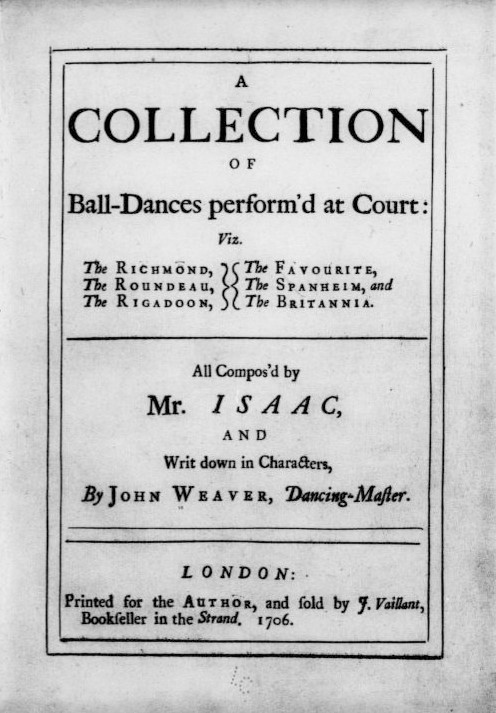

In my previous post, I looked at the opening and closing sections in each of Mr Isaac’s six dances published in 1706. Here, I turn my attention to some of his choreographic motifs and his versions of some of the basic steps of baroque dance.

Choreographic Motifs: The Right Line

As I work on each of these six dances (a project which is still in progress), I am taking note of one of Isaac’s choreographic motifs in particular. In all of the six dances, except for The Rigadoon, there is at least one sequence danced on a right line. In Orchesography, Weaver describes a ‘Right Line’ as ‘that which extends itself in Length, from one end of the Room to the other’ and illustrates it as running from the presence to the far end of the room in the centre of the dancing space. He is, of course, simply translating what Feuillet says (and illustrates) as his ‘ligne droite’. The feature which makes Isaac’s motif surprising is that the couple face one another and dance along this ‘Right Line’, so one of them has their back to the presence and screens the other from view. (I am assuming, perhaps wrongly, that the presence is on the same level as the dancers and not above them).

