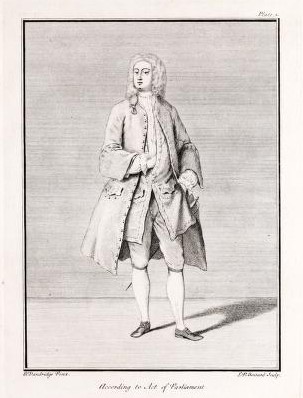

I have recently been revisiting John Weaver’s genres of dancing, as described in An Essay Towards an History of Dancing (1712) and revised in The History of the Mimes and Pantomimes (1728). In 1712, Weaver wrote that ‘A Master or Performer in Grotesque Dancing ought to be a Person bred up to the Profession and throughly [sic] skill’d in his Business’. A little further on in his text, Weaver continued:

‘As a Performer, his Perfection is to become what he performs; to be capable of representing all manner of Passions, which Passions have all their peculiar Gestures; and that those Gestures be just, distinguishing and agreeable in all Parts, Body, Head, Arms and Legs; in a Word, to be (if I may so say) all of a Piece. Mr. Joseph Priest of Chelsey. I take to have been the greatest Master of this kind of Dancing, that has appear’d on our Stage;’ (An Essay Towards an History of Dancing, pp. 166-167)

It is interesting that Weaver singled out an English dancer and dancing master in this context. The identity of ‘Joseph Priest of Chelsey’ and his relationship to the better-known Josias Priest, also closely associated with Chelsea, remain a mystery despite numerous attempts to discover exactly who they were (I list some of the articles that have addressed this conundrum at the end of this post).

My interest is in what made ‘Joseph Priest of Chelsey’ Weaver’s exemplar for grotesque dancing, a genre which he defines in a way which relates it to more natural ‘character’ dancing rather than the exaggerated masks of the commedia dell’arte with which it is now usually linked (and with which Weaver himself equated it in 1728). Although Richard Ralph, in his indispensable The Life and Works of John Weaver (London, 1985), says (on, p. 663) that ‘Weaver had not seen, and clearly did not know Priest, whose name was in fact Josias’, I think the opposite. Weaver’s first known billing on the London stage was in 1700, but it is likely that he arrived in the capital a few years earlier and so could well have seen Joseph Priest dance.

In this post, I want to concentrate on placing the little we know about the work of Josias and Joseph Priest on the London stage in a wider context. The difficulty with such an endeavour is the lack of evidence for the majority of performances given in London’s theatres between 1660 and the advent of the Daily Courant in 1702, after which the theatre companies began to advertise their daily programmes on a regular basis. The extent of the problem was succinctly set out by Robert D. Hume in his 2016 article ‘Theatre Performance Records in London, 1660-1705’. This is one underlying reason that we have only the following few references to go on.

15 August 1667, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Sir Martin Mar-all

‘This Comedy was Crown’d with an Excellent Entry: in the last Act at the Mask, by Mr. Priest and Madam Davies’. (John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, pp. 62-63)

18 February 1673, Dorset Garden, Macbeth

‘The Tragedy of Macbeth, alter’d by Sir William Davenant; being drest in all it’s [sic] Finery, as new Cloath’s, new Scenes, Machines, as flyings for the Witches; with all the Singing and Dancing in it: The first Compos’d by Mr. Lock, the other by Mr. Channell and Mr. Joseph Preist;’ (John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, p. 71. Many sources of the period use the spelling ‘Preist’ rather than ‘Priest’.)

June 1690, Dorset Garden, The Prophetess

‘The Prophetess, or Dioclesian an Opera, wrote by Mr. Betterton; being set out with Coastly Scenes, Machines and Cloaths: The Vocal and Instrumental Musick, done by Mr. Purcel; and dances by Mr. Priest;’ (John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, p. 89)

June 1691, Dorset Garden, King Arthur

‘King Arthur an Opera, wrote by Mr. Dryden; it was excellently Adorn’d with Scenes and Machines: The Musical Part set by Famous Mr. Henry Purcel; and Dances made by Mr. Jo. Priest;’ (John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, p. 89)

