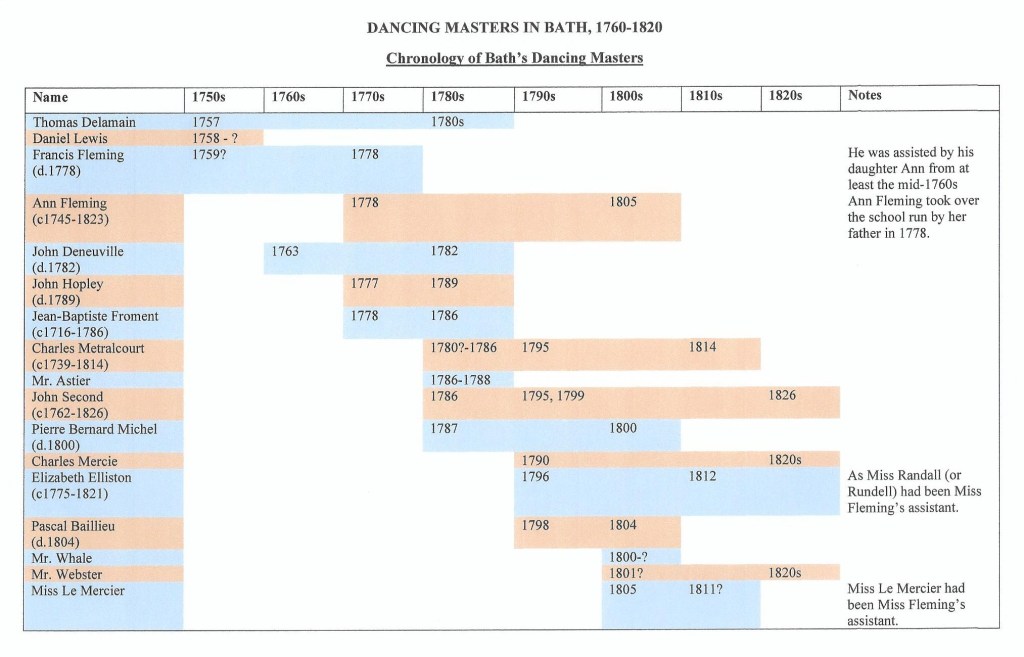

A little while ago, I did quite a bit of research into dancing masters working in Bath as part of a project relating to the Upper Assembly Rooms there. My starting point was Trevor Fawcett’s article on the subject, published in 1988 but still a comprehensive and immensely valuable resource for subsequent work. One of the interesting things that emerged was the number of dancing masters in that city who were French and had worked in London’s theatres. I wrote a little ‘biographical dictionary’ with brief details of each of Bath’s dancing masters based there between the 1750s and the 1820s and I compiled a chart showing approximately how long each of them worked there and how their careers overlapped.

This study also relates to my separate investigation of French dancers in London during an earlier period (my recent post Monsieur Roger, Who Plays the Pierrot began what I hope will be a short series on them).

Apart from the article by Trevor Fawcett, much of my information about their work in Bath came from advertisements published in the Bath Chronicle, while details of their stage careers were mainly drawn from the volumes of The London Stage, 1660-1800 and the Biographical Dictionary of Actors (both referenced below). Far more detailed research, using a much wider range of archives, is needed to fill out the details of the lives and careers of Bath’s dancing masters and to ensure that all of them have been identified and their backgrounds charted.

John Deneuville seems to have arrived in Bath in the early 1760s. His advertisement in the Bath Chronicle for 31 March 1763 declares that he is ‘from the Opera in Paris, and last from the Theatres in London’. A few years later, in the Bath Chronicle for 24 September 1767, his advertisement says that he

‘having been at Paris during the late Vacation, proposes to teach the new Dances called the Minuet-Dauphin, and the Forlane, composed by Mr. Marcel Dancing-Master of the French Court; also the newest French Country dances, with the proper Steps of the Cotillion and Allemands, now in Vogue at Paris.’