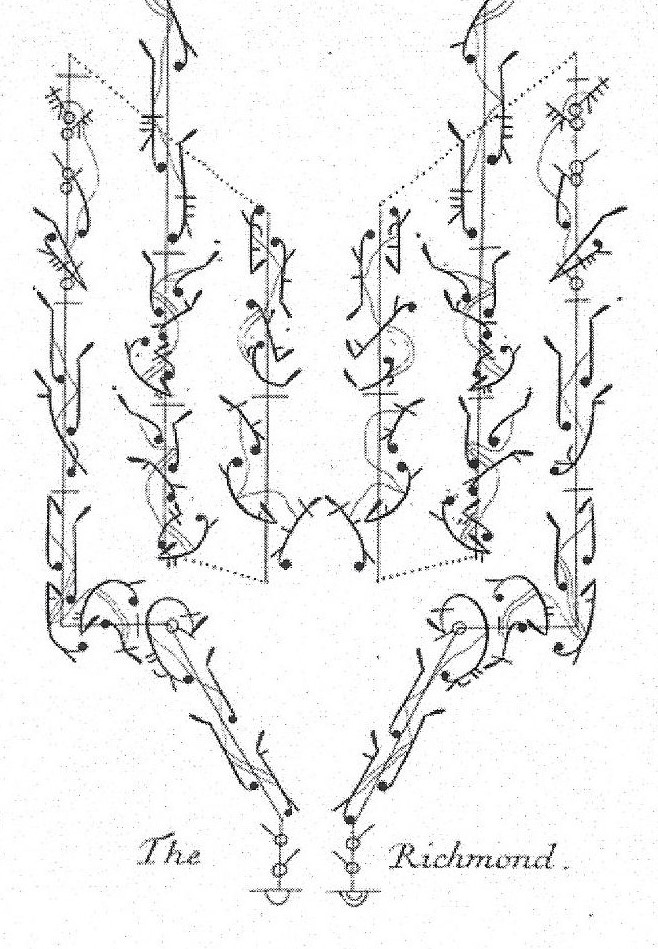

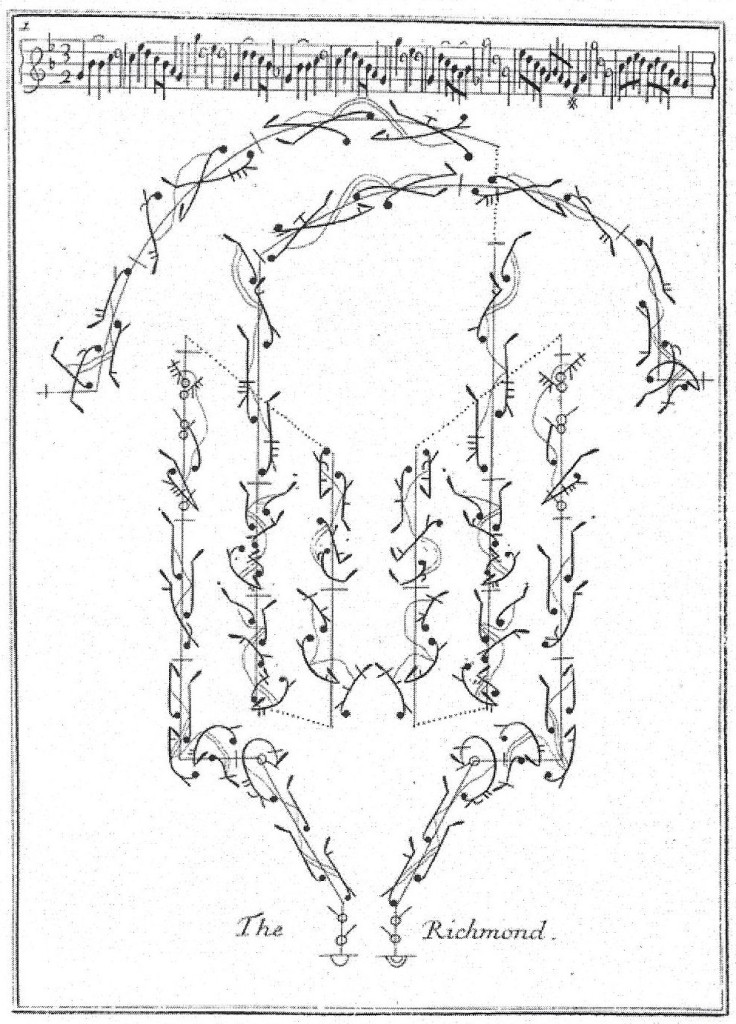

The Richmond

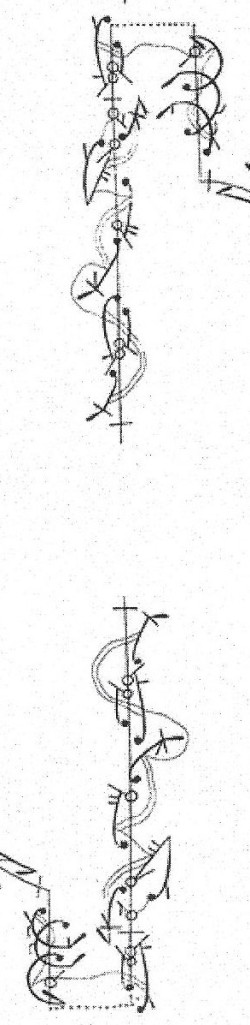

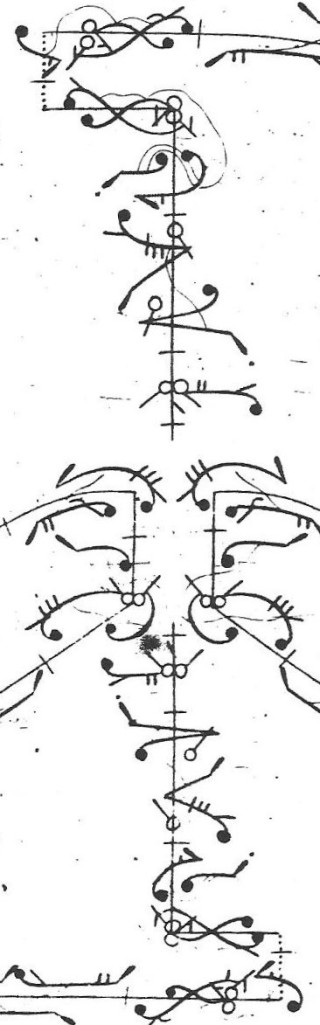

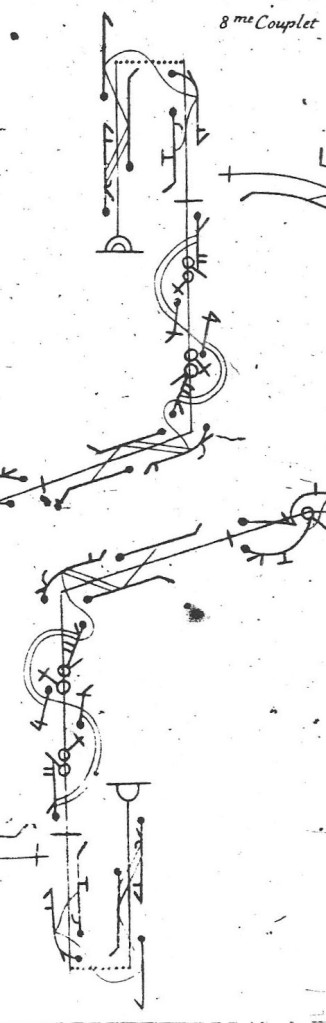

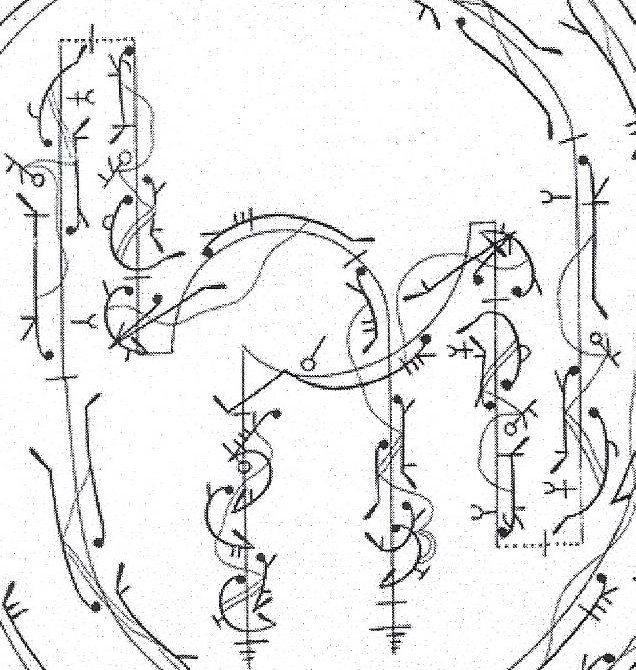

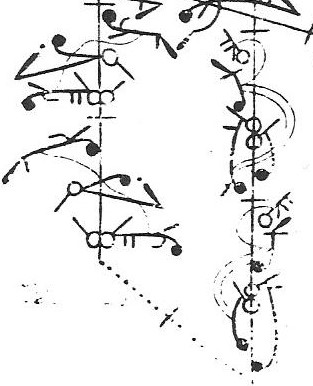

The Richmond has one sequence on a right line, roughly half way through the choreography, which begins on plate 3 and finishes on plate 4.

With the woman backing the presence, they approach one another and then retreat. Each then travels to the right for another sequence in which they move towards one another again on a right line, although they are now offset so both dancers can be seen from the front. The sequence of steps is complex, in keeping with this English hornpipe.

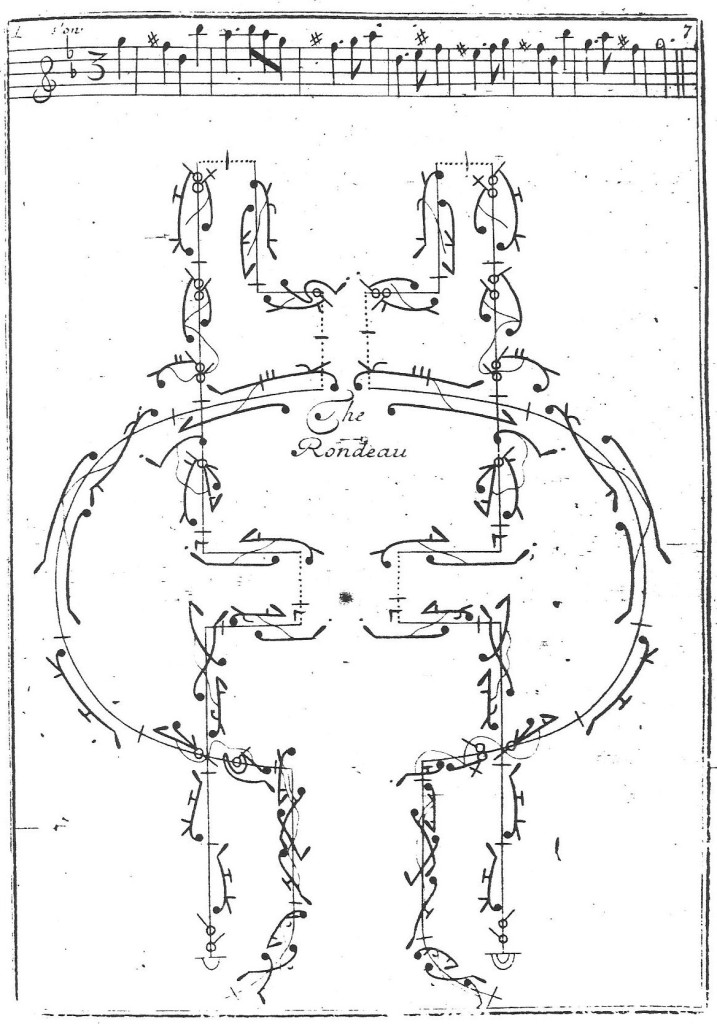

The Rondeau

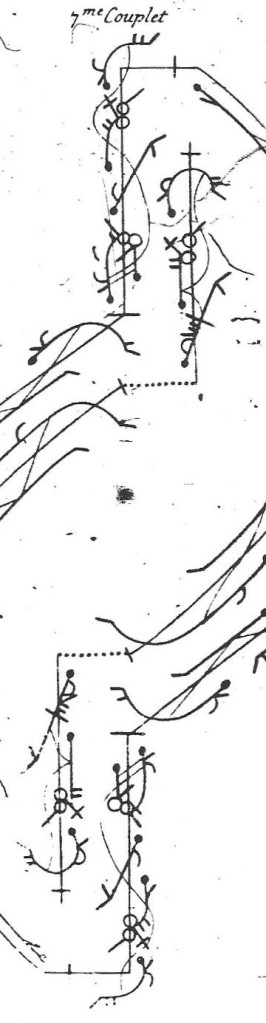

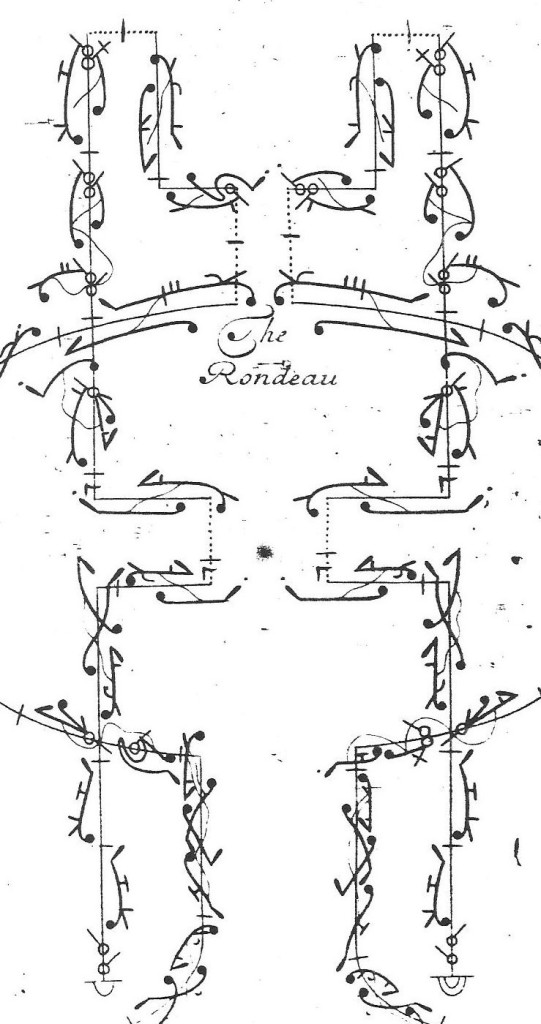

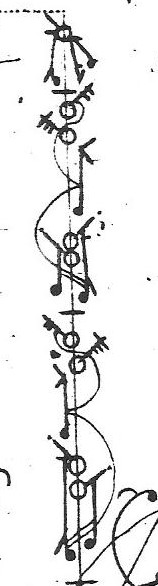

The Rondeau also has a single sequence on a right line, this time around halfway through the minuet section with which the dance ends.

