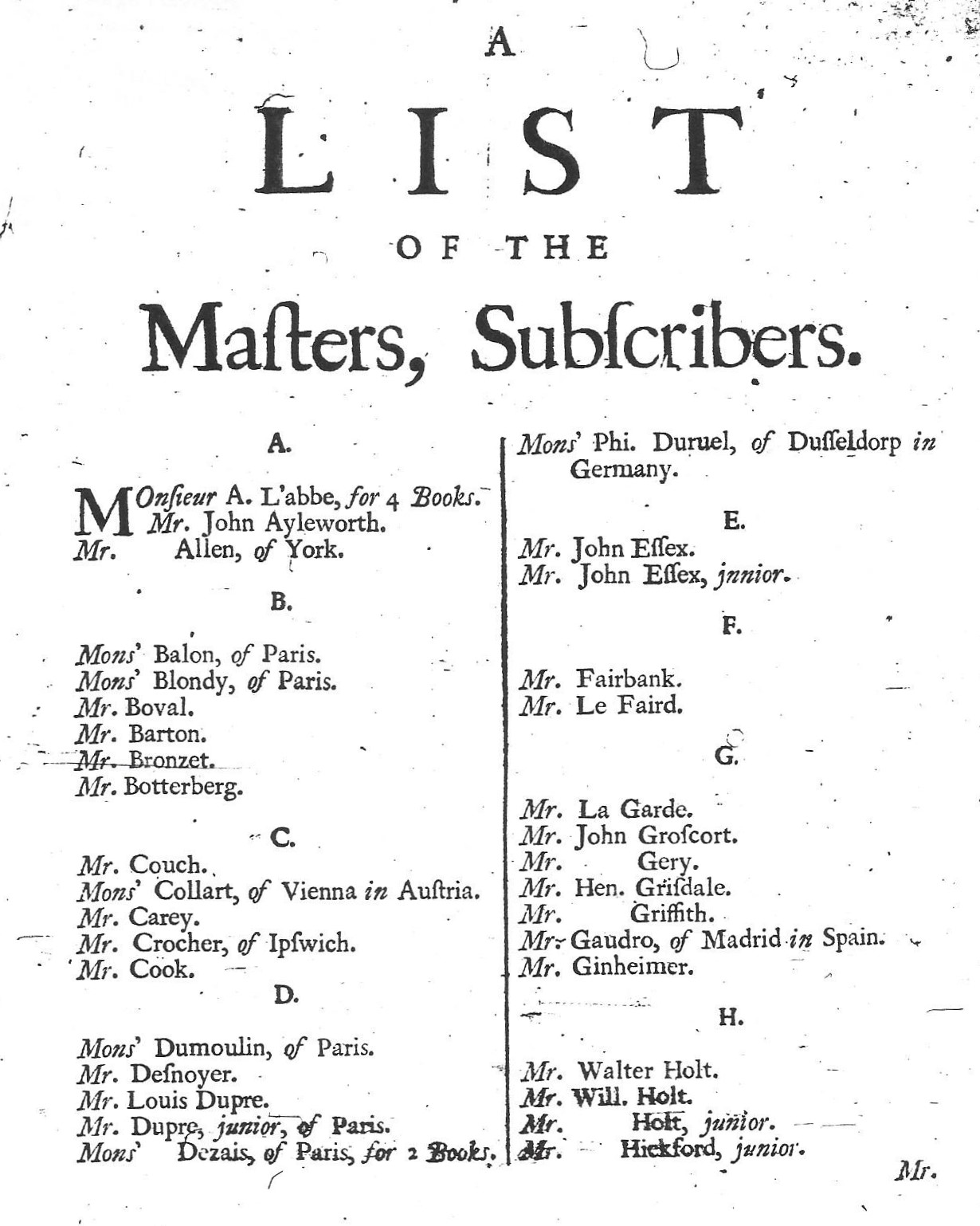

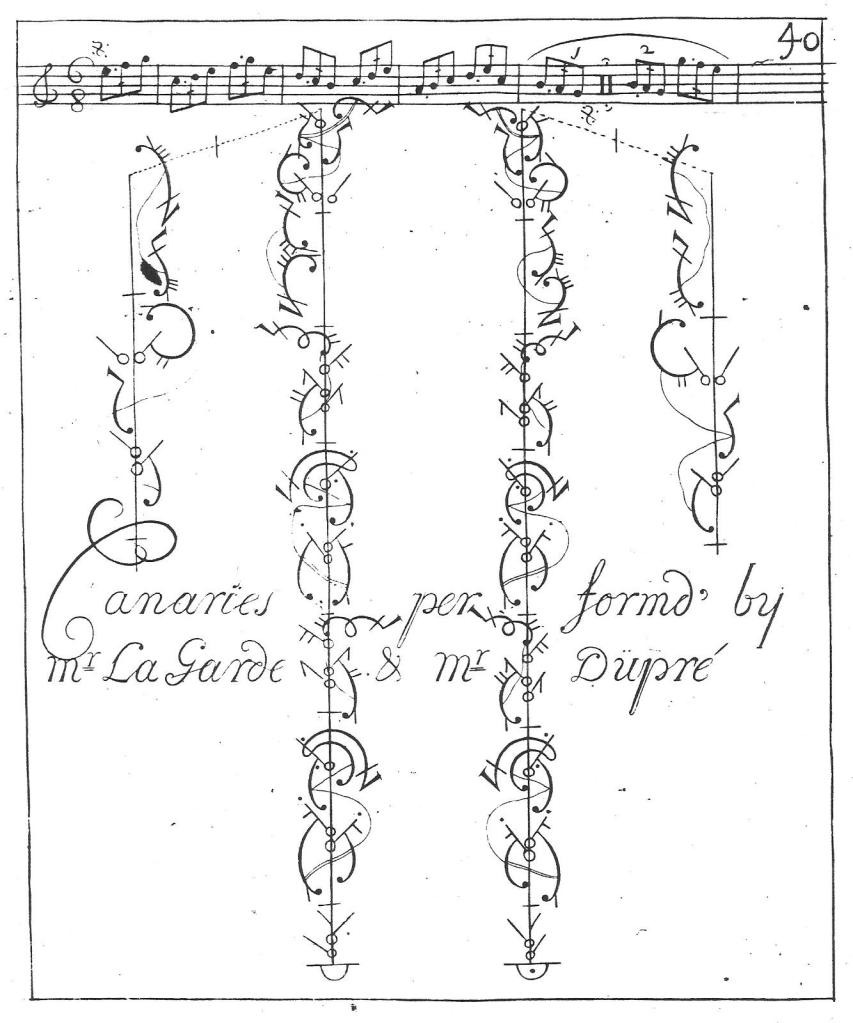

This may have been the season that Dupré danced a ‘Canaries’ with Charles Delagarde and the ‘Saraband of Issee’ and ‘Jigg’ with Ann Bullock. Both dances were choreographed by Anthony L’Abbé and published in notation within A New Collection of Dances in the mid-1720s. Dupré could have come to L’Abbé’s notice through Delagarde, whose career on the London stage had begun in 1705 and who had subsequently worked with L’Abbé. If all these men were indeed French (Charles Delagarde’s origins are also uncertain) and had professional links – perhaps through their dance training, their association is easy to understand.

