One of the many challenges facing dance historians who (like me) specialise in ‘baroque dance’, and in particular stage dancing, is the rarity of opportunities to see performances of the notated choreographies. The most difficult of the surviving stage dances are rarely, if ever taught at historical dance workshops or courses here in the UK. I confess that I have been unable to find videos of performances of most of them online.

I have long been interested in Anthony L’Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances, thirteen choreographies created by him for professional dancers on the London stage notated and published around 1725 by F. Le Roussau. I have in my time performed four of them – the ‘Passacaille of Armide’, ‘Mrs Santlow’s Minuet’, the ‘Passagalia of Venüs & Adonis’ and the ‘Türkish Dance’ – and worked on another three – the ‘Chacone of Galathee’, the ‘Saraband of Issee’ and the following ‘Jigg’. However, until recently I had only seen four of them performed. When the chance arose to see three of the duets being taught in Paris as part of the Pecour Academy summer course 2025, I jumped at it. I am extremely grateful to Guillaume Jablonka and his fellow teachers Hubert Hazebroucq and Irène Feste for making an exception and allowing me to attend part of the course simply to watch and to learn. I have to say that it was a marvellous and truly rewarding experience.

The three choreographies were the ‘Loure or Faune’ danced by L’Abbé himself with his great compatriot Claude Ballon, the ‘Canaries’ performed by Charles Delagarde and Louis Dupré (the ‘London’ Dupré I wrote about a little while ago) and the ‘Passacaille of Armide’ danced by Mrs Elford and the very young Mrs Santlow.

Hubert Hazebroucq taught the ‘Loure or Faune’, Guillaume Jablonka the ‘Canaries’ and Irène Feste the ‘Passacaille of Armide’. The ‘Passacaille of Armide’ was one of the first baroque stage dances I worked on and inspired me to pursue the research which culminated in my book The Incomparable Hester Santlow. All three duets, particularly those for the men, are technically challenging and require teachers and dancers with an advanced level of training. The Pecour Academy was attended by dancers who were well up to the task.

The three teachers, all professional dancers, differ in their dancing styles and approaches to teaching, but all recognisably belong to a shared French tradition of historical dance research and reconstruction based on the concept of ‘la belle dance’. Their individuality as well as their shared heritage was apparent in their warm-up sessions and their teaching of the notated dances. I was able to observe their work during the last three days of the course and the focus and energy in all three classes was inspiring. The teaching and dancing I watched has raised many questions about my own knowledge and understanding of baroque dance, at one end of the spectrum in relation to the performance of individual steps and at the other about the interpretation of the dances in L’Abbé’s New Collection.

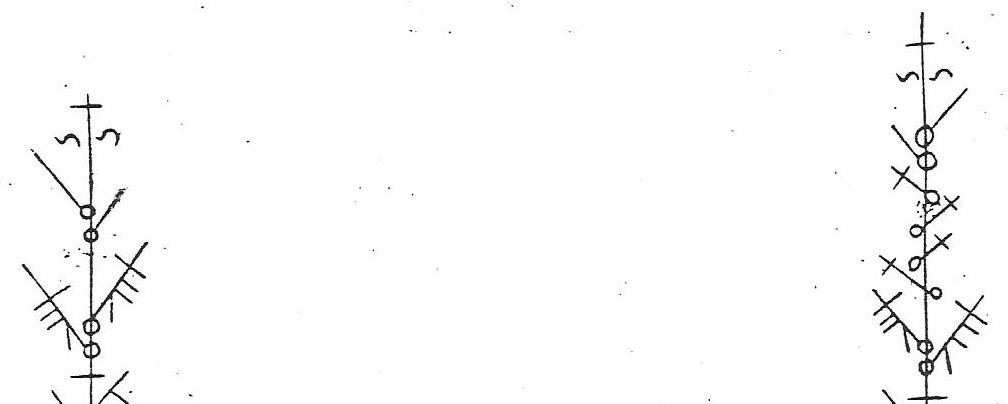

An abiding issue for all who study the dancing of the decades around 1700 (when Feuillet first published Choregraphie and the associated collections of notated dances) is what the notations leave out when it comes to technique as well as style. Some questions are answered (although not definitively) by the descriptions of steps in Pierre Rameau’s Le Maître a danser of 1725. For others there are no answers, at least in print. I was aware that French interpretations of Rameau differ from those in the UK and this course reminded me of details I had forgotten. It also revealed new thinking about steps that I was unaware of. I hope to be able to pursue some of these in individual posts for Dance in History.

Two other issues came up that require me to undertake far more research and do a great deal more thinking. One is about the way in which L’Abbé’s dances use space, which relates to the stages for which he created these choreographies in London (not in Paris, with the possible exception of the ‘Loure or Faune’ even though this was undoubtedly performed at London’s Kensington Palace). This issue is difficult to address in any course which has several couples of dancers learning dances in the same space, who necessarily have nothing like the area for which L’Abbé created each choreography and who are also engaging with the most difficult steps in the baroque vocabulary. There are also the relationships, expressive as well as spatial, between the two dancers and between them and their audience (which these students were certainly very aware of). The placing of that audience in relation to the dancers is also a factor to be investigated – I suspect that this differed in Paris and London. I hope to be able to explore all of these aspects more fully in due course. The second issue that arose is the characters personified by the dancers, which may or may not derive from the music used by L’Abbé. The three teachers understandably thought of these choreographies in the context of the works given at the Paris Opéra from which L’Abbé took his music. I (equally understandably, I hope) have tended to think of them in performance on the London stage, where they would have been removed from their original operatic context (which may well have been unknown to their London audiences). I think these two views, which can surely be reconciled despite their differences, provide a rich environment for the development of a range of interpretations.

I have focussed here on L’Abbé’s three choreographies, but each day included workshops on other dances and aspects of baroque dance. Notable among these was Christine Bayle’s masterclass on Pecour’s La Nouvelle Forlane, in which she shared her great skill, experience and knowledge with a group of of dancers who were eager and extremely well prepared to benefit from it. That was a special moment, too. The whole course concluded with a public presentation of the dances that had been taught over the week. It was described as showing ‘Work in Progress’, but what marvellous Work – and fantastic Progress – it shared. I salute the teachers and their students for a wonderful achievement.

The 2025 Pecour Academy was a while ago now, but I am still thinking about it as I pursue my research into L’Abbé’s stage dances. I repeat my grateful thanks to Guillaume, Hubert and Irène for sharing their work with me.