The man has his back to the presence. The pair approach one another and then retreat to begin a circular line (on the next plate) which will bring them face to face again, this time on a diametrical line.

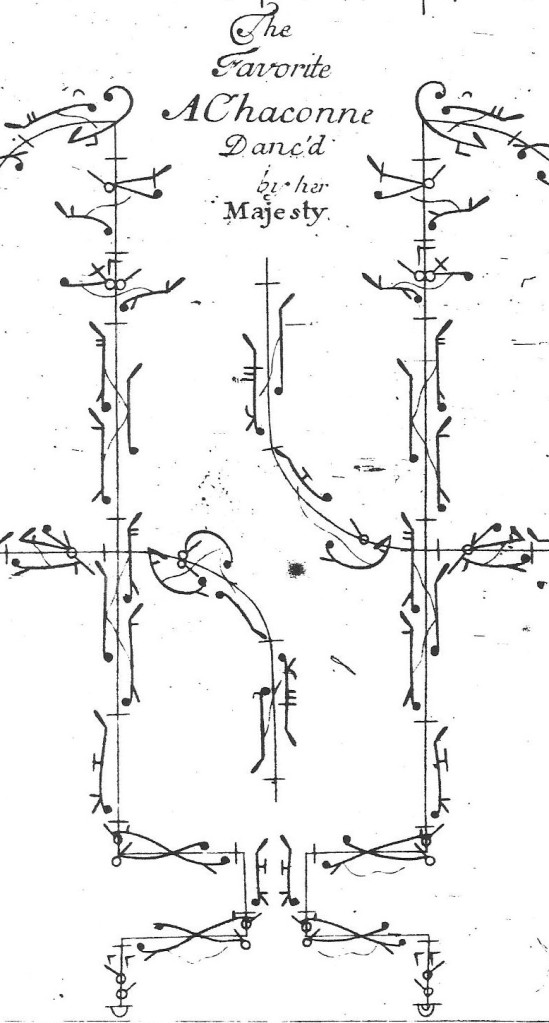

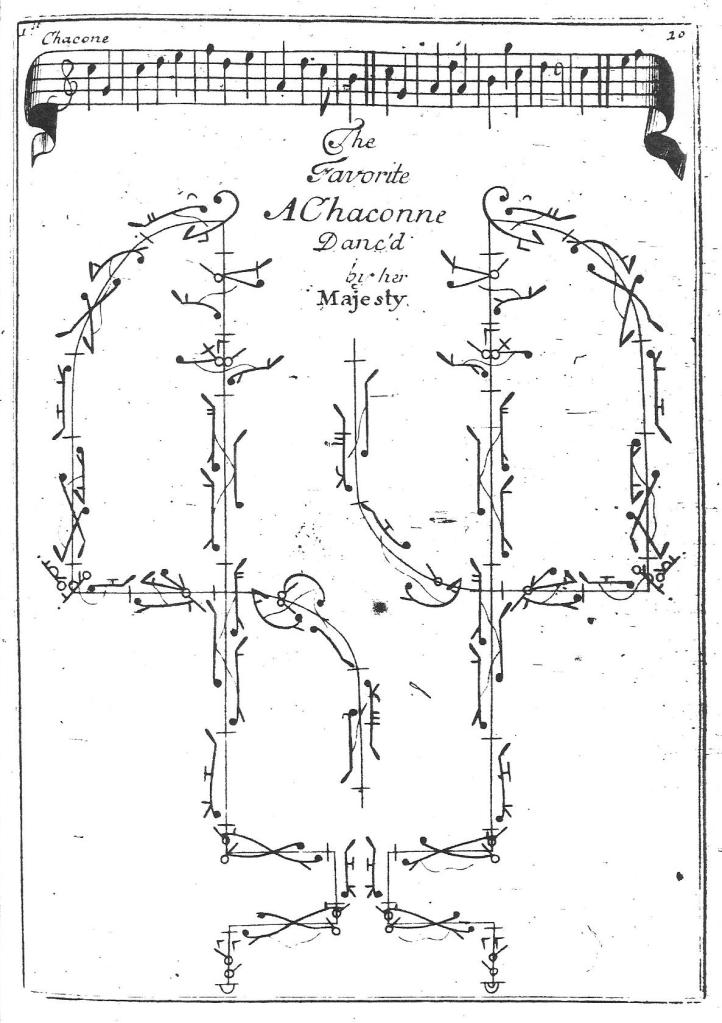

The Favorite

The Favorite has two sequences on a right line. The first occurs in the chaconne with the lady backing the presence (plate 2). The second is in the first part of the bourrée with the man backing the presence (plate 5)

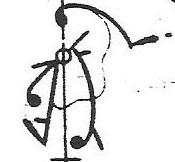

This was the dance that drew my attention to the motif, simply because in the chaconne the woman performs a coupé battu to the presence before she turns her back to face her partner (at the top of the detail from plate 2) and this includes a plié on the pas battu which makes it seem like a courtesy. (The man does the same step facing upstage). This figure is followed by another on a diametrical line. The second of these motifs, in the bourrée, has the man with his back to the presence and brings the two dancers together to take right hands for a circular figure.