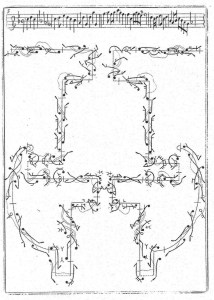

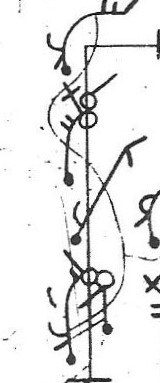

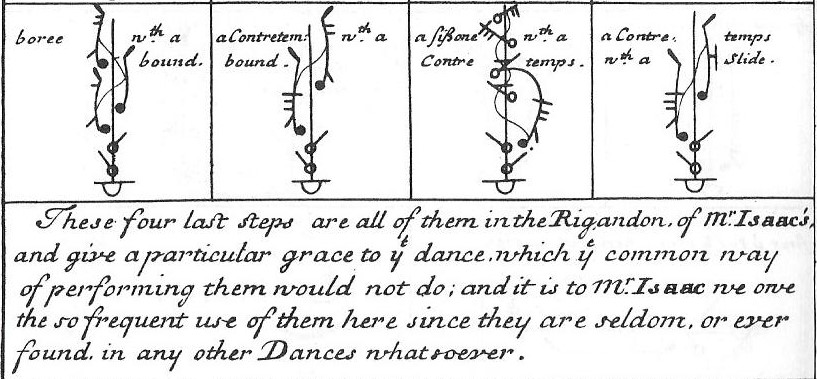

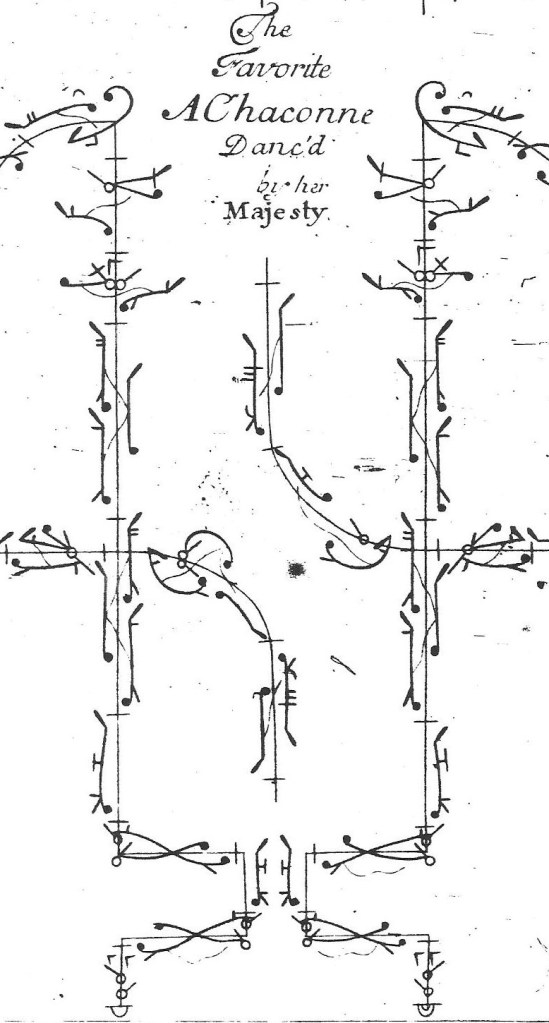

Charles Delagarde ‘who has not appeared these six years’ was billed at Lincoln’s Inn Fields from 1 January 1715 and 1714-1715 is the season in which he and Dupré were most likely to have danced together. L’Abbé’s ‘Canaries’ is to music from Lully’s 1677 opera Isis and is, as its title indicates, the dance type called a canary. The music is in 6/8 and has 48 bars in all. Here is the first plate.

Although it has its share of cabrioles and pas battus, as well as a passage with pas tortillés, on the page it is not a particularly demanding choreography for male dancers.

