‘There have been companies of Pantomimes raised in England; and some of those comedians have acted even at Paris dumb scenes which everybody understood. Tho’ Roger did not open his mouth, yet it was easy to understand what he meant.’

This quotation from Jean-Baptiste Dubos’s Réflexions critiques sur la poesie et sur la peinture, as translated by Thomas Nugent in 1748, is well-known. Roger himself is hardly known at all, yet his career is of great interest not only as part of the history of the English pantomime but also for what it tells us about theatrical exchange between Paris and London in the early 18th century.

Roger was probably the ‘Person, who plays Pierot at Paris, is just arrived from thence, and will perform this night’ advertised to appear at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre on 29 January 1719. He was joining Francisque Moylin’s company, which had been playing there since mid-November 1718 and would stay until 5 February before moving on to perform at the King’s Theatre until 21 March 1719. He presumably took the title role in the French three-act farce Pierot maître valet, et l’opera de campagne, ou la critique de l’opera. Roger was given a benefit on 5 February 1719, commanded by the Prince of Wales, at which he performed an acrobatic stunt (apparently as Octave in a one-act farce titled Grapignant; or, the French Lawyer) and ‘the Scene of the Monkey, which has never been performed in England before’. His mimetic and acrobatic skills had probably been acquired through his training and experience as a performer at the Paris fairs.

Roger returned to London in the spring of 1720, playing in De Grimbergue’s company at the King’s Theatre (which alternated its performances with those of an Italian opera company). He returned, again with De Grimbergue, for a season at the newly opened Little Theatre in the Haymarket between December 1720 and April 1721, after which he did not return to London until 1725. The Biographical Dictionary of Actors states that he was appointed as ballet master at the Opéra-Comique in Paris by its manager, the English Harlequin Richard Baxter, but gives no source for this assertion. It also repeats the suggestion by Ifan Kyrle Fletcher, in Famed for Dance, that Roger may have been an Englishman. Fletcher likewise offers no evidence for this and may simply have been misinterpreting the passage from Dubos referring to Roger. Further research is needed to see what can be discovered about Roger in French records, although I cannot pursue this here.

