I want to return to my series of posts on French dancers in London by revisiting the career of Francis Nivelon. He is one of the few such performers who have attracted research, with two papers published earlier in the 2000s (references are at the end of the post). Here, I would like to take a look at his origins and explore his work through just a few of his London seasons.

Francis Nivelon’s background and his unique skills are set out by François and Claude Parfaict in their 1756 Dictionnaire des théâtres de Paris:

‘Nivelon, fils du danseur dont on vient de parler [Louis Nivelon], & héritier de ses talens, après avoir brillé en differentes troupes de Province, & dans les pays étrangers, par différentes danses de caracteres, vint à Paris à la Foire S. Laurent 1728. & éxécuta dans la pièce d’Achmet & Almanzine, une Entrée de Paysan en sabots, avec une adresse admirable, toute la légéreté & la justesse possible, & dans les attitudes les plus burlesques & les plus contortionnées. Bien loin de faire paroître aucun effort, il sembloit qu’il mettoit de la grace par tout. L’air de violon qu’il dansa étoit de sa composition. Le Sieur Nivelon a continue encore les Foires suivantes, jusqu’à la fin de celle de S. Laurent 1729.’ (Vol. 3, p. 505)

They describe the elder Nivelon as ‘danseur du premier ordre pour la Pantomime’, recounting how he brought together a troupe of actors and dancers (which included Richard Baxter and Joseph Sorin) to appear at the Foire de S. Germain and the Foire de S. Laurent in Paris early in the eighteenth century. They also explain the bankruptcy of Louis Nivelon in 1711, adding that ‘Depuis ce temps là le Sieur Nivelon s’est retiré en Province’ (vol. 3, p. 505). The account of Louis Nivelon’s career points to the origin of Francis Nivelon’s skills. He presumably began dancing with and for his father, whose misfortunes may have been the factor that subsequently persuaded him to work in the French provinces and in London rather than in Paris. We can follow the London career of Francis Nivelon in some detail, but research into his work in France is yet to be pursued.

Francis Nivelon made his first appearance in London, with his younger brother Louis, at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre on 18 October 1723. The bills announced ‘several Entertainments of Dancing, both Serious and Comic, by the two Messieurs Nivelon, lately arriv’d from the Opera at Paris’ (Daily Courant, 18 October 1723). In this case, as in many others, the ‘Opera’ was actually Paris’s Opéra Comique established barely ten years earlier. Although the Parfaicts suggest that Francis Nivelon danced elsewhere, reaching the fair theatres in Paris only in 1728.

1723-1724 was John Rich’s tenth season at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the theatre that he had opened as a rival to Drury Lane in December 1714. The competition between the two playhouses had been fierce from the start and 1723-1724 marked the beginning of a new phase in their rivalry. The Drury Lane pantomime Harlequin Doctor Faustus opened on 26 November 1723, followed in short order at Lincoln’s Inn Fields by The Necromancer; or, Harlequin Doctor Faustus on 20 December. Francis Nivelon played the important role of the Miller and was also billed as Punch in The Necromancer, although he had been in Rich’s company for only two months. He appeared 51 times in the entr’actes and gave 61 performances in pantomime afterpieces – 112 performances in all, a total which became the norm for his London seasons.