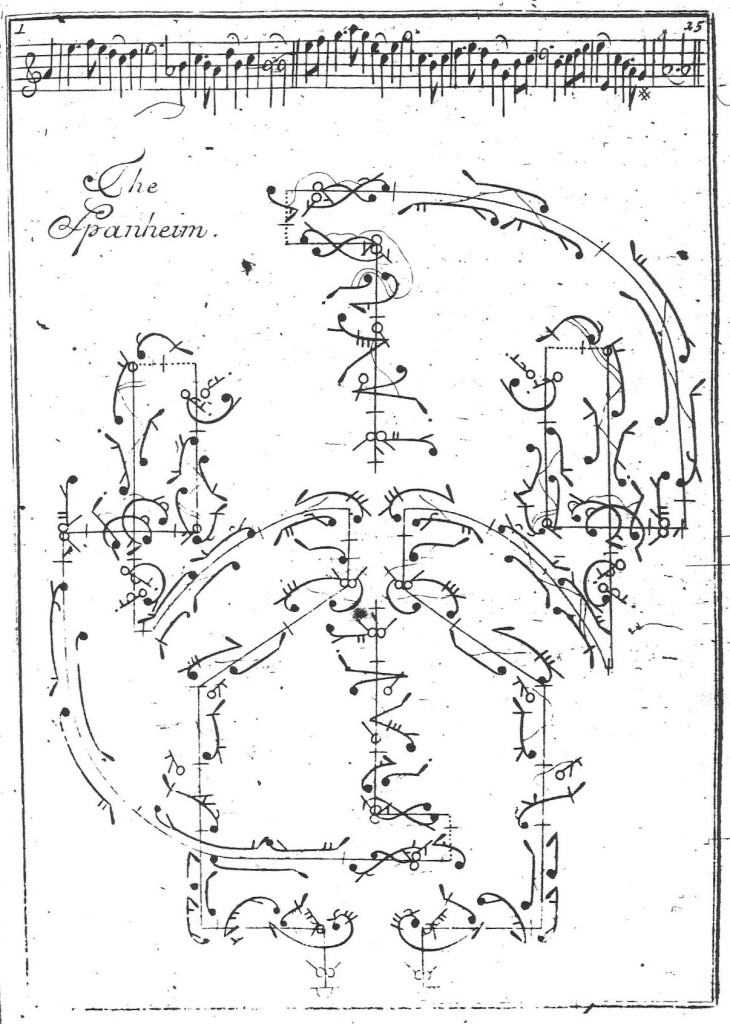

The Spanheim

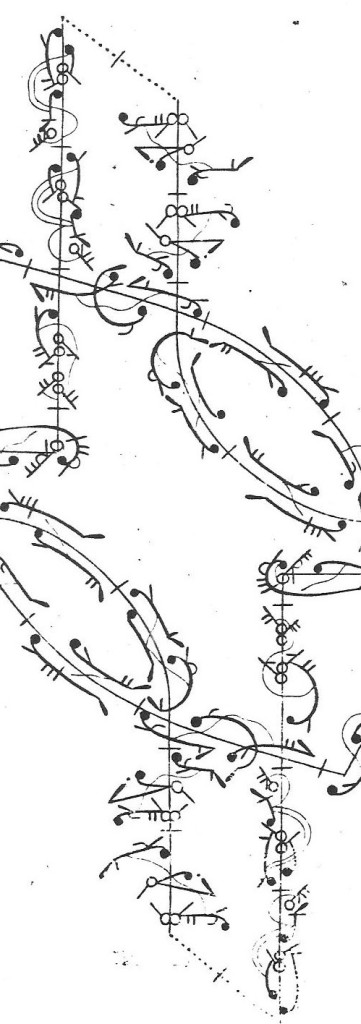

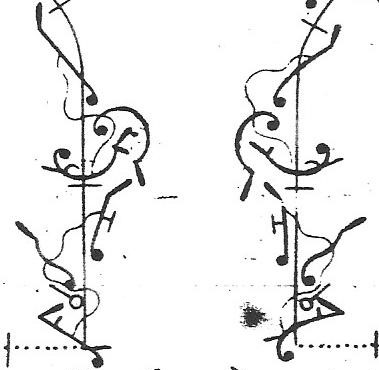

The Spanheim also has two figures on a right line. The first comes about a quarter of the way through the dance and the second just over half-way, within the full repeat of the music.

The first of these figures takes only three bars, while the second lasts for five bars. The first time, the woman has her back to the presence and the second time she faces it. The notation for the second right line shows the dancers as slightly offset, although their preceding steps and figure indicate that they are indeed face to face.