2 May 1692, Dorset Garden, The Fairy Queen

‘The Fairy Queen, made into an Opera, from a Comedy of Mr. Shakespears: This in Ornaments was Superior to the other Two; especially in Cloaths, for all the Singers and Dancers, Scenes, Machines and Decorations, all most profusely set off; and excellently perform’d, chiefly the Instrumental and Vocal Part Compos’d by the said Mr. Purcel, and Dances by Mr. Priest.’ (John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, p. 89)

Downes writes first of King Arthur, then The Prophetess and finally The Fairy Queen in three consecutive paragraphs. ‘Mr. Priest’ is thus ‘Mr. Jo. Priest’ for each of these dramatick operas. So, we have one single source for these five references, although John Downes is now generally thought to be reliable. There is another source of information about the activities of ‘Jo.’ Priest on the London stage, Thomas Bray’s Country Dances (London, 1699), which I will turn to in due course.

The first thing to note is that all of Downes’s references link Priest to Sir William Davenant, manager of the Duke’s Company, and his successor Thomas Betterton at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre and then Dorset Garden. Another is that, with the exception of the first, which belongs to the decade immediately following the Restoration of King Charles II, all the productions are forms of dramatick opera. So, one question to pursue is what Priest was choreographing, while another is which other such productions Priest might have been involved in.

There is every possibility that Priest was involved in earlier productions of Macbeth. Pepys attended a performance at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 19 April 1667 and remarked that it was ‘one of the best plays for a stage and variety of dancing and musique that ever I saw’ (I quote from the entry in The London Stage, 1660-1700). This was the season when, according to Downes, Priest danced in Sir Martin Mar-all at the same theatre. Macbeth is known to have been performed regularly between 1666-1667 and the new production of 1672-1673, so Priest could have been involved in the production over several years. The 1674 edition of the play indicates that much, if not all, of the dancing was associated with the Witches. We do not know who played the speaking Witches, but they may have been some of the male low comedians in the Duke’s Company. They may have been joined by professional dancers (again men) for the scenes with dancing. So, Priest and Channell may have danced as well as creating the choreographies.

Luke Channell’s career can be traced back to 1660, if not before. He was apparently the choreographer of Shirley’s masque Cupid and Death, performed with music by Matthew Locke and others in 1653, and Pepys records him as running a dancing school in Broad Street, London in 1660. He was sworn as dancing master to the Duke’s Company for the 1664-1665 season, a post he seems to have retained until at least 1674-1675. Channell could have introduced ‘Jo.’ Priest to the London stage and, in particular, to the company run by Davenant and then Betterton. By the time he worked with Priest on Macbeth, Channell must have been approaching fifty.

Another of Davenant’s productions of the same period that could have involved Priest was his adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. This was performed during the 1667-1668 season, when Pepys commented on the inclusion of dancing at several of the performances he attended including The Tempest, although he referred only to ‘the tune of the Seamen’s dance’ after seeing the play on 3 February 1668. The 1670 edition of The Tempest has a Dance of Devils in act 2, a dance of ‘eight fat Spirits’ in act 3, together with dances by characters in the play (rather than dancers) in acts 4 and 5. Again, Priest may well have danced in this production.

According to Downes, The Tempest was ‘made into an Opera by Mr. Shadwell’ during the 1673-1674 season (Roscius Anglicanus, p. 73). The 1674 edition of this new dramatick opera has a Dance of Winds in act 2, a Dance of Fantastick Spirits in act 3, a Dance by Spirits in act 4 and, finally, a Masque of Neptune and Amphitrite to end act 5. The number of dancers needed for this extravaganza is not easy to determine from the surviving text, but certainly included dances by four and then twelve Tritons in the final masque which may also have had dancing Winds and Nereids (undoubtedly with some doubling of roles). There is no evidence to tell us who danced, or who choreographed the dances, but in view of his work for Macbeth the previous season, surely Priest is a candidate for involvement in The Tempest. This production was regularly revived, as shown by the repeated entries even in the distinctly sparse information provided by The London Stage 1660-1700.