Despite his reference to the Paris Opéra, home to the most famous ballet company in Europe, Deneuville may in fact have come from Paris’s less exalted Opéra-Comique – like so many of the French dancers who came to London at this period. There is no mention of his name in the Index to the London Stage, suggesting that either he was simply a supporting dancer in London’s principal theatres, or that he danced at venues beyond Drury Lane and Covent Garden. Deneuville taught in Bath for nearly 20 years. He died in 1782 and was buried there.

Jean-Baptiste Froment arrived in Bath to teach dancing in 1778. His advertisement in the Bath Chronicle for 25 June 1778 set out his credentials and what he intended to teach. He claimed to have been taught in Paris by Monsieur Marcel and to have himself taught at ‘the most eminent Academies’ in London. He offered tuition in:

‘all the fashionable Dances now in Vogue in London and Paris, viz. the Minuet in the present Taste, the Louvre, Minuets Dauphin, de la Reine, Allemandes, Cotillons, … and particularly that graceful Minuet de la Cour and Gavot.’

Froment had been a dancer in London’s theatres. His first billing (but probably not his first performance in London) was at Drury Lane on 10 March 1739, when he danced in the pantomime Harlequin Shipwreck’d. He seems mainly to have been a supporting dancer and his earlier career, presumably in France, is yet to be uncovered. Froment pursued his London career at the Sadler’s Wells and Goodman’s Fields theatres, as well as at Drury Lane, Covent Garden and the Haymarket Theatre. By the end of his stage career in 1777 his performances were limited to appearances with his daughter Mrs Sutton at her annual benefits (she was a dancer at Drury Lane). Froment’s career in London had not been straightforward, for in 1746 – in the wake of the 1745 rebellion – he had been identified as a Jacobite sympathiser, an accusation he was able to rebut. Froment taught in Bath and in London until the 1780s. He died in Bath in 1786 and was buried in Bath Abbey on 13 April.

In 1787, Pierre Bernard Michel opened his dancing school in Bath. His advertisement in the Bath Chronicle for 11 January 1787 informed ‘the Nobility and Gentry of the Cities of Bath and Bristol, that he has been one of the first Dancers, at most of the Courts in Europe, and at the Opera-House in London’. Michel may have been the ‘Master Mechel’ who had first appeared in London on 22 December 1739 at Covent Garden. He and his sister danced a varied repertoire and were very popular for three seasons, and Michel would later pursue a successful dancing career throughout Europe. He may well be the dancer referred to by Gennaro Magri, in his Trattato Teorico-Prattico di Ballo published in Naples in 1779, as ‘the best Ballerino grottesco that France has produced’. In Bath, Pierre Bernard Michel was assisted by his daughter Lucy, but when she married and became Mrs de Rossi she set up her own dance classes, provoking a serious quarrel with her father. This was played out, in part, through their competing advertisements in the Bath Chronicle. Lucy would later marry the dancer and dancing master James Byrne, well-known in London in the years around 1800. Her father’s final years are yet to be fully researched, but he is known to have died in Melksham in 1800.

There were two other dancing masters in Bath who, if they were not in fact French, seem to have had close links to French dancers appearing in London’s theatres. Charles Metralcourt was teaching in Bath by 1782, the year he advertised the opening of ‘his Academy’ in the Bath Chronicle for 28 March.

Fawcett describes him as a ‘versatile dancer and a ballet-master at the London Opera house’ (presumably referring to the King’s Theatre) without citing a source. He may have been the ‘Mettalcourt’ who appeared in ‘a new grand Polish Dance’ in the entr’actes at Covent Garden on 5 December 1780, described as making his first appearance at that theatre. Metralcourt did not generally refer to his connections with London’s theatre world in his advertisements. Notices in the Stamford Mercury indicate that he was working as a dancing master in Stamford between 1775 and 1780. He taught in Bath until 1786 and an advertisement in Saunders’s News-Letter for 29 November 1786 declares that he was teaching in Bath during the winter season and in Belfast during the summer season. After leaving Bath in 1786 (apparently as a result of the arrival of the of the dancing master John Second that year) he seems to have taught in Dublin and in Ipswich. He returned to Bath in 1795, taking over from Second and he continued to teach and to hold balls for his pupils at the Upper Assembly Rooms until 1811. Charles Metralcourt died in 1814 and was buried in the Catholic Burial Vault, Old Orchard Street, Bath on 12 October 1814.