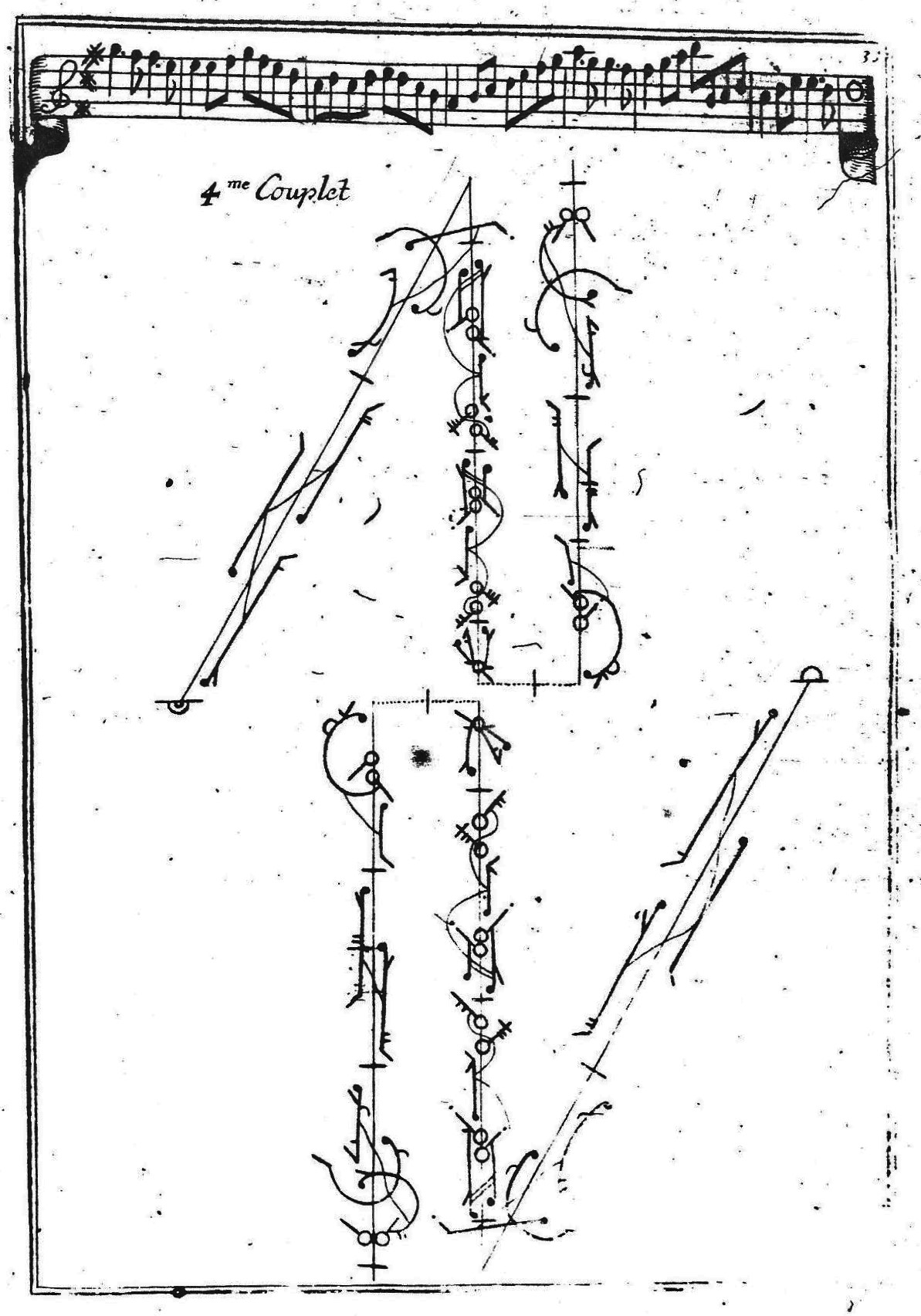

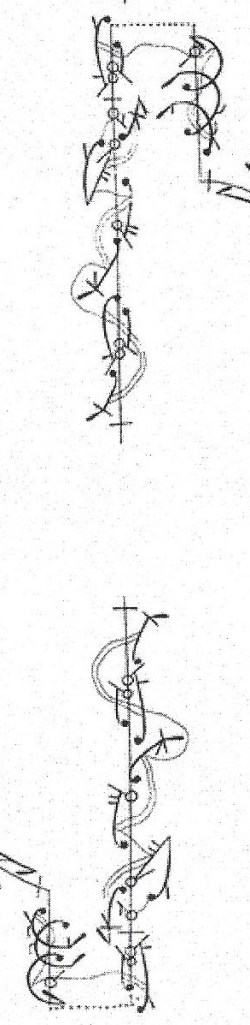

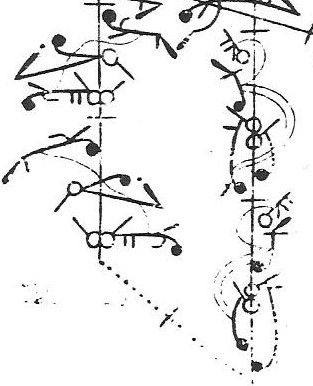

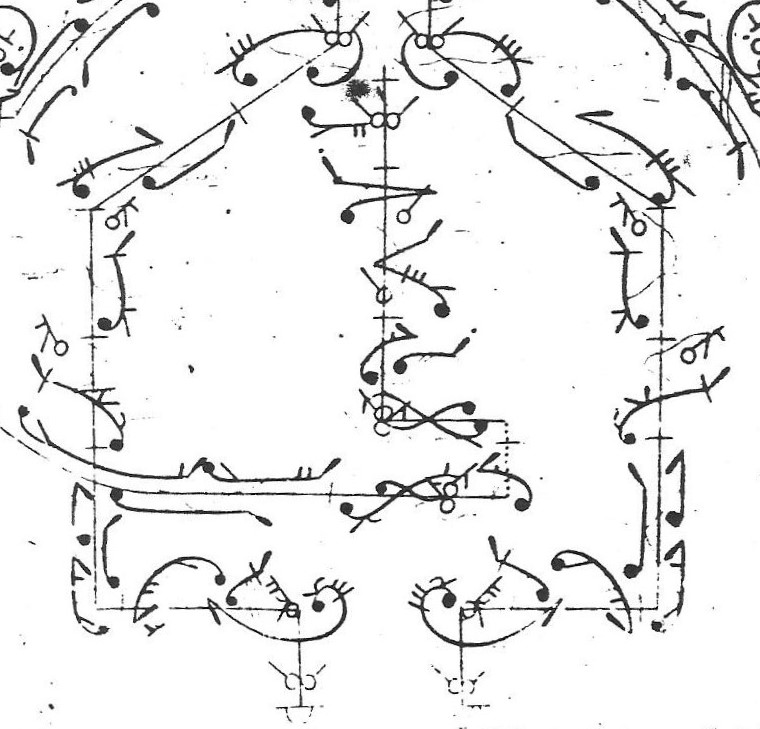

This was also the most likely season for Dupré to have danced with Mrs Bullock, a pupil of Delagarde who (as Miss Russell) began her dancing career in 1714-1715. L’Abbé’s ‘Saraband of Issee’, to music from Destouches’s 1697 opera Issé has Mrs Bullock matching Dupré with pas battus and pirouettes, although he gives her changements instead of Dupré’s entrechats-six. This dance has the time signature 3 and 64 bars of music. This is the first plate.