According to Downes, on 27 February 1675 (which he misdates to February 1673):

‘… The long expected Opera of Psyche, came forth in all her Ornaments; new Scenes; new Machines, new Cloaths, new French Dances: This Opera was splendidly set out, especially in Scenes; … It had a Continuance of Performance about 8 Days together, it prov’d very Beneficial to the Company; yet the Tempest got them more Money.’ (Roscius Anglicanus, p. 75)

This ‘Opera’ was essentially an adaptation by Thomas Shadwell of the comédie-ballet Psyché by Molière and Lully, first given at the Tuileries Palace in Paris on 17 January 1671 (New Style dating). There is no record of the dancers in the London production, but the choreography was by St. André and it is possible that they included some (if not all) of the French dancers who had performed in the English court masque Calisto first given just a few days earlier on 22 February 1675. I have written about Psyche and its dancing elsewhere (see the general references at the end of this post). The dancers in Psyche may have included ‘Jo.’ Priest, for there is a later record of a payment to Joseph Priest for service ‘by him performed’ in Calisto – the inference being (perhaps) that he danced in the court masque, although if he was the same man as the ‘Joseph’ Priest later recorded in Chelsea he may have been only in his teens.

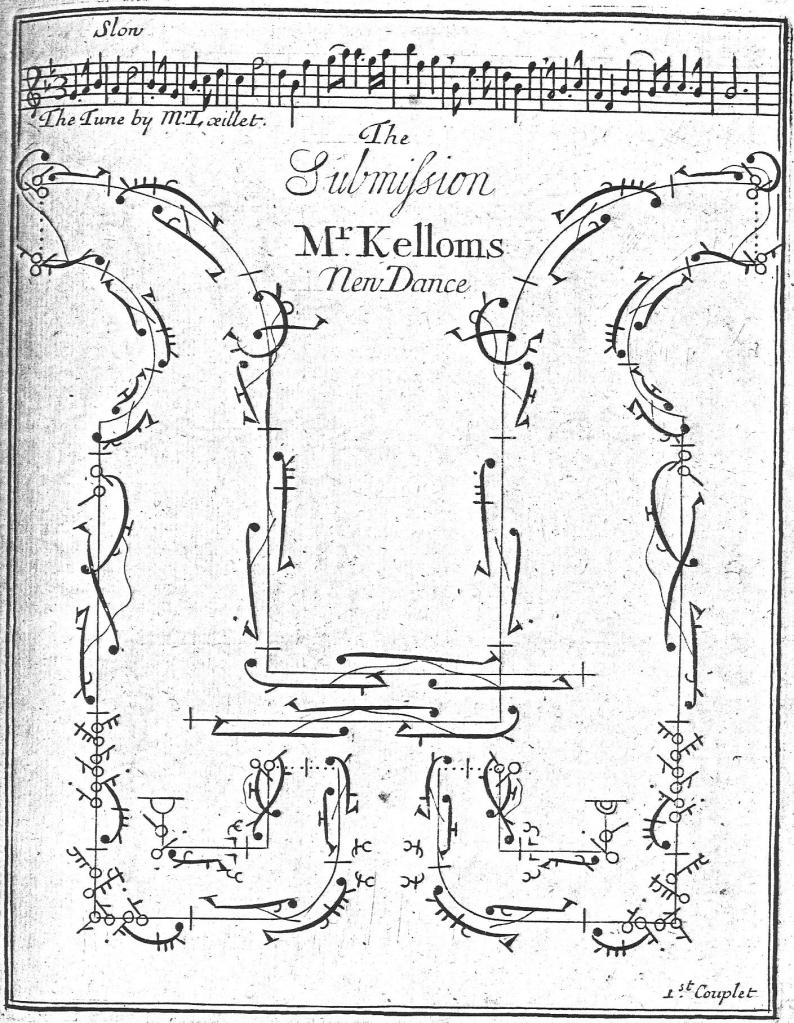

There are other productions during the 1670s and into the 1680s that are candidates for ‘Jo.’ Priest’s involvement, but I would like to jump forward to the 1690s and the plays and dramatick operas given in the wake of the success of Betterton and Purcell’s dramatick operas of the early 1690s. Here, I turn first to the source I mentioned earlier for clues. Part two of the 1699 first edition of Thomas Bray’s Country Dances has several references to members of the Priest family. It prints 39 dance tunes, of which number 7 is ‘The Spanish Entry Tune, and Dance compos’d by Mr. Josias Preist’ and number 16 is ‘An Entry by the late Mr. Henry Purcell, the Dance compos’d by Mr. Josias Preist’. The source for the ‘Spanish Entry’ is yet to be identified, but the ‘Entry by the late Mr. Henry Purcell’ is the dance for the Followers of Night in The Fairy Queen. Number 14 is ‘An Entry by the late Mr. Hen. Purcell, the Dance Compos’d by Mr. Preist’, this music is from The Indian Queen of 1695. Numbers 8 and 15, each with ‘the Dance compos’d by Mr. Preist’ have music from The Island Princess of 1699. The difference of name – ‘Mr. Preist’ instead of ‘Mr. Josias Preist’ – seems to point to Joseph Priest, suggesting at the same time that Josias was the choreographer of Purcell’s dramatick operas.

In 1695 Betterton had led a rebellion of the leading actors against the management of Christopher Rich, by then in charge of the United Company which had controlled both the Drury Lane and Dorset Garden Theatres since the merger of the King’s and Duke’s companies in 1682. Betterton and his fellow actors moved to the small, out-dated Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre which had been empty for some time. The Indian Queen and The Island Princess were both performed at Dorset Garden under Rich, which lends some credence to the idea that ‘Mr. Preist’ was Joseph and not Josias. Another source seems to point directly to Joseph Priest as working for Christopher Rich: Walsh’s The Second Book of Theatre Musick, published in 1699, includes an Entrée from act two of The Island Princess which it describes as danced by ‘Mr. Prist’.