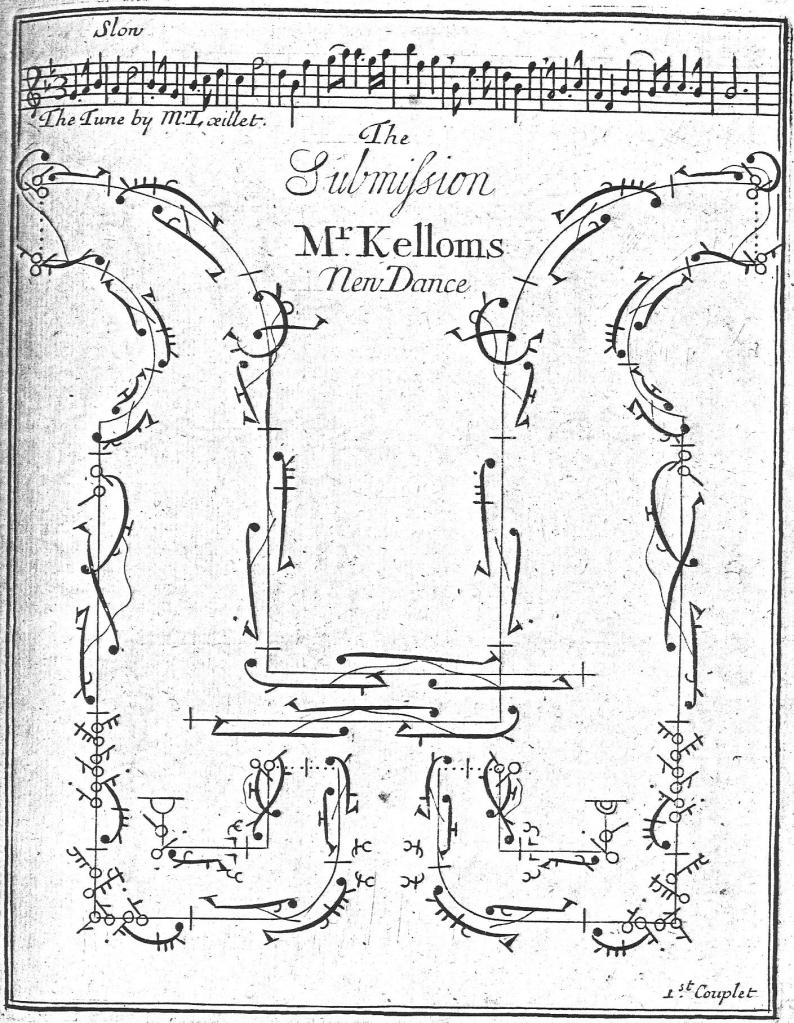

During the 1723-1724 season, Nivelon was billed in five solos in the entr’actes: Scating Dance in the Character of a Dutch Sailor; Flag Dance; Drunken French Peasant; Wooden Shoe Dance; and French Peasant (which may or may not have been the same as the Drunken French Peasant). He also danced four entr’acte duets; Running Footman’s Dance; Pierrots; French Peasant; and Wooden Shoe Dance. Pierrots was evidently an established duet danced with his brother, while the Running Footman’s Dance (which he performed with Mrs Rogier, soon to be Mrs Laguerre) may have been of his own composition. He performed the other two duets with Mrs Rogier, with whom he established a dance partnership that would last for several seasons. Nivelon did not introduce all of these dances to the London stage, but he certainly gave the older ones a new lease of life and in some cases, as with the Pierrots duet, set them up for lasting popularity with a series of dancers. This repertoire was reminiscent of the ‘différentes danses de caracteres’ mentioned by the Parfaicts.

In addition to his appearances in The Necromancer Nivelon also danced in another three pantomime afterpieces: Jupiter and Europa; or, the Intrigues of Harlequin, as Punch (Pluto); Amadis; or, The Loves of Harlequin and Colombine, as a Fury; The Robbers; or, Harlequin Trapp’d by Colombine, given a single performance for his brother’s benefit on 2 March 1724. In the last, Louis Nivelon was Pierrot, with Francis as Harlequin. He must have drawn on his established repertoire and past experience for these roles, as he may have done for those in The Necromancer. His casting, and his evident success in all of them, point to the appeal of his unique qualities as a performer.