The ‘Jigg’ they danced together, either immediately following the ‘Saraband’ or quite separately, is to music from La Coste’s 1707 opera Bradamante and is in 6/4 with 48 bars of music. On the page, it has a straightforward vocabulary of steps.

I have glanced at these dances in earlier posts on Dance in History, but all are worth more detailed analysis.

Dupré moved to Drury Lane for the 1715-1716 season, his second on the London stage, perhaps because of the financial uncertainty surrounding John Rich and Lincoln’s Inn Fields. At Drury Lane, he immediately became the leading male dancer and partner to the dancer-actress Hester Santlow. They performed Spanish Entry and Harlequin duets together, as well as appearing as the lead couple in the popular entr’acte group dance Myrtillo. In 1716-1717, Dupré appeared with Hester Santlow and John Weaver in the latter’s The Loves of Mars and Venus. However, he seems not to have been happy at the Drury Lane Theatre, for he returned to Lincoln’s Inn Fields for the 1717-1718 season and would work for John Rich for the rest of his career.

Louis Dupré did not make his first appearance of the 1717-1718 season at Lincoln’s Inn Fields until 25 October 1717, when he was billed with ‘Mlle Gautier, from the opera at Paris, being the first time of her appearing upon the English Stage’. On 22 November, he took one of the title roles in a ‘New Dramatic Entertainment of dancing in Grotesque Characters’ entitled Mars and Venus; or, The Mouse Trap. He was Mars, with Mrs Schoolding as Venus and John Rich (under his stage name of Lun) as Vulcan. The afterpiece points to the possibility of past disagreements between Dupré and the Drury Lane management as well as Rich’s rivalry with John Weaver, and Dupré must surely have contributed his inside knowledge of Weaver’s ballet to the new entertainment.

