Another dance that I have been working on, for the purposes of choreographic analysis, is the ‘Passacaille of Armide by Mrs Elford & Mrs Santlow’ in Anthony L’Abbé’s A New Collection of Dances published around 1725. This was the dance that sparked my interest in Hester Santlow when I first learnt and performed it many years ago. As I returned to it – changing sides (my marked-up notation indicates that I originally danced the left-hand side, probably performed by Mrs Elford) – the choreography began again to cast its spell. It is the most wonderful duet, with so many different aspects.

As I learnt the dance, many technical questions arose in my mind. I was taught three different ways to perform the pas assemblé ending in first position: as a jump from one to two feet ending in plié, much like the modern ballet assemblé; as a jump but landing on the balls of the feet with straight legs and absorbing the impact by lowering through the insteps; and as a form of relevé sauté ending with straight legs and on the balls of the feet. These three versions make different technical demands and are expressive in very different ways that are highly relevant to the passacaille, a dance that – because of its music – is exceptional in its affective range. Among the many notated stage dances I performed, I particularly loved the passacailles.

I have two questions. What evidence is there in the early 18th-century dance treatises for these various modes of performance of the pas assemblé? Where in the Passacaille of Armide duet could the different versions be used?

The pas assemblé is notated by Feuillet in Choregraphie (Paris, 1700) among examples in the main text, within the section entitled ‘De la manière que les Pas se terminent dans les Positions’ (p. 44). It is notated at the foot of the page and called ‘Pas assemblé’ but shown without a jump (or any other marking). In his translation of Feuillet, Orchesography (London, 1706), Weaver shows the same notation but calls it simply ‘a join’d Step’.

The pas assemblé is not described by Rameau in Le Maître à danser (Paris, 1725) but he does include it in his Abbregé de la nouvelle methode dans l’art d’ecrire ou de tracer toutes sortes de danse de ville (Paris, [1725]). Chapter XII of the Abbregé is titled ‘Des Assemblez, Pas de Gaillarde & de Rigaudon’. He describes the step as follows (there is no contemporary or modern translation of this treatise into English):

‘Le Pas Assemblé est un pas plié sur un pied, tandis que l’autre se rapproche en se relevant: si c’est en avant, ce doit être celui de derriere qui vient s’approcher à la premiere position: si c’est en l’arriere, celui de devant se raproche.

Il se pratique de deux manieres; la premiere, en pliant & en se relevant lorsque les deux pieds sont près l’un de l’autre.

Et la deuxieme en sautant: mais la Table de ces Pas est plus demonstrative que toute l’explication que l’on pourroit donner: il s’écrit sur toutes les lignes.

[Abbregé de la nouvelle methode, p. 59. I have not corrected Rameau’s spelling or use of accents]

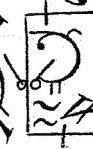

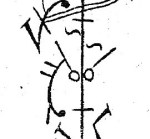

Here is a detail from Rameau’s notations of the pas assemblé:

Kellom Tomlinson devotes chapter XIII of Book the First of The Art of Dancing (London, 1735) to what he calls ‘the Close or Jump’. He begins:

‘What we call a Close in Dancing is, when, the Weight being upon one Foot, we sink, and in the Rise jump or close both Feet equal one to the other, in the first Position, or the Feet are inclosed either before or behind, in the third Position; and this Step generally concludes in the said Positions or Postures. It may be performed in two different Ways, viz. on the Ground, and off from the Ground, as in the Bound;

[The Art of Dancing. Book the First, Chapter XIII, p. 37]

Tomlinson refers to the notated steps he supplies in plates IV and V of Book I as examples, but in this context they are not entirely clear, and I won’t reproduce them here. He also dintinguishes further between ‘a Close on the Ground’ in which the dancer goes ‘no higher than you can rise without quitting the Ground with your Instep or Toe’ (pp. 37-38) and one ‘off from the Ground’ in which:

‘… you sink, in order to spring, as before; but, instead of rising to the Extremity or Point of the Toe, you only spring quite off from the Floor, lighting on both Feet’

He calls this ‘a Close or Jump’ (p. 38). Tomlinson also provides some interesting information relating to the timing of the step:

‘This Step in Dancing much resembles a Period or full Stop in Letters; for, as that closes or shuts up a Sentence, the Close in Dancing does the very same in Music, since nothing is more frequent than, at the End of a Strain in the Tune, to find the Strain or Couplet of the Dance to conclude in this Step, as also at other remarkable Places of the Music. (p. 39)

He adds ‘This Step generally takes up a Measure, that is to say, with the Time you rest or stand still’ (p. 39).

Between them, the descriptions in the various dance manuals indicate different versions of the pas assemblé, providing evidence for the versions I was taught.