Thomas Bray is named as dancing master for the United Company in 1689-1690 and again in 1693-1694 and he must surely have known both Josias and Joseph Priest. Bray is recorded as working for Betterton at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1694-1695, following the actors’ rebellion. He is identified as the choreographer for Europe’s Revels for the Peace, given at court on 4 November 1698 to celebrate the ending of the Nine Years’ War. Could ‘Mr. Preist’ have danced in that production?

The dancing characters in The Indian Queen are not easy to identify from the surviving sources. They seem to include the Followers of Envy in act 2 as well as Warlike Indians and Aerial Spirits at the beginning and then the end of act 3. The Island Princess is better documented and in act 2, which has the Entrée associated with Joseph Priest, the dancing characters are shepherds. The chacone belongs to the closing ‘musical Interlude’ The Four Seasons or Love in Every Age and accompanies the ‘Dutch-woman’ and ‘old Miser’ who personify Winter (both music and text are reproduced in the published facsimile cited below among the general references).

During the late 1690s, there were regular revivals at Drury Lane or Dorset Garden of several of the works I have mentioned as involving ‘Jo.’ Priest – The Indian Queen, The Prophetess and The Tempest in particular. There were also several new works at both of these theatres under Rich (as well as at Lincoln’s Inn Fields under Betterton) involving dancing. The most significant, in terms of its dancing, was Brutus of Alba first given at Dorset Garden in October 1696. This was essentially a pastiche drawing on earlier dramatick operas, including Albion and Albanius first given at Dorset Garden in June 1685 (another work with which ‘Jo.’ Priest might have been involved). Brutus of Alba did not outlast its first season and even its acting cast is unknown, but it included a dance of Statues as well as another dance for Harlequin men and women and Scaramouch men and women. If Joseph Priest did dance in these and other productions. Weaver could well have seen him take a variety of character roles and admired his performances.

The 1696-1697 season marked another new development in dancing on the London stage. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Betterton engaged Joseph Sorin, from the Paris fairs, as a dancer and dancing master and he would quickly be followed by other French dancers from the Paris Opéra. Anthony L’Abbé arrived during the 1697-1698 season and would enjoy a lengthy career in London. Claude Ballon made a brief visit – but a powerful impression – in 1698-1699. Between them, all three seem to have influenced London’s stage dancing to take new directions which may well have affected the career of ‘Jo.’ Priest among others. Detailed research into the dancing characters in plays, masques and dramatick operas given on the London stage in the late 17th century might help to unravel the mysteries surrounding ‘Jo.’ Priest, as well as contributing to a clearer understanding of the English and French influences on ‘character dancing’ in this period.