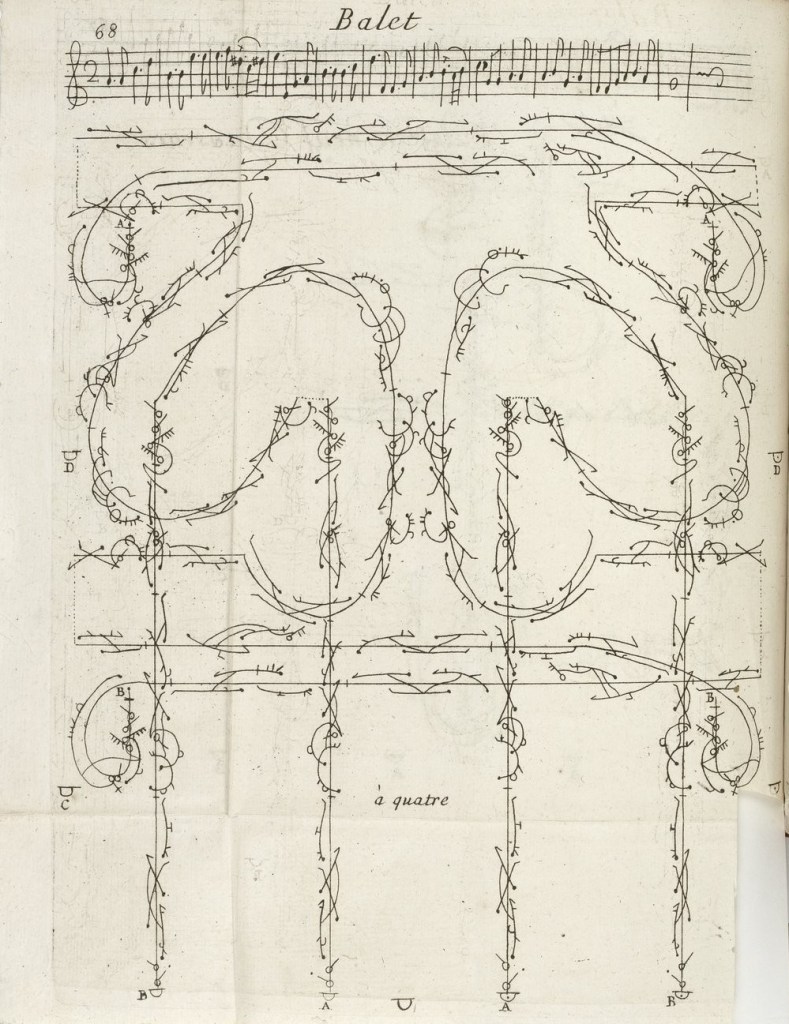

A new troupe of ‘Italian Comedians’ was billed at the Little Theatre in the Haymarket between 17 December 1724 and 13 May 1725. ‘Roger, the Pierrot’ was first advertised on 22 January 1725, as the creator of ‘un ballet nouveau’ given as part of a performance which included Molière’s Le Medecin malgré lui and Gherardi’s Les Filles errantes. Later in the season, he was billed as the creator of a ‘Nouveau ballet comique’ as well as a performer in a ‘Variety of new Dances’ and gave Pierrot and Country Dance solos. His benefit was on 18 March 1725 and included ‘Pierrot Grand Vizier, with the Turkish Ceremony of the Bourgeois Gentilhomme’ and ‘a new Sonata on the Violin of Mr. Roger’s composing, by himself’.

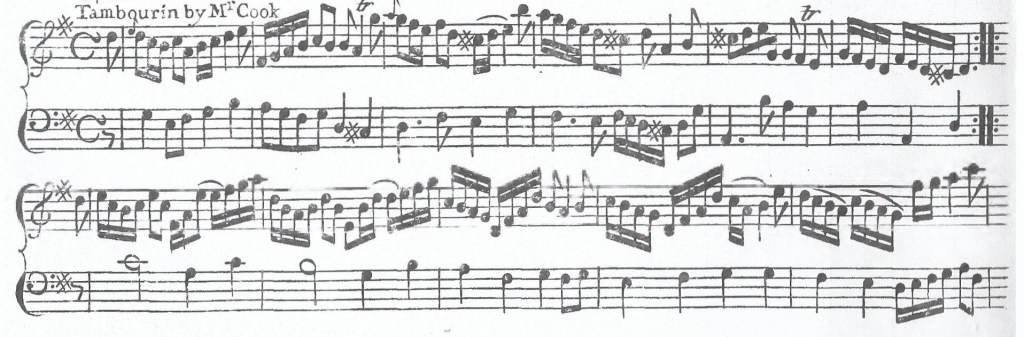

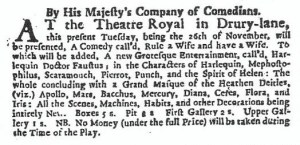

Although companies of ‘Italian Comedians’ would return to play in London during the 1725-1726 and 1726-1727 seasons, Roger did not appear with them for he had joined the company at the Drury Lane Theatre, where he was first advertised on 28 September 1725. The bill published in the Daily Courant on that date recorded his latest new dance.

La Follett (as it was first called) had already been advertised at Drury Lane on 23 September 1725, with no mention of the performers. Roger must surely have danced it then, and if it marked his first appearance with the company it is interesting that no mention was made of this.