Louis Nivelon did not return to London after 1723-1724, but Francis had evidently found a congenial as well as profitable milieu at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. He signed a contract at the end of the season to return for 1724-1725 at a salary of £5 per week and a benefit performance worth £100. This was far more than any of Rich’s other dancers were receiving and points not only to Nivelon’s engagement as the company’s dancing master but also to his close involvement in the creation of the dance repertoire, notably the comic parts of the pantomimes. However, the engagement did not run smoothly. Rich apparently refused to renew Nivelon’s contract at the end of 1724-1725, leading to a dispute between the dancer and the Harlequin-manager of Lincoln’s Inn Fields (the ensuing lawsuit is discussed in Thorp, ‘Pierrot fights back’).

This dispute was resolved and Nivelon continued to work for Rich every season until 1727-1728, commanding a high salary and a lucrative benefit. He added some entr’acte dances to his repertoire, notably a Clown solo (variously billed as a French Clown and a Dutch Clown in later years). He also took his share of the leading comic parts in the pantomime afterpieces at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. He was a Birdcatcher and Cerberus in Harlequin a Sorcerer: With the Loves of Pluto and Proserpine in 1724-1725, the Burgomaster in Apollo and Daphne; or, the Burgomaster Trick’d (with Francis and Marie Sallé in the title roles of the serious part) in 1725-1726, and the Yeoman in The Rape of Proserpine: With the Birth and Adventures of Harlequin (which also had the Sallés in serious dancing roles) in 1726-1727.

There is very little surviving evidence for the comic action in these pantomimes, and it is difficult to assess Nivelon’s roles in them. He was obviously a key participant in Apollo and Daphne, since he took the title role in the comic part (although the main comic character was Rich as Harlequin). In The Rape of Proserpine, the role of the Yeoman is undefined, except that the printed libretto places the first comic scene in ‘A Farm-Yard’, which could well have been the location for the famous birth of Harlequin (John Rich) from an egg, witnessed by Nivelon as the bemused farmer (see Lewis Theobald, The Rape of Proserpine (London, 1727), p. 4). From his first pantomime role, as the Miller in The Necromancer, Nivelon seems to have been the comic straight man to Rich’s Harlequin. The Parfaicts’ reference to Nivelon playing a tune he had composed himself also raises the possibility that he contributed to the ‘Comic Tunes’ used in the pantomimes. Such a range of talents would provide an explanation for the salary Nivelon was able to command from John Rich.

The 1727-1728 season at Lincoln’s Inn Fields was dominated by the success of The Beggar’s Opera, first performed on 29 January 1728 and given 62 times before the end of the season. There were dances in this new ballad opera, but no dancers were billed for any of the performances. Nivelon was explicitly advertised for only 83 performances, when he had been billed in well over 100 in most of his preceding seasons. His underemployment, and perhaps his fear that it would be repeated in 1728-1729, may have been among the reasons that he left Lincoln’s Inn Fields and returned to Paris. He did not come back to perform in London until October 1729. During his absence, Nivelon’s roles were taken by the Lincoln’s Inn Fields dancer Pelling (probably Edward Pelling, rather than Silvester as guessed by the writers of the Biographical Dictionary of Actors), except for the Burgomaster in Apollo and Daphne which went to the singer-actor John Laguerre.

According to the Parfaicts, Nivelon appeared at the Foire S. Laurent in 1728 and 1729. Apart from his ‘Entrée de Paysan en sabots’, evidently a version of the solo Wooden Shoe Dance he had been performing in London, they do not give other details of his repertoire. However, in their two-volume Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des spectacles de la foire (Paris, 1743), they draw on reports in the Mercure de France for July and August 1729 for two ballets that Nivelon performed with Monsieur Roger, Francis Sallé and others. One was ‘un Ballet singulier’ depicting love and jealousy, while the other was Noce Angloise. Nivelon mounted a version of the first as a successful afterpiece entitled The Dutch and Scotch Contention when he returned to Lincoln’s Inn Fields for the 1729-1730 season (for more information see my post Highland Dances in London). Noce Angloise seems not to have been offered to London audiences. This collaboration in Paris between dancers who worked for rival playhouses in London (Roger was dancing master at Drury Lane) calls for further research.