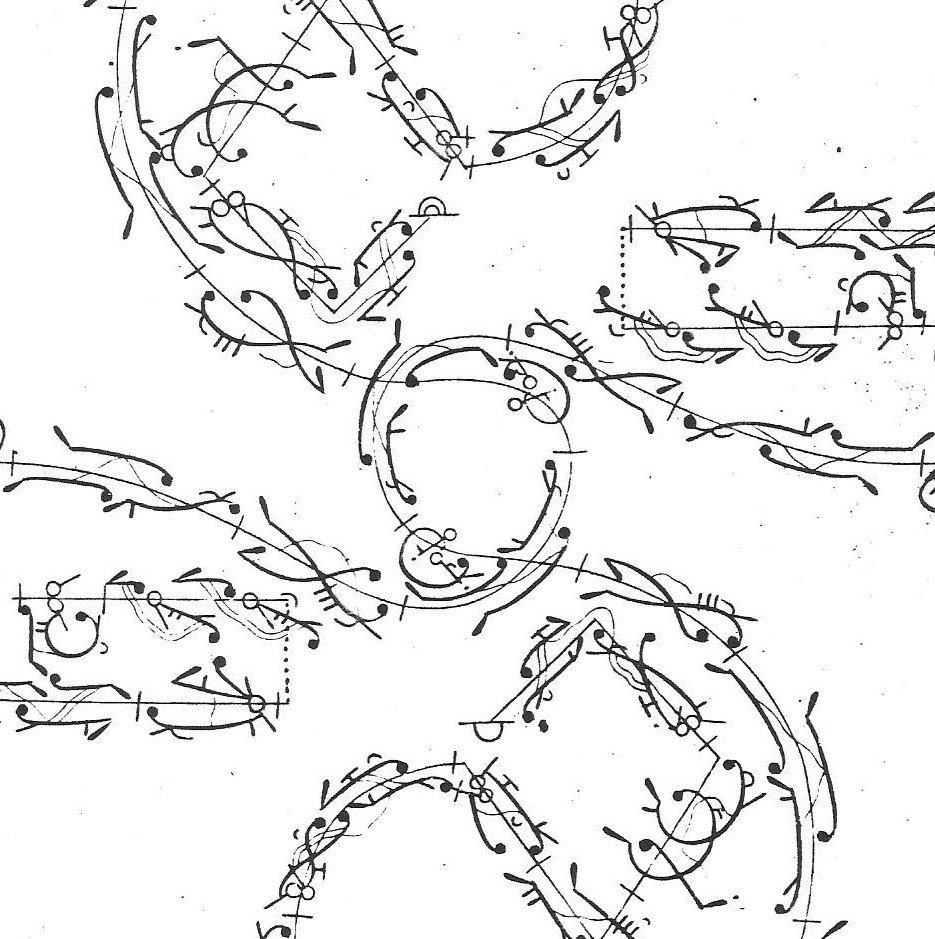

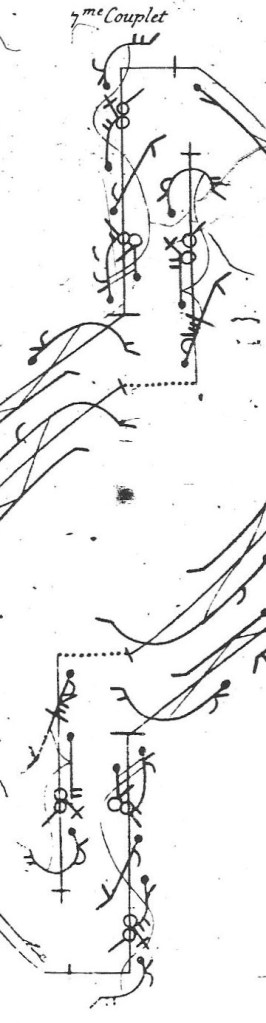

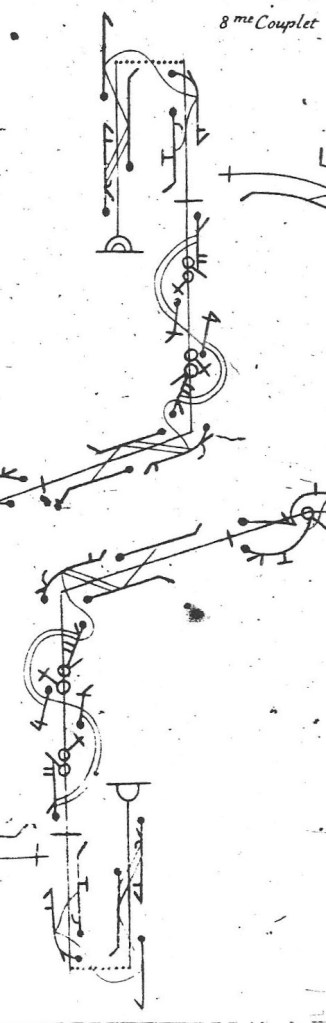

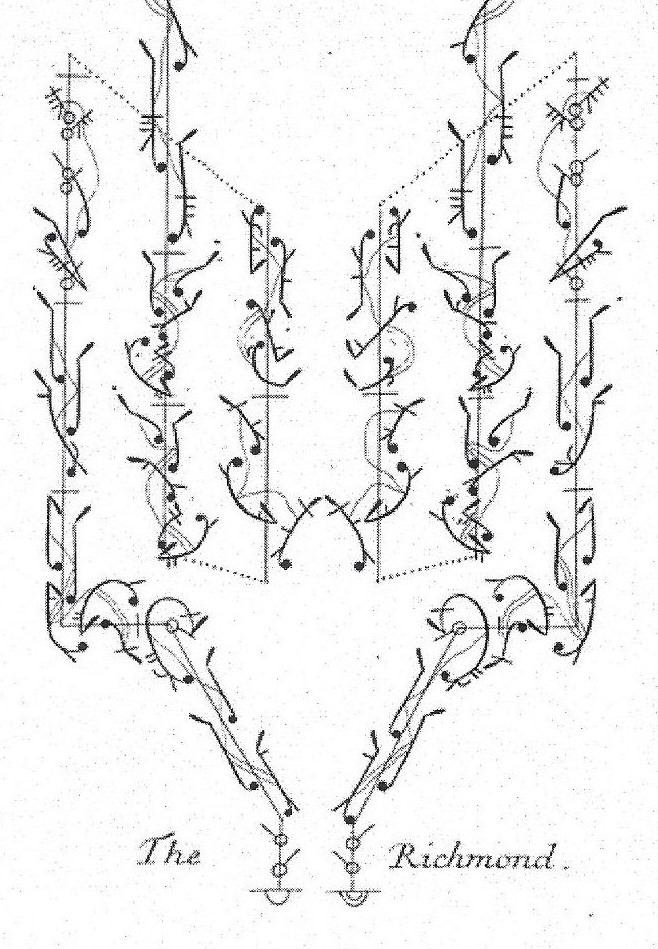

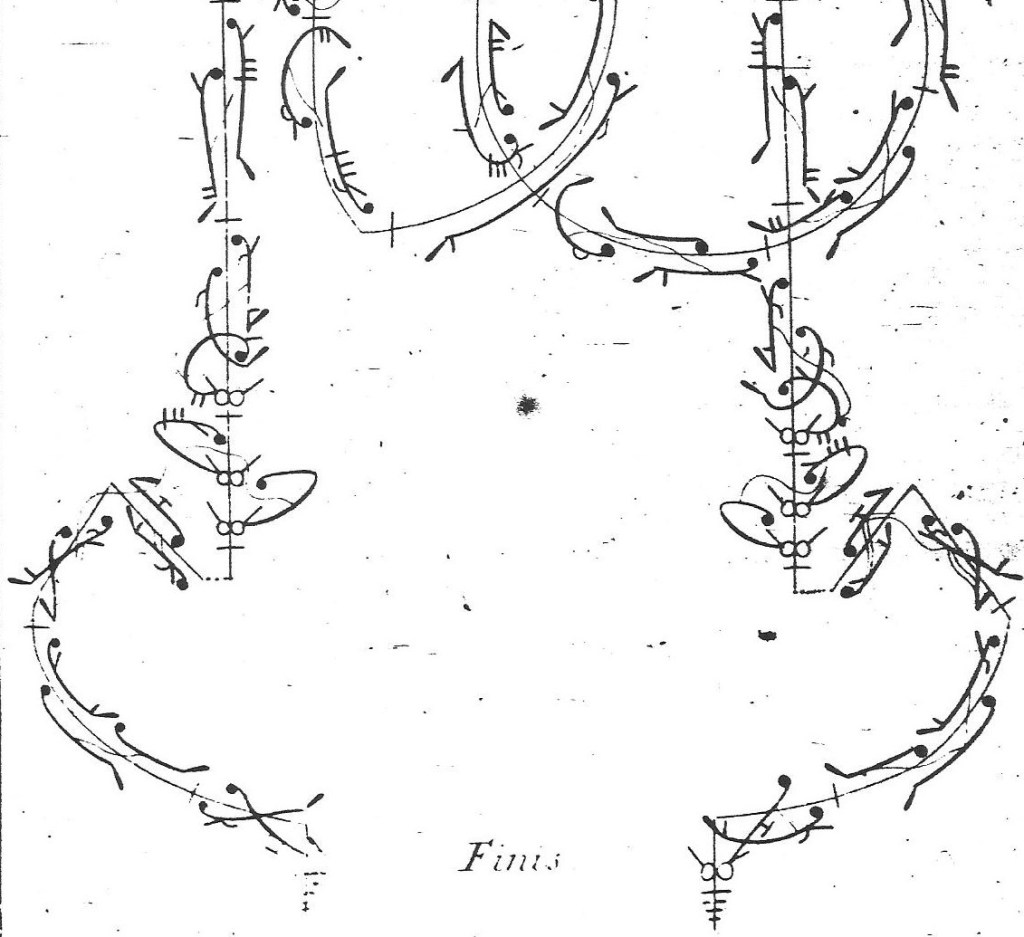

On 3 January 1718, another new afterpiece was advertised. The Professor of Folly was a ‘new Dramatick Entertainment of Vocal and Instrumental Musick after the Italian Manner, in Grotesque Characters’ for which Dupré had composed ‘all the Dances’ for himself and nine others (five men and four women), although it lasted for just a few performances. Then, on 24 January, Dupré appeared in the title role of Amadis; or, The Loves of Harlequin and Colombine with Mlle Gautier as Oriana and Lun (John Rich) with Mrs Schoolding as Harlequin and Colombine. This afterpiece was described as a ‘new Dramatick Opera in Dancing in Serious and Grotesque Characters’, although there were no singing roles. No scenario was published, but the characters in the serious part of the pantomime suggest a link with Lully’s 1684 opera Amadis and this is reinforced by Anthony L’Abbé’s solo for Dupré of around the same date to the chaconne from the opera. Here is the first plate of the notation from L’Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances.