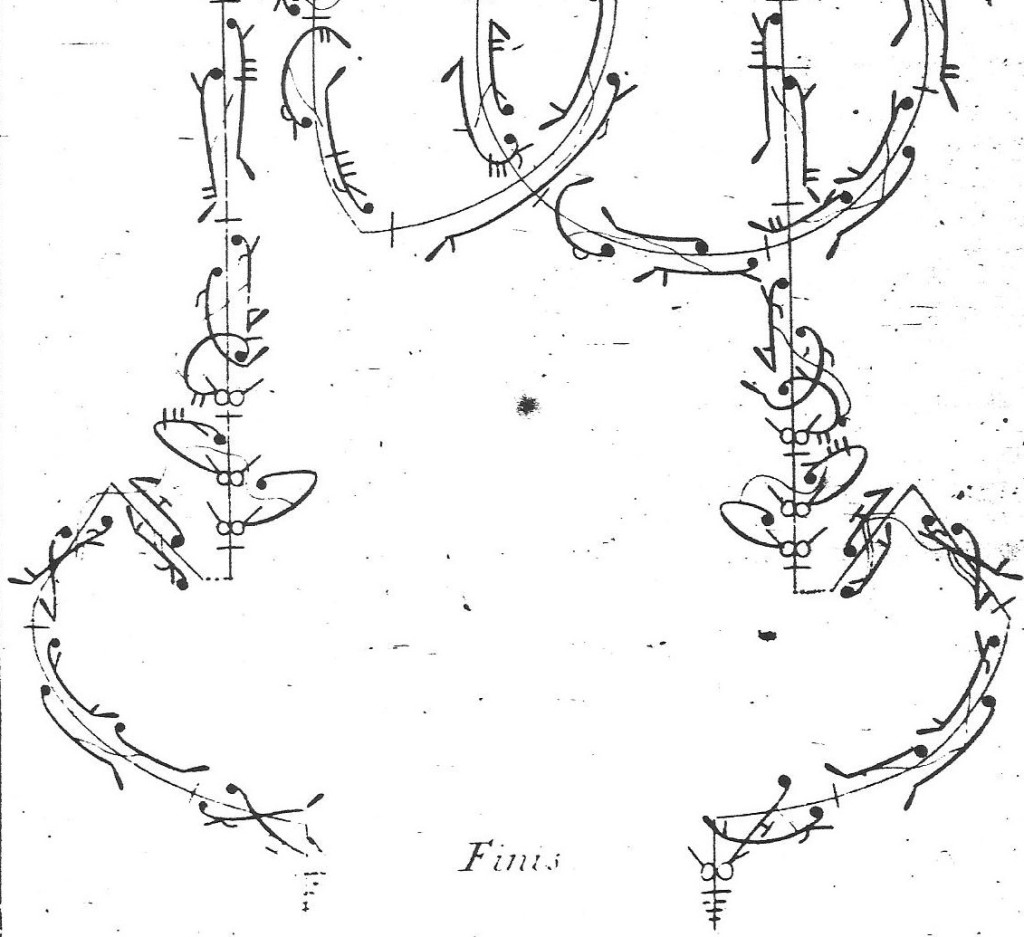

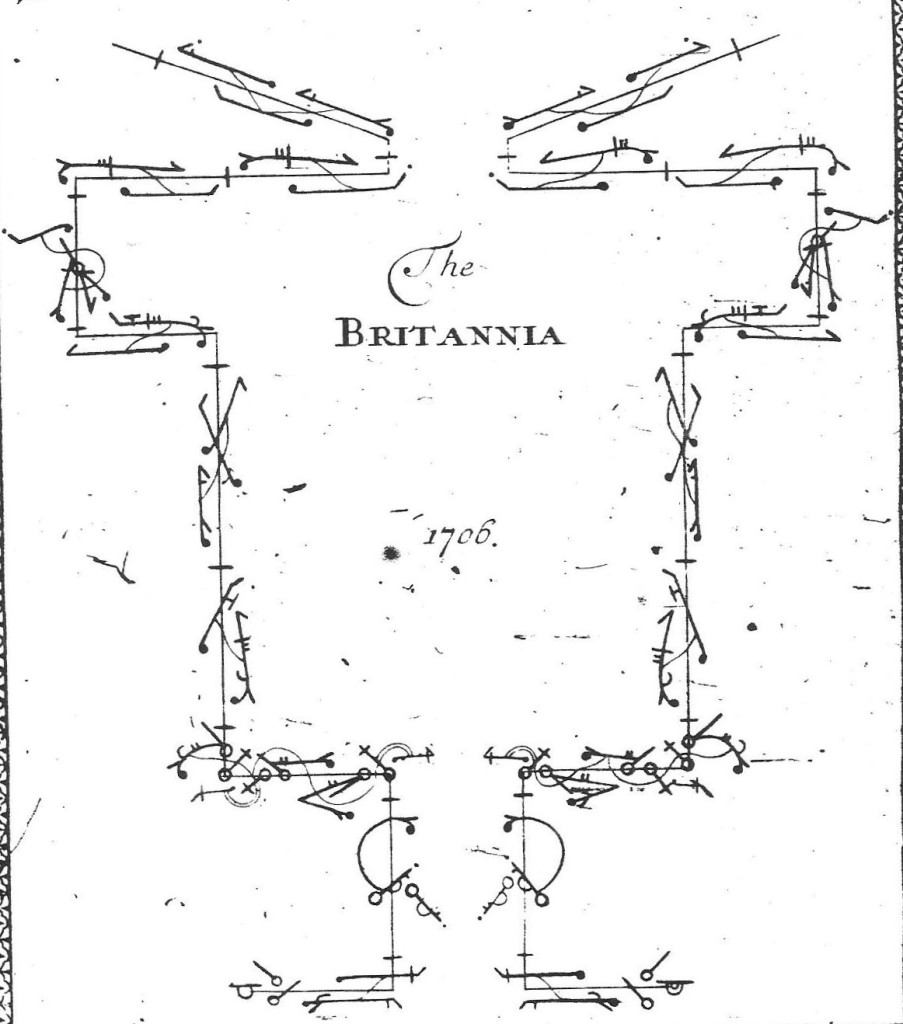

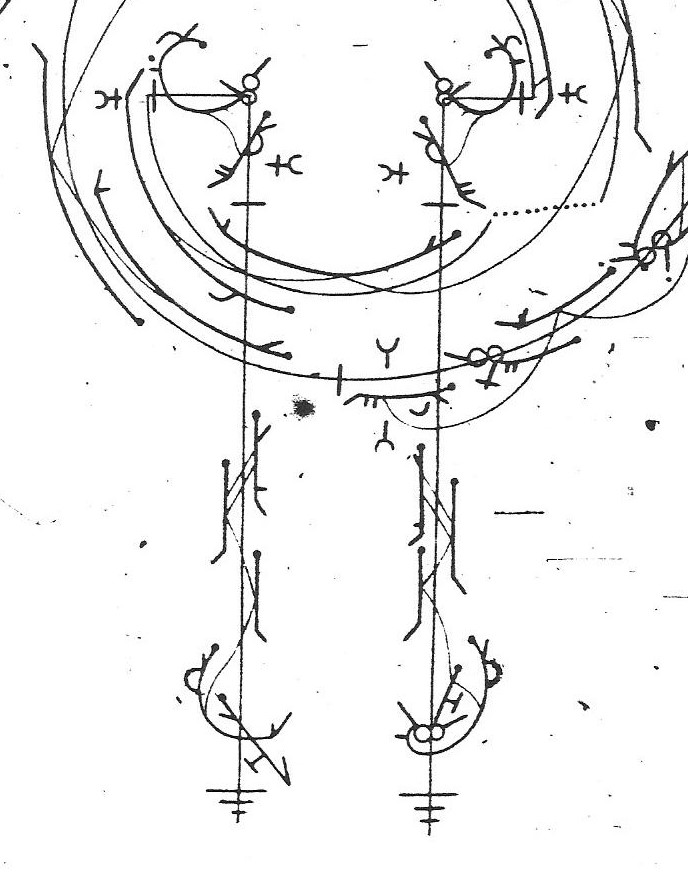

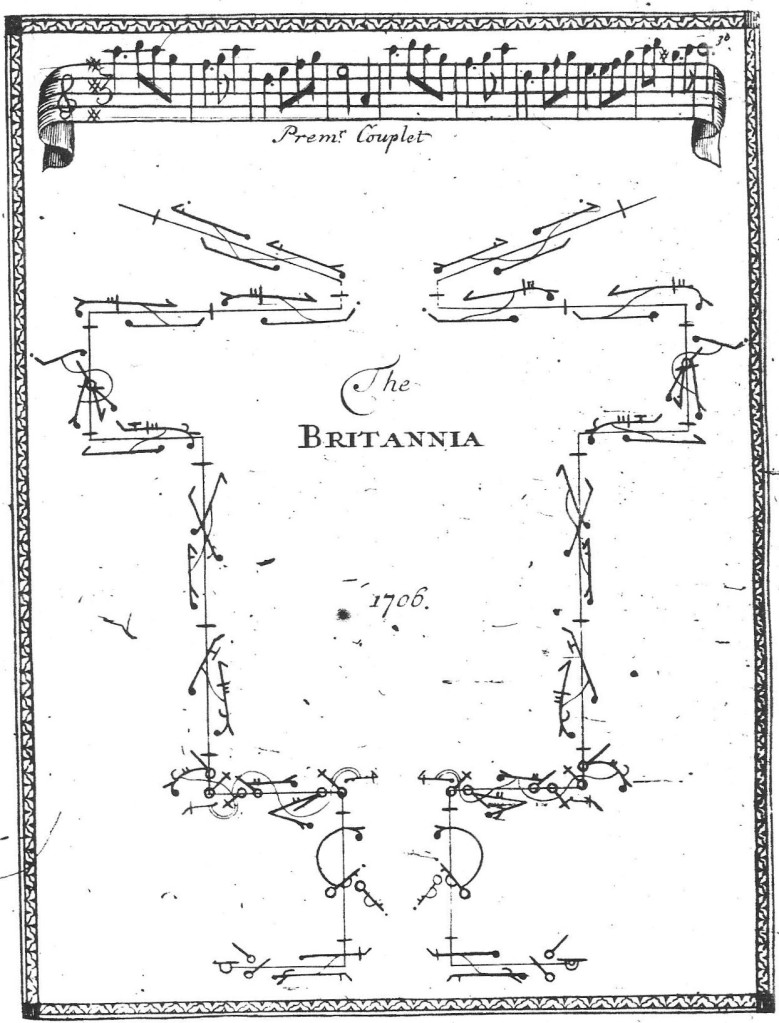

The Britannia

The last of the six dances, The Britannia, has three sequences on a right line. The first comes within the first half of the bourrée, with the woman backing the presence, and has the couple approaching one another, turning their backs and turning to face each other again.

The second and third right line figures are within the early sections of the minuet. Both are fleeting and the dancers face the sides of the dancing space (or even the presence and end of the room) as much as each other. In the second, the man is closest to the presence and in the third it is the woman.

There is even the hint of yet another figure on a right line, in the form of a single step just a little further on in the minuet, with the man closest to the presence.

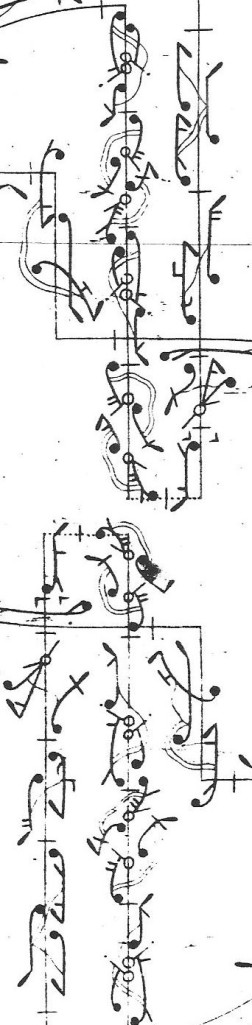

Isaac reveals some preferences in his choice of steps for these right line figures. He uses paired jettés-chassés in The Richmond, The Rondeau and The Britannia, and he also turns to pas de bourrée incorporating an emboîté and a plié. Similarly, he likes to use a coupé with an emboîté and an ouverture de jambe leading to a pas sauté – either a jetté, a jetté-chassé or a sissonne (the vertical jump from two feet to one that completes the pas de sissonne).