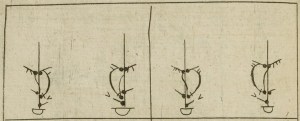

Returning to L’Abbé’s ‘Passacaille of Armide’, the pas assemblé occurs on its own in six bars (37, 53, 77, 81, 117, 141) each time as a new variation begins in the music. All are notated with a jump, but no plié at the end of the step. Here are the notations for each of them, as notated for the dancer who begins on the right, but performs much of the dance on the left side.

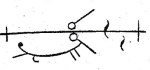

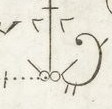

As you can see, the first two have a quarter-turn on the jump and all but one end facing downstage (in bar 53 the dancers face one another across the stage). Bar 81 is really a jump from second to first position rather than a pas assemblé. There is a seventh pas assemblé (bar 101), which incorporates a beat and also ends facing downstage. Here is the notation showing the two dancers side by side.

In addition, there are another five pas assemblés which form part of pas composés (Bars 61, 85, 93, 98, 144). I won’t include the notations here, but the pas assemblé begins most of these steps and some end in plié while others don’t. My interest is in the moment of stillness following the single pas assemblés, so I will not pursue these.

When I began to explore this particular step within L’Abbé’s choreography to the passacaille in Armide, I was looking for ways in which it might enhance the variety and intensify the drama of the duet. I expected to find bars where the stronger dynamic of a relevé sauté might be used instead of a close on straight legs – which might be soft or sharp – given that all the examples I list are notated with a jump and without a plié. However, after listening to three different recordings of the music I began to question this idea. L’Abbé’s choreography is complex, with many small jumps and much ornamentation (turns, slides, falls and beats) within the pas composés. In each of the recordings none of the bars concerned emphasise the end of the variation, minimising the effect of the the dancers’ stillness during beats 2 and 3.

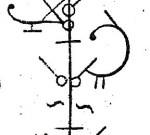

I turned to Pecour’s choreography ‘Passacaille pour une femme dancée par Mlle Subligny en Angleterre de Lopera darmide’ – an obvious point of reference, as she probably danced it in London in 1702 while L’Abbé’s choreography may well date to 1706 – to see how he treated the same bars in the music. Of the seven instances I focus on, Pecour has a simple pas assemblé in only two (bars 37 and 141). In bar 101, where L’Abbé has an assemblé battu, Pecour uses the same step as the first element of a pas composé. Here are Pecour’s steps in notation:

What should I make of this? One obvious thought is that the pas assemblé does not mark a full stop either in the dance or in the music. It is, perhaps, closer to a pause with a breath before the dancers and the music continue. I am not musically trained in any way and there will doubtless be very different ideas among those who are.

The interpretations in the three recordings returned me to the livret and the dramatic context within which the passacaille is played. It opens act 5 scene 2 of Lully’s Armide and is woven throughout the scene. Armide has left Renaud alone while she visits the underworld for demonic advice. She uses her magic powers and:

‘Les Plaisirs et une troupe d’Amants fortunés et d’Amantes heureuses viennent divertir Renaud par des chants et par des danses.’ [Quinault, Livrets d’Opéra, vol. 2, p. 282]

This is a pastoral scene, ostensibly devoted to love and pleasure. When I first learnt the duet and explored its operatic context, I was struck by the idea these Pleasures and Happy Lovers were demons in disguise, and this has continued to colour my understanding and interpretation of L’Abbé’s choreography. Yet, as I returned to it and tried to look a little closer, I realised that this demonic aspect is carefully hidden. If it appears at all, it is only occasionally and momentarily. And, of course, there are the underlying questions of L’Abbé’s intentions in creating a duet for the London stage where it would have lacked its original operatic context, and what Mrs Elford and Miss Santlow may have been able to express when performing it.

As with all of these notated dances, there are more questions than answers, and great variety of choices when it comes to reconstructing L’Abbé’s ‘Passacaille of Armide’ duet whether for research or performance.

Further Reading:

Moira Goff, The Incomparable Hester Santlow (Aldershot, 2007), pp. 7-9

Rebecca Harris-Warrick, Dance and Drama in French Baroque Opera (Cambridge, 2016)

Philippe Quinault, Livrets d’Opéra présentés et annotés par Buford Norman. 2 vols. (Toulouse, 1999), Vol. 2, 249-287, ‘Armide’.

Judith L. Schwartz, ‘The passacaille in Lully’s Armide: phrase structure in the choreography and the music’, Early Music, XXVI.2 (May 1998), 301-320.

Three recordings of the Passacaille d’Armide:

Lully, Divertissements. Capriccio Stravagante, Skip Sempé. 15. Passacaille d’Armide (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, 1990)

Lully, Armide. Choeur et Orchestre du Collegium Vocale et de la Chapelle Royale, Dir. Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi, 1993)

Lully, Les Divertissements de Versailles. William Christie, Les Arts Florissants. 14. Act 5 scene 2 (Erato, 2002)