I have elsewhere suggested that this solo was performed within the pantomime. It is certainly one of the most demanding of the male solos recorded in notation, and also seems to be one of the least known and least reconstructed by modern practitioners of baroque dance. It has 92 bars of music and its technical challenges include three entrechats-six in a single bar of music (1st plate) , a pirouette with two-and-a-half turns in a single bar (3rd plate) and a pirouette with four turns over three bars of music (6th and final plate). Again, I have looked briefly at this solo in earlier Dance in History posts, but it calls for both technical analysis and detailed comparison with other notated male solos.

During the late 1720s, Dupré danced in all of Rich’s most important pantomimes. In 1724-1725 he was billed as the first of three Furies in Harlequin a Sorcerer: With the Loves of Pluto and Proserpine (21 January 1725). In Apollo and Daphne; or, The Burgomaster Trick’d (14 January 1726) he danced as a Spaniard in the pantomime’s concluding divertissement, initially with Mrs Bullock as a Spanish Woman and later partnered by a succession of the company’s leading female dancers. This afterpiece marked the return to London of Francis and Marie Sallé, now young adults, who danced the title roles. These evidently required the expressive mime in which they excelled (a skill which Dupré may have lacked). In The Rape of Proserpine; or, The Birth and Adventures of Harlequin (13 February 1727), Dupré was one of three Gods of the Woods, one of five Demons and, in the final divertissement, the element Earth (with Mrs Pelling as his partner ‘Female’). This was another pantomime in which Francis and Marie Sallé were the leading dancers (although the title role and other roles in the serious part were performed by singers). In The Rape of Proserpine, Dupré was no longer billed first among the male supporting dancers. The last pantomime in which he danced was Perseus and Andromeda; or, The Cheats of Harlequin (or, The Flying Lovers) (2 January 1730). He was one of seven Infernals, but again he had lost his primacy among the men. However, in all these pantomimes Dupré danced serious roles which may well have required virtuosity, and he kept them until the end of his career.

His repertoire of entr’acte dances was also predominantly serious. As in the first years of his career in London, it included several ‘Spanish’ dances, either duets or for a group, as well as Chaconnes, which were mostly duets. He was never billed solo as Harlequin, although the trios and duets which he performed may well have had solo passages. Dupré’s last new entr’acte dance, first performed on 14 January 1734 at Covent Garden, was Pigmalion. This was Marie Sallé’s ballet, with Malter in the title role and Sallé herself as the statue Galatea. Dupré was billed as the first of six supporting male dancers, described in a review in the Mercure de France for April 1734 as Sculptors who performed a ‘danse caracterisée, le Maillet et le Ciseau à la main’. It seems that, at the end of his career when he must have been in his forties, Dupré was still capable of virtuosic dancing.

Dupré’s last recorded performance was at Covent Garden on 22 May 1734. That season, he had been billed for 34 performances in the entr’actes (the only dance named in the advertisements which featured him was Pigmalion) and 55 performances in three pantomimes (The Necromancer, Apollo and Daphne, and Perseus and Andromeda). If he was the ‘Lewis Dupre from the parish of St Anne Westminster’ who was buried at St James Paddington on 5 August 1734, then it seems he died suddenly. There was apparently no mention of his death in the newspapers, but he did not return to the stage in 1734-1735. The Dupré billed at Covent Garden that season danced a different repertoire and was probably the ‘Dupré Junior’ of earlier seasons. Louis Dupré’s death in 1734 or 1735 is confirmed by the acceptance of the ‘Widow Dupré’s tickets’ at Covent Garden on 2 December 1735. She continued to receive such benefit performances until at least 1740, underlining both Rich’s generosity to his players and Dupré’s value to him as a dancer in his company over nearly twenty years.

Louis Dupré’s career reveals both the opportunities and the difficulties faced by male professional dancers in London’s theatres during the early 18th century. His technical skills were exploited by John Rich, who needed dancers to draw audiences following the opening of Lincoln’s Inn Fields in December 1714. Dupré also faced competition from other dancers – like Francis Nivelon, who had exceptional abilities as a comic dancer, and Francis Sallé, who was probably no less virtuosic and of a younger generation. Both overtook Dupré in the ranks of dancers at Lincoln’s Inn Fields and then Covent Garden (and both will feature in my series on French male dancers working in London). Sadly, like most dancers, male and female, performing in London during the early 1700s, we have no portrait of the other Louis Dupré.

Further Reading:

Moira Goff, ‘The “London” Dupré’, Historical Dance, 3.6 (1999), 23-26

Linda Tomko, ‘Harlequin Choreographies: Repetition, Difference, and Representation’ in “The Stage’s Glory” John Rich, 1692-1761, ed. Berta Joncus and Jeremy Barlow (Newark, 2011), 99-137.