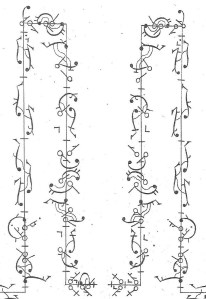

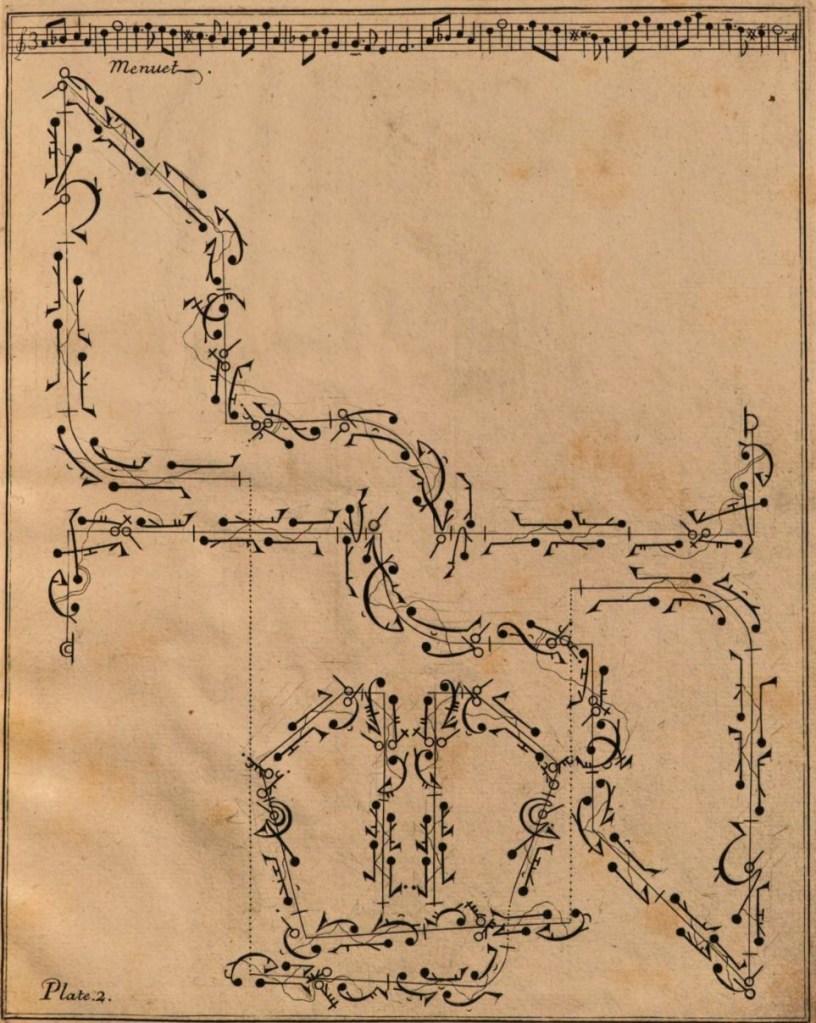

In his first season at Drury Lane, Roger was billed in three solos, a duet, three group dances and three pantomimes. The solos were variations on the ubiquitous Peasant dance – a Peasant (28 October 1725), a Drunken Peasant (3 November 1725) and a French Peasant (13 May 1726). He was billed in a Drunken Peasant again in 1728-1729, but he seems not to have repeated the first two dances in later seasons. The duet, usually advertised as La Pieraite and created by Roger himself, was first given on 21 March 1726 and immediately became a staple of the entr’acte dance repertoire. It was performed every season until 1730-1731 by Roger, first with Mrs Brett and then with Mrs De Lorme, and was presumably a ‘Pierrot’ dance. This season also marked the first performances of Roger’s group dance Le Badinage Champetre, billed on 19 November 1725, in which there were five couples led by Roger and Mrs Booth. This dance was also popular and remained in the entr’acte repertoire until 1729-1730.