Isaac’s Steps

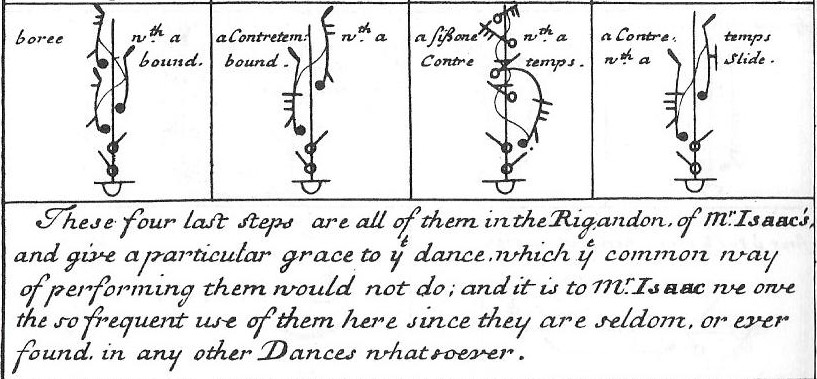

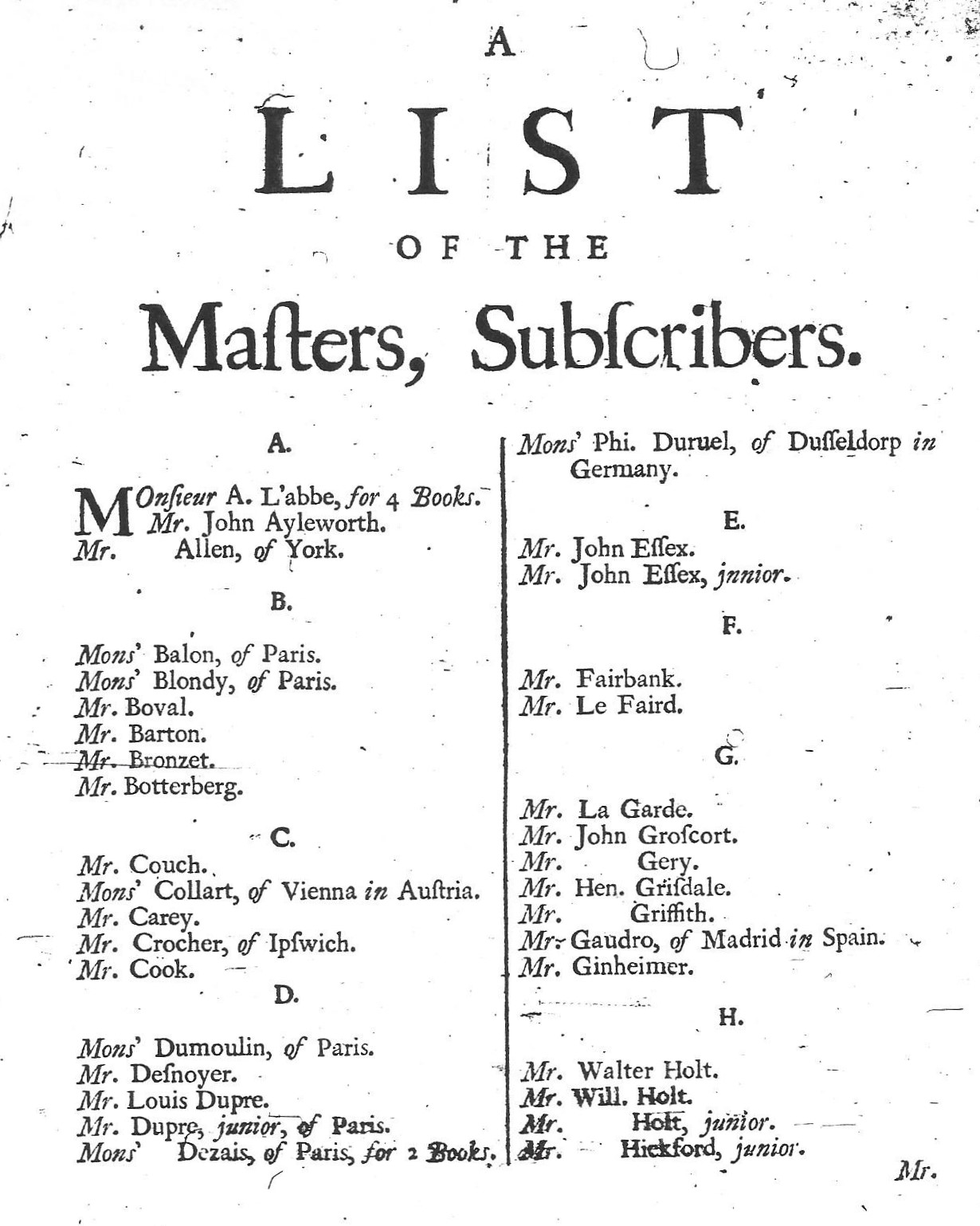

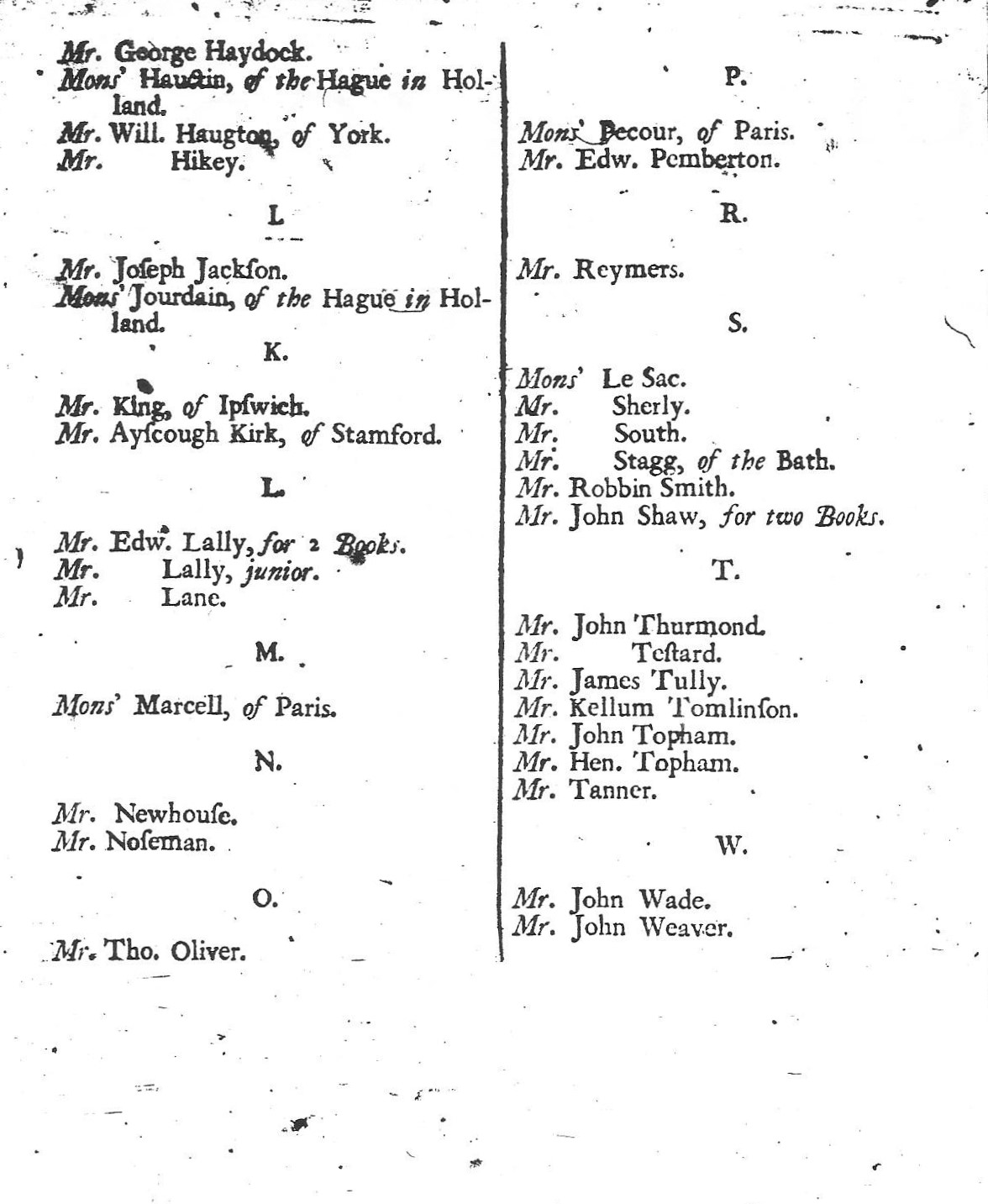

For Orchesography, Weaver evidently used the 1701 second edition of Feuillet’s Choregraphie with its ‘Supplement de pas’ (Feuillet had neglected to include the pas de menuet and contretemps du menuet, alongside a variety of other steps in the notation tables of his first edition). Weaver’s ‘Suplement’ is limited to minuet steps, including some of the ‘grace’ steps, but he also includes four pas composés which he attributes to Mr. Isaac.

Weaver’s claim that these steps are ‘seldom, or ever found in any other Dances whatsoever’ needs to be explored in detail. They aren’t in Feuillet’s step tables but it would be worth checking where and when they occur in dances other than those by Isaac.

Looking through the six dances, some other individual steps stand out. Here are some examples.

The Richmond

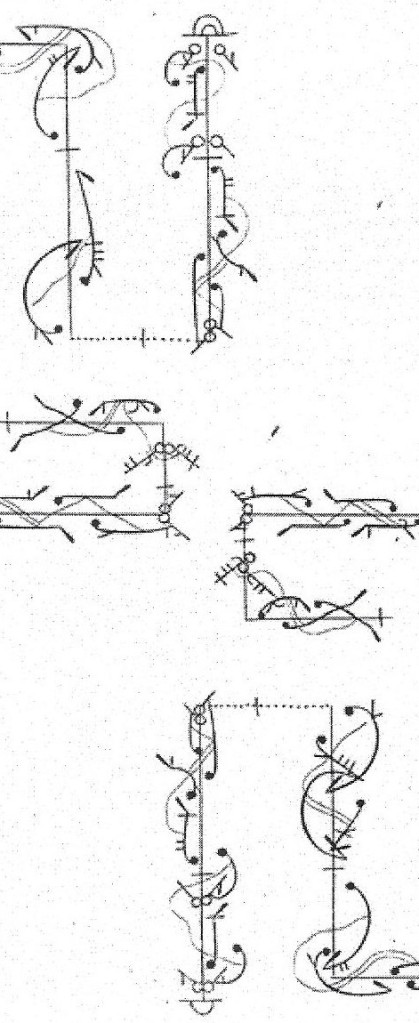

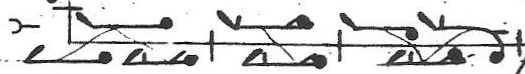

Plate 3 (an extension with variation of the jetté-chassé).