How does what I have set out so far help us with ‘Jo.’ Priest? I am strongly inclined to believe that Josias and Joseph Priest were two different individuals. The evidence surviving from parish registers tells us that Josias Priest and his wife Frances (usually called ‘Franck’) had at least ten children between 1665 and 1679. This suggests that they married around 1663 or 1664 and could place Josias’s birth in the years around 1640. By contrast, Joseph Priest and his unnamed wife had seven children between 1682 and 1693, pointing to a marriage in 1680 or 1681 and placing Joseph’s birth in the years around 1660. Josias and Joseph could have been father and son, or uncle and nephew, or even brothers. They could have worked together – with Josias as choreographer and Joseph as dancer – on the dramatick operas of the early 1690s when Joseph may have been in his early thirties.

Josias was apparently not involved in The Indian Queen. He may have decided to leave the London stage as relations worsened between Rich and Betterton (with whom he had worked for so long) but is it possible that it was he and not his son (also Josias) who was buried in Chelsea on 31 March 1692? He would thus have died while The Fairy Queen was in production, which seems possible but unlikely. However, it is interesting to note that advertisements for the Priest dancing school in Chelsea in A Collection for the Improvement of Husbandry and Trade from the issues of 1694-1695 onwards mention only ‘Mrs. Preist’ (I haven’t yet been able to access earlier issues of this newspaper or consult digitised images of the Chelsea parish registers to pursue this further). As I indicate above, I also wonder if Joseph Priest was a dancer rather than a choreographer, whereas Josias Priest was both earlier in his career. By the early 1690s, Josias was around fifty years old and more likely to have concentrated on creating rather than performing dances. Both Josias and Joseph Priest seem to have left the stage by 1700. No Priests are mentioned as dancers or dancing masters in London’s theatres in the following years, when the advent of the Daily Courant began to provide more information about dancers and dancing in London’s theatres.

In this post, I have speculated about fresh approaches to as well as different interpretations of the evidence surrounding ‘Jo.’ Priest and his involvement in dancing on the London stage. Unless fresh facts emerge about Josias and Joseph Priest, deeper and wider exploration of the context within which they worked seems to be the only way in which we might be able to shed new light on both of them.

Further Reading

On ‘Jo.’ Priest:

Selma Jeanne Cohen, ‘Theory and Practice of Theatrical Dancing: I Josias Priest’ in Famed for Dance, by Ifan Kyrle Fletcher, Selma Jeanne Cohen and Roger Lonsdale (New York, 1960), pp. 22-34.

David Falconer, ‘The Two Mr. Priests of Chelsea’, Musical Times, CXXVIII.1731 (May 1987), p. 263.

Jennifer Thorp, ‘Dance in late 17th-century London: Priestly Muddles’, Early Music, XXVI.2 (May 1998), pp. 198-210.

Josias Priest also merits entries in the Biographical Dictionary of Actors … 1660-1800, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Grove Music Online, among other such sources.

General:

John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, ed. Judith Milhous and Robert D. Hume (London, 1987).

Moira Goff, ‘Shadwell, Saint-André and the “curious dancing” in Psyche’, The Restoration of Charles II: Public Order, Theatre and Dance. Proceedings of a Conference held at Bankside House, London, on 23 February 2002, ed. David Wilson (Cambridge: Early Dance Circle, 2002), 25-33.

Robert D. Hume, ‘Theatre Performance Records in London, 1660-1705’, The Review of English Studies, 67.280 (2016), pp. 468-495.

Jennifer Thorp, ‘Dance in Opera in London, 1673-1685’, Dance Research, 33.2 (Winter 2015), 93-123.

The Island Princess. British Library Add. MS. 15318 (Tunbridge Wells, 1985)