Drury Lane had lost its leading male dancer, the multi-talented John Shaw, who was absent from late in the 1724-1725 season and died in December 1725. Shaw had been the company’s Harlequin and had created that role in John Thurmond Junior’s The Escapes of Harlequin (first given 10 January 1722) and the overwhelmingly successful Harlequin Doctor Faustus (first given 26 November 1723). Drury Lane’s managers understandably wished to keep both pantomimes in the theatre’s repertoire, not least to counter the rivalry of John Rich at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and seem to have given Roger the opportunity to try out the role of Harlequin in both pantomimes. The experiment (if that is what it was) was unsuccessful. The Escapes of Harlequin was not revived again and Roger instead took over the role of Pierrot in Harlequin Doctor Faustus, which he played regularly until 1730-1731.

In his first season at Drury Lane, Roger also took over the role of Pierrot in Thurmond Junior’s Apollo and Daphne; or, Harlequin’s Metamorphoses (first given under the title Apollo and Daphne; or, Harlequin Mercury in 1724-1725). He continued to dance in the pantomime until 1727-1728. Apollo and Daphne made a final appearance as a ‘Scene’ within a ‘New Entertainment’ The Comical Distresses of Pierrot which was given a single performance at Drury Lane on 10 December 1729. Roger played Pierrot, suggesting that the piece may have been created by him.

Roger danced at Drury Lane for six seasons, until his untimely death in 1731, and built a successful career there as both a choreographer and a dancer within the company. After his first season, he seems to have mainly appeared in pantomime afterpieces. He worked with John Thurmond Junior again in 1726-1727, as Pierot in The Miser; or, Wagner and Abericock, which was revised and re-titled Harlequin’s Triumph later that season. He then went on to create a number of pantomimes himself. Harlequin Happy and Poor Pierrot Married, first given on 11 March 1728, brought him and John Weaver together on stage for the first time. Weaver, who had not appeared in London since 1721, played Colombine’s Father, while Roger took his accustomed role of Pierrot. The pantomime lasted until 1729-1730 (with cast changes) and was revived for a single performance at Drury Lane on 4 December 1736.

Far more important was Perseus and Andromeda: With the Rape of Colombine; or, the Flying Lovers first given at Drury Lane on 15 November 1728 and successful enough to persuade John Rich to mount a rival production at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 2 January 1730. The Drury Lane version was ‘In five different Interludes, viz. Three Serious, and two Comic’ and the scenario published to accompany performances stated that the serious part was by Roger and the comic part by John Weaver. Both Roger and Weaver appeared in the comic part, Roger as Pierrot (Doctor’s Man) and Weaver as Clown (Squire’s Man). From 15 March 1729, the comic part was changed to ‘the Devil upon Two Sticks’ and the new edition of the scenario (again published to accompany performances) made clear that this was by Roger. Here are the title pages of the two editions.

Weaver had no role in the new comic plot and may have already decided to leave London by the end of the season. He had a shared benefit on 25 April 1729, at which he danced a Clown solo and Roger reprised his solo Drunken Peasant (perhaps an indication that there were no hard feelings between the two men over the change to the comic part of Perseus and Andromeda). Weaver’s last billing was on 2 May 1729 and he would not return to work in London until 1733. It is worth noting that in the serious part of Perseus and Andromeda Roger followed Thurmond Junior’s Apollo and Daphne in giving the title roles to two dancers.

The next of Roger’s afterpieces was wholly serious. Diana and Acteon was given on 23 April 1730 for Roger’s benefit, with Mrs Booth and Michael Lally in the title roles (they had also danced the title roles in Perseus and Andromeda). The afterpiece was not revived until 1733-1734, when it had two performances the first of which was as part of a benefit for Mr and Mrs Vallois. She was Roger’s widow and she repeated her role as one of the Followers of Diana, with Mrs Bullock as Diana and Vallois as Acteon.