Nivelon probably returned to Lincoln’s Inn Fields during September 1729, to appear in The Necromancer when it was first billed on 29 September. This season, the new pantomime was Perseus and Andromeda; or, The Cheats of Harlequin (or, the Flying Lovers) performed on 2 January 1730. The complex title was an indication of the ongoing rivalry with Drury Lane, for it was a late response to Perseus and Andromeda: With the Rape of Columbine; or, The Flying Lovers by Roger, first given there on 15 November 1728. The Lincoln’s Inn Fields pantomime was initially advertised as Perseus and Andromeda; or, the Spaniard Outwitted, with the Spaniard (who later became a Hussar) played by Nivelon. It was given 59 times during 1729-1730. Nivelon picked up where he had left off in 1728, appearing in five pantomimes as well as his own afterpiece The Dutch and Scotch Contention and dancing in the entr’actes for a total of 121 performances.

Francis Nivelon continued to work for Rich until the 1732-1733 season, giving more than 110 performances with much the same repertoire in both 1730-1731 and 1731-1732. On 7 December 1732, John Rich opened his new Covent Garden Theatre, transferring the company’s plays and its entr’acte entertainments but not the pantomimes, as the new playhouse was not yet fully fitted out for their scenic complexity. Pantomimes continued to be given at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, less frequently than they had been in the preceding seasons. Rich faced challenges with running his old and new theatres simultaneously, but these paled into insignificance beside the turmoil at Drury Lane where changes in management following the death of actor-manager Robert Wilks in September 1732 led ultimately to a rebellion by a number of the leading players. Drury Lane’s season came to an abrupt end on 26 May 1733, when the licensees locked the players out of the theatre.

In 1732-1733, Francis Nivelon performed a full season, with a benefit on 27 March 1733. However, there must have been trouble behind the scenes, for he then left Rich and Covent Garden. He joined Drury Lane’s rebel actors, who were appearing at the Little Theatre in the Haymarket under the management of Theophilus Cibber, for the 1733-1734 season. It is difficult to guess why he did so. Rich relinquished Lincoln’s Inn Fields and his company played only at Covent Garden, where the main dance attraction was Marie Sallé who returned to London with her new dancing partner Malter. Even though there were fewer pantomime performances than usual at Covent Garden, Nivelon must surely have been worse off with the Drury Lane players both before and after their return to Drury Lane in early March 1734. He performed some of his most popular entr’acte dances, including his solo Wooden Shoe Dance and solo Clown, as well as the popular Pierrots duet (with another French dancer, Michael Poitier). He also appeared in The Burgomaster Trick’d, almost certainly a version of the comic part of the Lincoln’s Inn Fields pantomime Apollo and Daphne produced by him. The role of Harlequin in this afterpiece was played by another forain, the famous Monsieur Francisque (see Kenny, Monsieur Francisque’s Touring Troupe, pp. 178-187). Nivelon apparently gave 104 performances over the whole season but received no benefit.

Nevertheless, Francis Nivelon remained at Drury Lane for the 1734-1735 season, giving 97 performances (including a benefit on 19 April 1735) and playing the Country Squire in a successful new pantomime Harlequin Orpheus; or, The Magical Pipe. He may have been deterred from returning to Covent Garden because during 1734-1735 Rich shared his theatre with Handel’s opera company, which again reduced the number of pantomime performances. His choice to remain at Drury Lane may not have worked out quite as Nivelon hoped, for the season saw the return of George Desnoyer who immediately resumed his status as London’s leading male dancer, placing the emphasis on serious dancing.