John Second (who may or may not have been French) was invited to take over Jean-Baptiste Froment’s school in 1786, as he advertised in the Bath Chronicle for 18 May 1786 describing himself as ‘Of the King’s Theatre, but late of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and Sole Assistant to Mr. Vestris, Senior’. His name appeared occasionally in advertisements for performances at the Covent Garden Theatre during the 1782-1783 season and at Drury Lane in 1783-1784. He may well have appeared more often, but was not important enough to be named in the bills. If he was indeed ‘Sole Assistant’ to Vestris Senior, Gaëtan Vestris, it must have been in the 1780-1781 season at the King’s Theatre during the first visit of the celebrated French dancer (who did not return until 1790-1791). Among the ballets mounted by Vestris Senior was Ninette à la Cour, with the Italian ballerina Giovanna Baccelli in the title role and Gaëtan’s son Auguste Vestris as her lover Colas. First given on 22 February 1781, it was an enormous success and the cast was printed – together with a synopsis of the ballet – in the Public Advertiser for 26 February 1781.

Second was not among the named dancers. He may have been one of the ‘Figure Dancers’ referred to simply as a group, or danced as one of the individual characters for whom no performers’ names are given. No evidence has yet come to light to support Second’s claim that he was Vestris Senior’s assistant, or to suggest why he might have been given that role. Second apparently left Bath in 1795, when his teaching practice was taken over by Charles Metralcourt, although he seems to have returned in late 1799. His subsequent career as a dancing master awaits further research, but he was buried at St James, Bath on 23 January 1826 (when his name was recorded as Paul John Second).

The most celebrated teacher of dancing in 18th-century Bath was half-French. Ann Teresa Fleming was the daughter of Irish violinist Francis Fleming and French dancer Ann Roland, younger sister of the well-known dancer Catherina Violanta Roland. Both girls danced in London for a number of seasons. Ann Teresa Fleming was never a stage dancer but built a very successful career teaching ballroom dancing. I wrote about her in my post Lady Dancing Masters in 18th-Century England but there is far more to say than I could include there.

Bath is a special case when it comes to the history of dancing. As the most fashionable spa in England, it was big enough to attract a number of dancing masters to teach the aristocracy and gentry who gathered there and attended the regular balls in both the upper and lower assembly rooms. It is surely significant that many of these dancing masters were French and had backgrounds in the theatre (it is worth noting that the dancing at the Theatres Royal in Bath and Bristol is yet to be researched). Bath was much smaller than London, providing an opportunity to chart in detail the community of dancing masters and their clientele, as well as the dancing that happened there and the wider social context which brought it all together. Far more research is needed to help us understand who was who and how it all worked.

References:

Trevor Fawcett, ‘Dance and Teachers of Dance in Eighteenth-Century Bath’, Bath History, 2 (1988), 27-48.

Philip J, Highfill Jr, Kalman A. Burnim and Edward A. Langhans. A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800. 16 vols. (Carbondale, 1973-1993)

Index to the London Stage, compiled, with an introduction by Ben Ross Schneider, Jr. Second printing (Carbondale and Edwardsville, 1980)

The London Stage, 1660-1800. 5 Parts (Carbondale, 1960-1968).

Part 1: 1660-1700; Part 2: 1700-1729; Part 3: 1729-1747; Part 4: 1747-1776; Part 5: 1776-1800.

A calendar of stage performances at London’s major theatres, with a detailed introduction to each part.

Gennaro Magri, translated by Mary Skeaping. Theoretical and Practical Treatise on Dancing (London, 1988).

See p. 160 for the reference to Pierre Bernard Michel.