Roger’s last afterpiece for Drury Lane was by far his most successful and the theatre’s most popular production for many years. Cephalus and Procris: With the Mistakes received its first performance on 28 October 1730. Like Perseus and Andromeda, the comic part was quickly changed – the ‘Dramatic Masque’ (as it was described in the bills) was advertised on 4 December 1730 with ‘a new Pantomime Interlude’ as Cephalus and Procris: With Harlequin Grand Volgi. This pantomime had seventy-four performances in its first season and continued to be played until 1734-1735. Roger was Pierrot, a role that went to Theophilus Cibber after his death. Cephalus and Procris broke new ground for Drury Lane by copying John Rich’s practice of giving pantomime title roles to singers. It may also have influenced John Weaver when he returned to Drury Lane in 1733 to mount his last ‘Dramatick Entertainment in Dancing and Singing’ The Judgment of Paris.

Without further research, I cannot tell whether Roger returned to Paris regularly each summer to perform at the Opéra-Comique and the fairs when Drury Lane was closed. He did play at the Opéra-Comique in July and August 1729, for the Mercure de France mentions him performing in two ballets given as divertissements within La Princesse de la Chine. The first was a ballet on the subject of ‘l’Amour et la Jalousie’ on 7 July 1729 and the writer was obviously convulsed by Roger’s performance.

‘Le Sieur Roger, qui a composé les pas du Balet, & dont la seule figure est capable de faire éclater de rire le plus grand stoïcien’

The piece Love and Jealousy given at Drury Lane on 18 October 1729, with no information other than its title in the bills, may well have been by Roger. The Opéra-Comique ballet was also the source for The Dutch and Scotch Contention; or, Love and Jealousy given at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on 22 October 1729. For more information about this afterpiece, which may have been by Francis Nivelon, see my post Highland Dances on the London Stage (21 February 2021) which transcribes in full the report in the Mercure de France for July 1729.

The other ‘nouveau Balet Pantomime’ was La Noce Angloise for which the Mercure de France for August 1729 provided a detailed description. This ballet included a singing ‘Sorcière’ with singing ‘camarades’, not long before Roger’s creation of Cephalus and Procris. The report does not name the ballet’s creator but does mention Roger.

‘La figure du Sr. Roger, en Paysan, a été trouvée très originale, & a fait autant de plaisir qu’il en a déja fait en Matelot Hollandais [in the Ballet de l’Amour et de la Jalousie]’

Although his performing career centred on Pierrot (about whom there is much more to say, particularly regarding this character’s appearances on the London stage), Roger did portray other comic characters.

Tragically, Roger’s career was cut short by his sudden death in 1731 in Paris, reported in the Daily Advertiser for 11 November 1731.

I have been aware of Roger since the early days of my research into the life and career of Hester Santlow (later Hester Booth), who danced with and for him during his time at Drury Lane. My work on this short post has highlighted in new ways his significance for the development of stage dancing in early 18th-century London – there is much more to be uncovered about the dances and pantomimes he created at Drury Lane in the late 1720s. Roger was not the only French dancer to pursue a career in London’s theatres and I hope to look at some of the others in future posts.

References:

Jean-Baptiste Dubos, Réflexions critiques sur la poesie et sur la peinture. 4e. éd. 3 vols. (Paris, 1740). Roger is mentioned in volume III, pp. 288-289. I have not been able to check whether he was also mentioned in the previous edition of 1733.

Jean-Baptiste Dubos, translated by Thomas Nugent, Critical reflections on poetry, painting and music. 3 vols. (London, 1748). Roger is mentioned in volume III, p. 219.

Ifan Kyrle Fletcher, ‘Ballet in England, 1660-1740’ in Ifan Kyrle Fletcher, Selma Jeanne Cohen and Roger Lonsdale, Famed for Dance (New York, 1960), 5-20 Roger is mentioned on p. 17.

Philip H. Highfill Jr, Kalman A. Burnim and Edward A. Langhans, A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers … in London, 1660-1800. 16 vols. (Carbondale, 1973-1993). The entry for Roger is in volume 13.

Mercure de France, juillet 1729, p. 1661

Mercure de France, août 1729, p. 1846