Plate 5 (the first pas simple continues that of the preceding pas composé, note the additional ornamentation on the right, the man’s side).

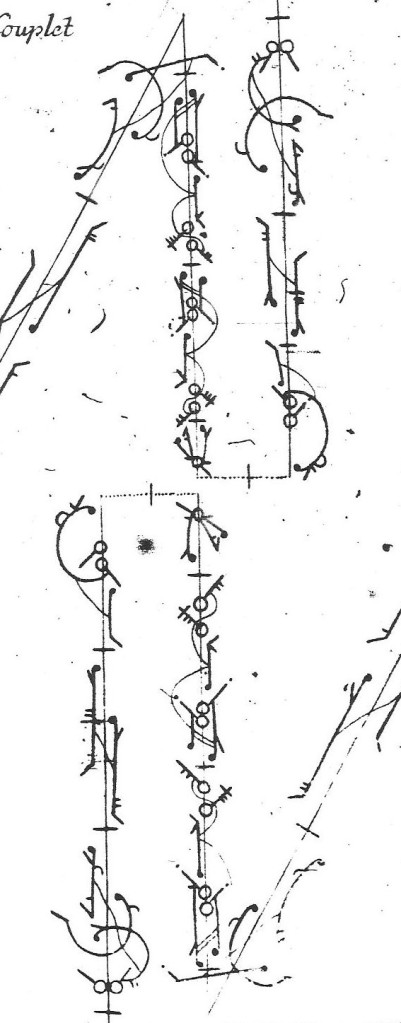

The Rondeau

Plate 1 (this can be described as a coupé battu with an added temps and is a step used in other dances. It comes from the opening triple time section).

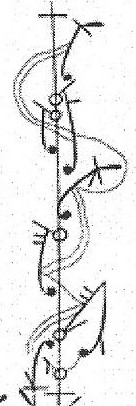

Plate 3 (a jetté followed by a coupé soutenue, but perhaps also related to Isaac’s fondness for the sort of variations shown in Weaver’s examples of his steps. This is from the second duple time section).

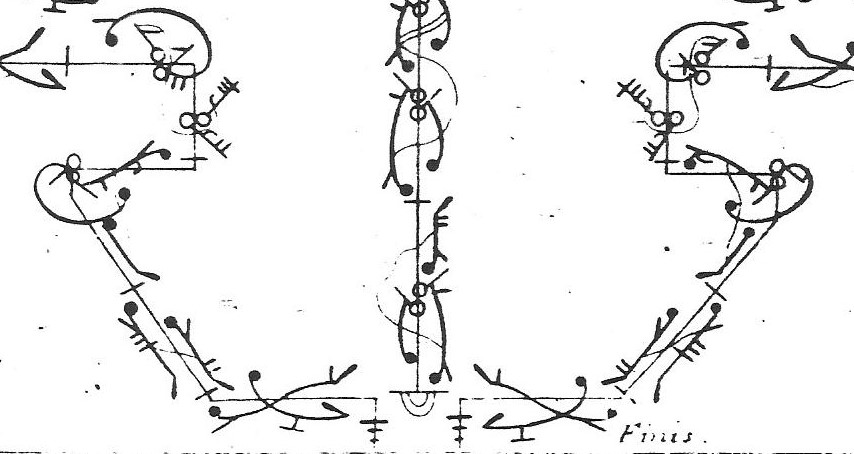

The Favorite

Plate 3 (two pas de bourrée with variations, from the chaconne).

The notation suggests subtle adjustments to the step as the foot moves, as well as directional changes in relation to the partner – assuming that it represents Weaver’s notation rather than the engraver’s interpretation of it.

Plate 5 (a coupé simple emboîté paired with a variant on the coupé avec ouverture de jambe, from the bourrée).