On 24 September 1735, Nivelon was once again billed at Covent Garden. He appeared as the Miller in The Necromancer and his was the only name advertised for the first performance of that pantomime. He resumed his other pantomime roles and added a new one, that of the Doctor in The Royal Chace; or, Merlin’s Cave; With Jupiter and Europa which was first given on 23 January 1736 and performed 33 times before the end of the season. John Rich once again took his accustomed role of Harlequin. The Doctor had a wife, played by the actress and occasional dancer Mrs Stevens (who would later become John Rich’s third wife), and a servant performed by Lalauze (another French dancer who made a career in London). Nivelon also revived several of his popular entr’acte dances from earlier seasons, giving 135 performances in all. He was given a benefit on 20 March 1736 which brought in more than £110. All the evidence suggests that Rich remained well aware of Nivelon’s worth to the Covent Garden company and was glad to have him back.

Much the same pattern can be seen in the 1736-1737 season, but circumstances changed again during the following season. In 1737-1738, Nivelon was billed for only 68 performances, mainly because only two pantomimes were given at Covent Garden. This time, the culprit was The Devil of Wantley, an afterpiece that was given 67 times after its first performance on 26 October 1737. So far as Nivelon was concerned, this must have seemed like a repeat of 1727-1728 and The Beggar’s Opera. He appeared from 4 October 1737 to 16 May 1738 and enjoyed a benefit on 20 March 1738 (we do not know what the takings were). 1737-1738 was his last season on the London stage.

Nivelon had apparently been considering other avenues for his talents before the end of his final season. The Country Journal; or, The Craftsman for 21 January 1738 advertised ‘Proposals for publishing by subscription, the Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour … by F. Nivelon’, a work nearly ready for printing. The London Daily Post and General Advertiser for 11 July 1738 announced the work’s publication. Its appearance provides logic to the announcement in the London Daily Post for 17 January 1739 that:

‘Mr. Francis Nivelon, the famous French Dancer, has set up a School at Stamford in Lincolnshire, which is supported by all the Gentry in that Neighbourhood.’

This is, more or less, the last we hear of Nivelon. He turns up from time to time in a variety of later works and a subsequent edition of The Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour was advertised in the Public Advertiser for 13 December 1754, by which time he was ‘the late celebrated Monsieur Nivelon’. There is obviously far more to be discovered about the life of Francis Nivelon after he left the London stage.

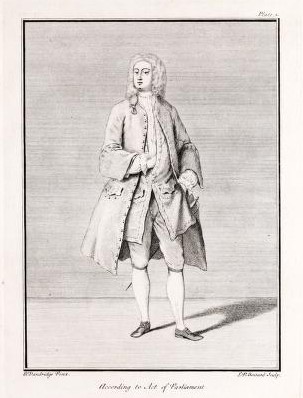

In this post, I have done little more than summarise Francis Nivelon’s career, knowing that he is worth a great deal more research. He may be one of the very few professional dancers of this period for whom we have a portrait. In The Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour, Nivelon declares that the figures of the Lady and Gentleman who grace its engraved plates are ‘taken from the Life’. So, was Nivelon himself the model for the gentleman? Is this the ‘Adroit and Elegant Monsieur Nivelon’?

Further reading:

Jeremy Barlow and Moira Goff, ‘Dancing in Early Productions of The Beggar’s Opera’, Dance Research, 33.2 (Winter 2015), 143-158.

Moira Goff, ‘The Adroit and Elegant Monsieur Nivelon’, in Dancing Master or Hop Merchant? The Role of the Dance Teacher through the Ages, ed. Barbara Segal (Salisbury, 2008), 69-77.

Moira Goff, ‘Evered Laguerre (1702-1739): The Career of a Forgotten English Dancer’, Dance Research, 43.2 (Winter 2025), 256-276.

Robert Kenny, Monsieur Francisque’s Touring Troupe (Woodbridge, 2025).

Jennifer Thorp, ‘Pierrot Strikes Back: François Nivelon at Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Covent Garden, 1723-1738’, in “The Stage’s Glory” John Rich, 1692-1761, ed. Berta Joncus and Jeremy Barlow (Newark, 2011), 138-146.

Other related posts on Dance in History:

Highland Dances on the London stage

Monsieur Roger, Who Plays the Pierrot

Who Was Francis Sallé?