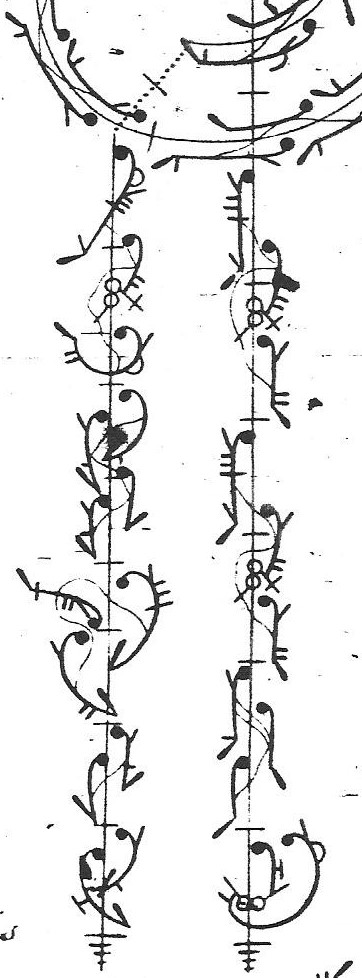

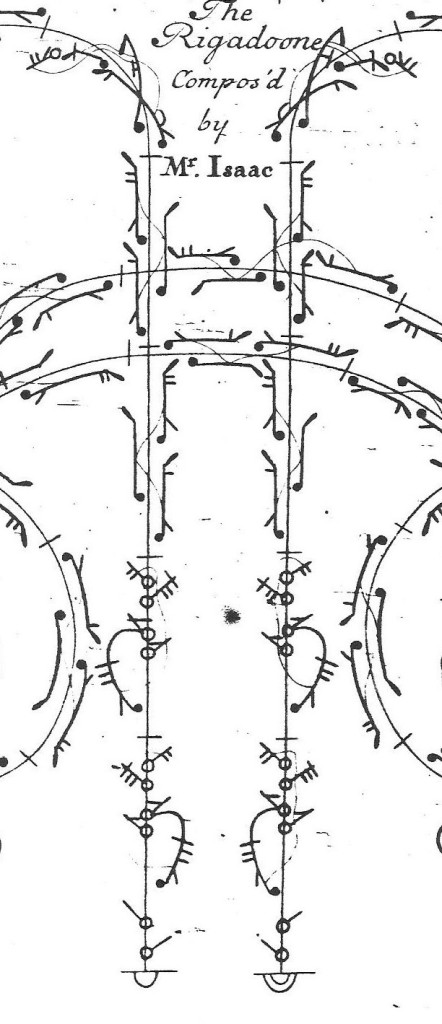

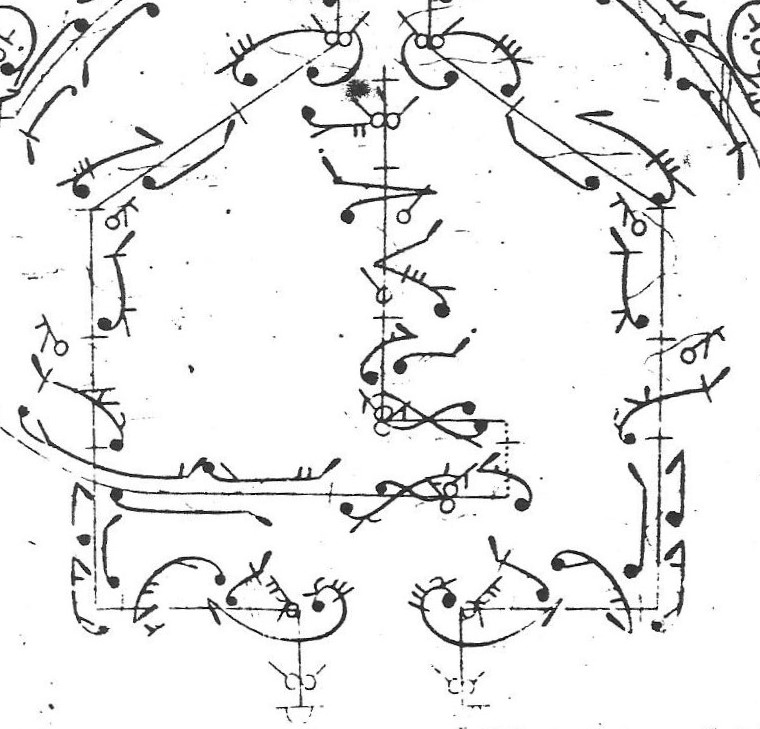

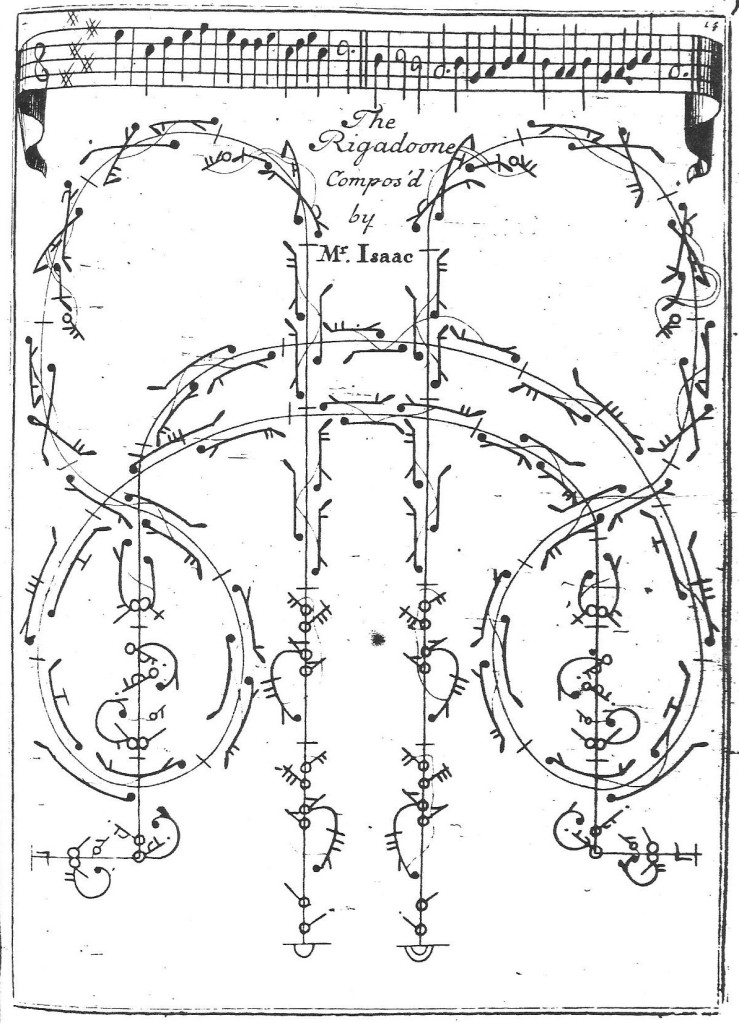

The Rigadoon

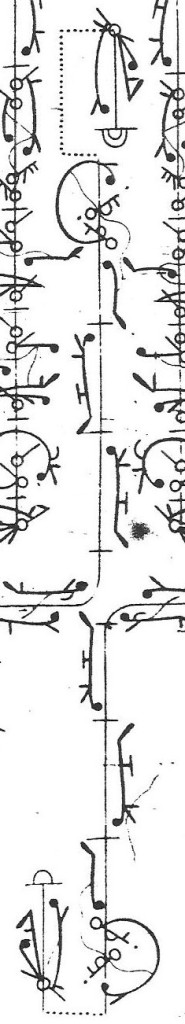

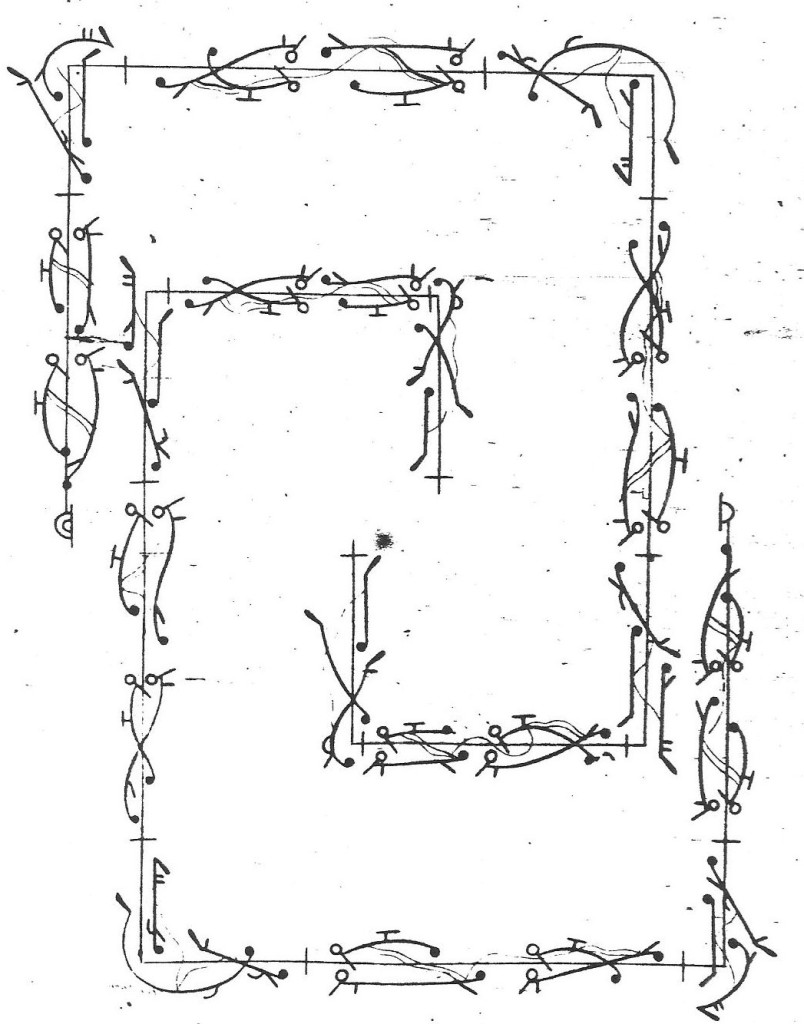

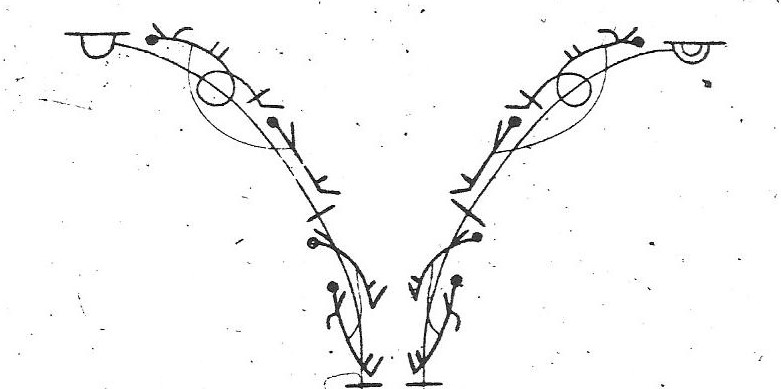

In The Rigadoon it is the sequences of steps that are unusual, rather than the individual pas composés. The most famous sequence is that of plate 2, with its glissades and pas de bourrée tracing a square or rectangular figure.

The glissades (paired coupés soutenues travelling sideways) are a feature of the step vocabulary of The Rigadoon and can be found in other dances as well, notably The Favorite.

There is also the rhythmic challenge posed by a sequence on plate 4. Three successive steps, each of which has a different number and placing of demi-coupés.

The couple travel sideways towards each other and are, at this point in the figure, quite close to the presence.

The Spanheim

Plate 3 (the two steps on the left can each be described as a pas de bourrée with a beat as well as the concluding jetté – here an assemblé – with added changes of direction).

The Britannia

Plate 1 (two jettés-chassés followed by a jetté, from the opening triple time section).

Plate 2 (a hop ornamented with a rond de jambe followed by a demi-coupé. The next step is two demi-coupés in succession. These are from the triple time section).

Plate 4 (two pas de bourrée with emboîté, ending in a plié leading to a sissonne, from the bourrée).

I hope to look at Isaac’s minuets in The Rondeau and The Britannia separately as both use a vocabulary of steps which go beyond the usual variations on and around the pas de menuet, contretemps du menuet and grace steps.

In all these steps, we can see Isaac not only constructing new pas composés from otherwise familiar elements, combining these in new ways, but also ornamenting these compound steps spatially as well as dynamically. It takes time and practice to master Isaac’s steps and sequences, which are an integral part of his idiosyncratic approach to the choreography of ballroom danses à deux.